176 ?<► SHADY CHARACTERS

THE MANICULE 177

рч«- Л.ІГ ми^ѵ

AI*T‘A "xriW-vV.li гм^ѴІЧі* I

Vf- • -t1 tVfvirtV- • /.

^gbûVf- pfWWUf*

vKxwiiy «*-

^ИО CUIgìLlUcft* fUZCTtrPBin ’V7JT l\ Т_А I'. «„

<** «4 / «-«ре »«ывк ífeh пл0сс ■ л“г ™ " •

лс «mczrt,« кто ™mw •™ f“* ;

■nei» тяплгі5. ur«rw дЬЬ .a- f.tëttr ? .1 W

db libi» îrnubczc ïghotn-тѵ

fxmwr

^Чи-урлц,*-

«nopr^Turtn^-- «fcc Т^вЛЙпГ*

. <««* ™ІріЛл.ГЛс^!т« •!

) w- «1 -V °=b'n imi игктл tc fmmy fiais TO.uijaiKînilp.îm|i:

№ * rc шпппс^г „m., -n+U

цкУт iteflcicftpraTmc югс Tir, namni. <*Т*-л —

libitonc* iSqufU- fe. ni ?tcç (|¡ 7* ii> fcc uno icnciur, fr аші?

liartcwj; я<|ndtHT11ІИШІ rio Iifuc 1» нет* тлО neri

riGi/bfijbc^xiïiipn-nerum miri) uru^ fieu pib. .frft m

>uifm7ii4 (ìt--fUtiiv-tirn£G. « coefh fcfcifù, П ni Iinuf. «ra

Ті оГпсппс (hrnfiT" тплісй Гетр НТ1Я сП- с.тхтт). .jet«,

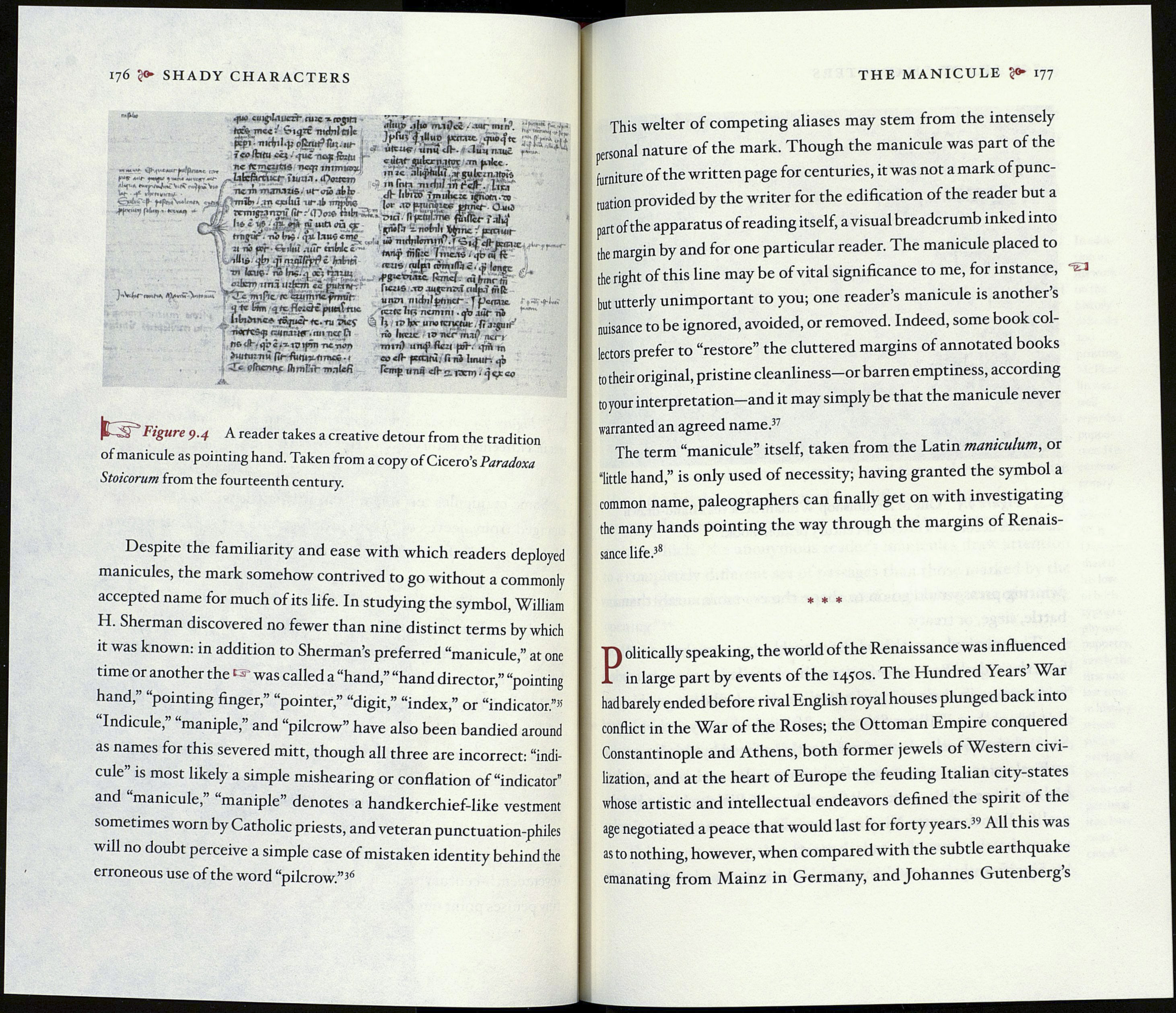

çure 9.4 A reader takes a creative detour from the tradition

of manicule as pointing hand. Taken from a copy of Cicero’s Paradoxa

Stoicorum from the fourteenth century.

Despite the familiarity and ease with which readers deployed

manicules, the mark somehow contrived to go without a commonly

accepted name for much of its life. In studying the symbol, William

H. Sherman discovered no fewer than nine distinct terms by which

it was known: in addition to Sherman’s preferred “manicule,” at one

time or another the ra* was called a “hand,” “hand director,” “pointing

hand,” “pointing finger,” “pointer,” “digit,” “index,” or “indicator.”«

Indicule, maniple, and pilcrow” have also been bandied around

as names for this severed mitt, though all three are incorrect: “indi¬

cule” is most likely a simple mishearing or conflation of “indicator”

and “manicule,” “maniple” denotes a handkerchief-like vestment

sometimes worn by Catholic priests, and veteran punctuation-philes

