172 SHADY CHARACTERS

more realistic suggestion.1? He opined that the conscientious reader

should “observe occurrences of striking words, archaic or novel dic¬

tion, cleverly contrived orwell adapted arguments, brilliant flashes

of style, adages, example, and pithy remarks worth memorizing,” and

that such passages should be marked by an appropriate little sign.”'®

Erasmus left the choice of this “appropriate little sign” to his readers

and overwhelmingly, they chose the manicule.

* * *

T T nlike the pilcrow, which wended its way from К for kaput to the

VJ more familiar f over a millennium, or the octothorpe, which

metamorphosed from “lb” to 1Ѣ and then #, the manicule’s bluntly

representational form has remained nearly unchanged since its earli¬

est reported instances. Once, there were no manicules; then, spring¬

ing fully formed into existence, there they were.

The earliest attested manicules appeared in the Domesday Book,

the exhaustive survey of England carried out for William I in 1086.”

The “Winchester Roll” or “King’s Roll,” as it was called at first, was

intended to be an authoritative record of land ownership-а “dooms¬

day” judgment from whichno deviation would be brooked, occasioning

the book’s later nickname.20 Frustratingly, the only direct reference to

the manicules used in this nine-hundred-year-old document is a brief

aside in a rambling 1824 treatise on the art of Typographia. Its author,

John Johnson, lists ” (no name is given) alongside other “marginal

references” such as the Maltese cross (*), the ancient Greek asteris-

( • ), the dagger (f), and a bevy of apparently abstract geometric

symbols, then dismissively writes that these inscrutable marks “in

most instances explain themselves.”2’ He says no more on the subject.

The manicule next surfaced in the twelfth century, though solid

facts about its use in this period are thin. Geoffrey Ashall Glaister’s

comprehensive Encyclopedia of the Book describes the symbol as the

THE MANICULE У* 173

“digit,” and alleges that it was “found in early twelfth century (Span¬

ish) manuscripts.”22 As with Johnson’s dismissal of the Domesday

Book’s “self-explanatory” reference marks, Glaister’s factoid is dashed

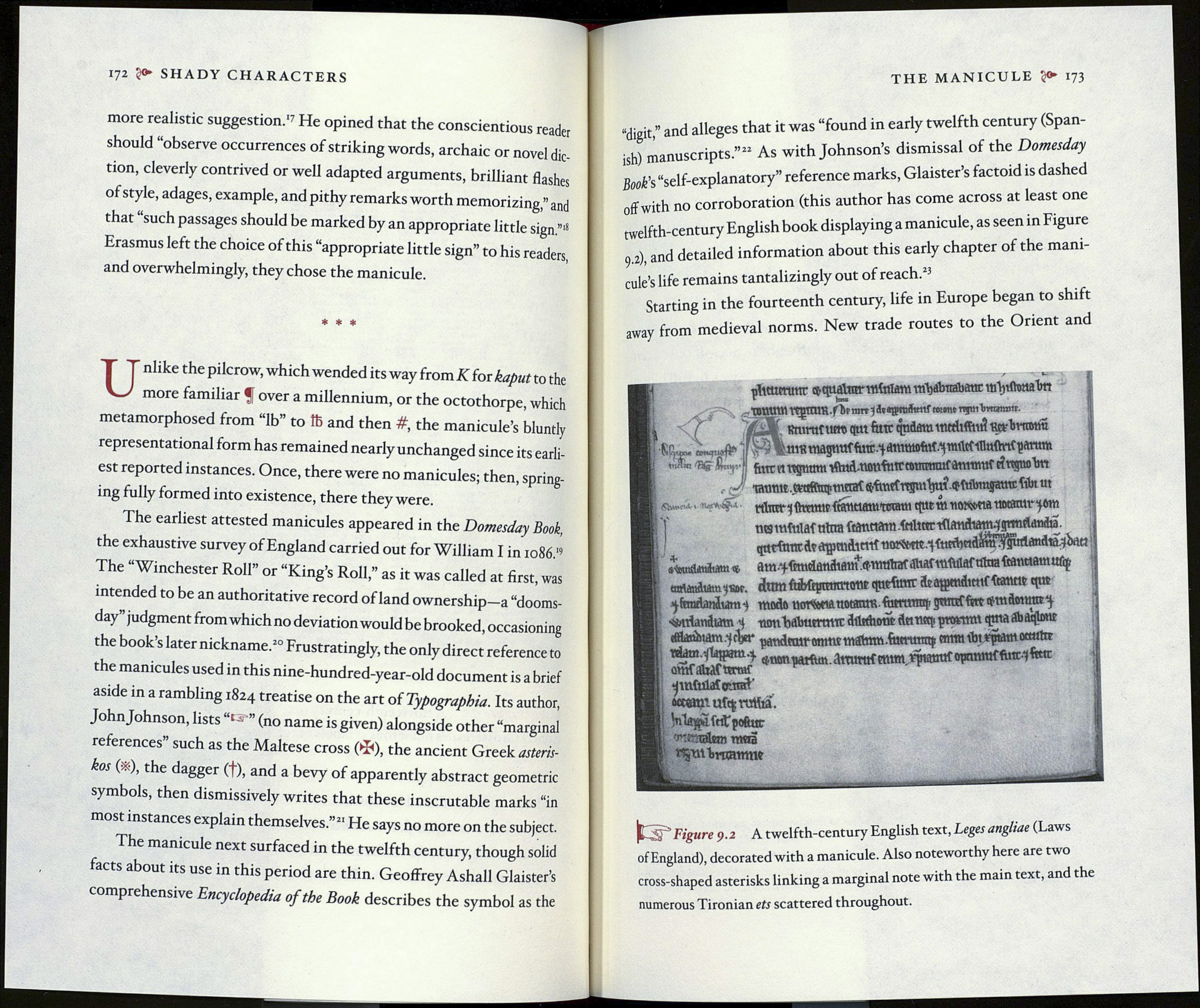

off with no corroboration (this author has come across at least one

twelfth-century English book displaying a manicule, as seen in Figure

9.2), and detailed information about this early chapter of the mani¬

cule’s life remains tantalizingly out of reach.23

Starting in the fourteenth century, life in Europe began to shift

away from medieval norms. New trade routes to the Orient and

'S»

Í Sbwni-' -ПіЛ-фл

«•SemfliiAam ч

çhmmrnr $ qualmt mtnUm vnbabttatettt mlnftratabti

■nmmtl Ytjmm.fJlprnTT'jfoaffniiitttr ГС»™ rtyii Imam™.

¿Эг Knmt futro qm httt qudam mtdifftu! «crbmmu

ma mgtmf fivtr .3 atvmtofuf .4 ttultf iThtftnf p лшт

fitte »t ttguum tftitd-nottfmr mtimraif àttrmuf fittgnolm

latmtt .tvtfftartnetaf qffmrf itgtulju?

tus miniai ultra ftónctam Миге iilftndiatn4gm«ldnd¿.

qurftmt dt ¿rçpmdintf uoNitttd ítttthnd™TgttrtcWdtayh.io

am^feudûndtattt'Æunflraf Æltaf tufiilaf titra fiattetam ufip

turtattàtâm^sor. dam fttbûptnnoi» qtudtmt dtagiuidttttf tanttt qut

^ftmdatiluttf) modo ttot4

rdam.^tajpam.y ^. dttuntf mtm rptaW opmintf ftitr-1fett

atttTaUACttmf ^

^тСиІаГоотІ’

W. ufq rutó.

inlagSftifpofiur

weraStm tura

«stiibruatmit

Figure 9.2 A twelfth-century English text, Leges angliae (Laws

of England), decorated with a manicule. Also noteworthy here are two

-shaped asterisks linking a marginal note with the main text, and the

cross

numerous Tironian ets scattered throughout.