will no doubt perceive a simple case of mistaken identity behind the

erroneous use of the word “pilcrow.”36

This welter of competing aliases may stem from the intensely

personal nature of the mark. Though the manicule was part of the

furniture of the written page for centuries, it was not a mark of punc¬

tuation provided by the writer for the edification of the reader but a

part of the apparatus of reading itself, a visual breadcrumb inked into

the margin by and for one particular reader. The manicule placed to

the right of this line may be of vital significance to me, for instance, ' ¿ a

but utterly unimportant to you; one reader’s manicule is another’s

nuisance to be ignored, avoided, or removed. Indeed, some book col¬

lectors prefer to “restore” the cluttered margins of annotated books

to their original, pristine cleanliness-or barren emptiness, according

toyourinterpretation-and it may simply be that the manicule never

warranted an agreed name.37

The term “manicule” itself, taken from the Latin maniculum, or

“little hand,” is only used of necessity; having granted the symbol a

common name, paleographers can finally get on with investigating

the many hands pointing the way through the margins of Renais¬

sance life.38

* * *

Politically speaking, the world of the Renaissance was influenced

in large part by events of the 1450s. The Hundred Years War

had barely ended before rival English royal houses plunged back into

conflict in the War of the Roses; the Ottoman Empire conquered

Constantinople and Athens, both former jewels of Western civi¬

lization, and at the heart of Europe the feuding Italian city-states

whose artistic and intellectual endeavors defined the spirit of the

age negotiated a peace that would last for forty years.39 All this was

as to nothing, however, when compared with the subtle earthquake

emanating from Mainz in Germany, and Johannes Gutenberg s