»

Chapter ÇI ^ The Manicule

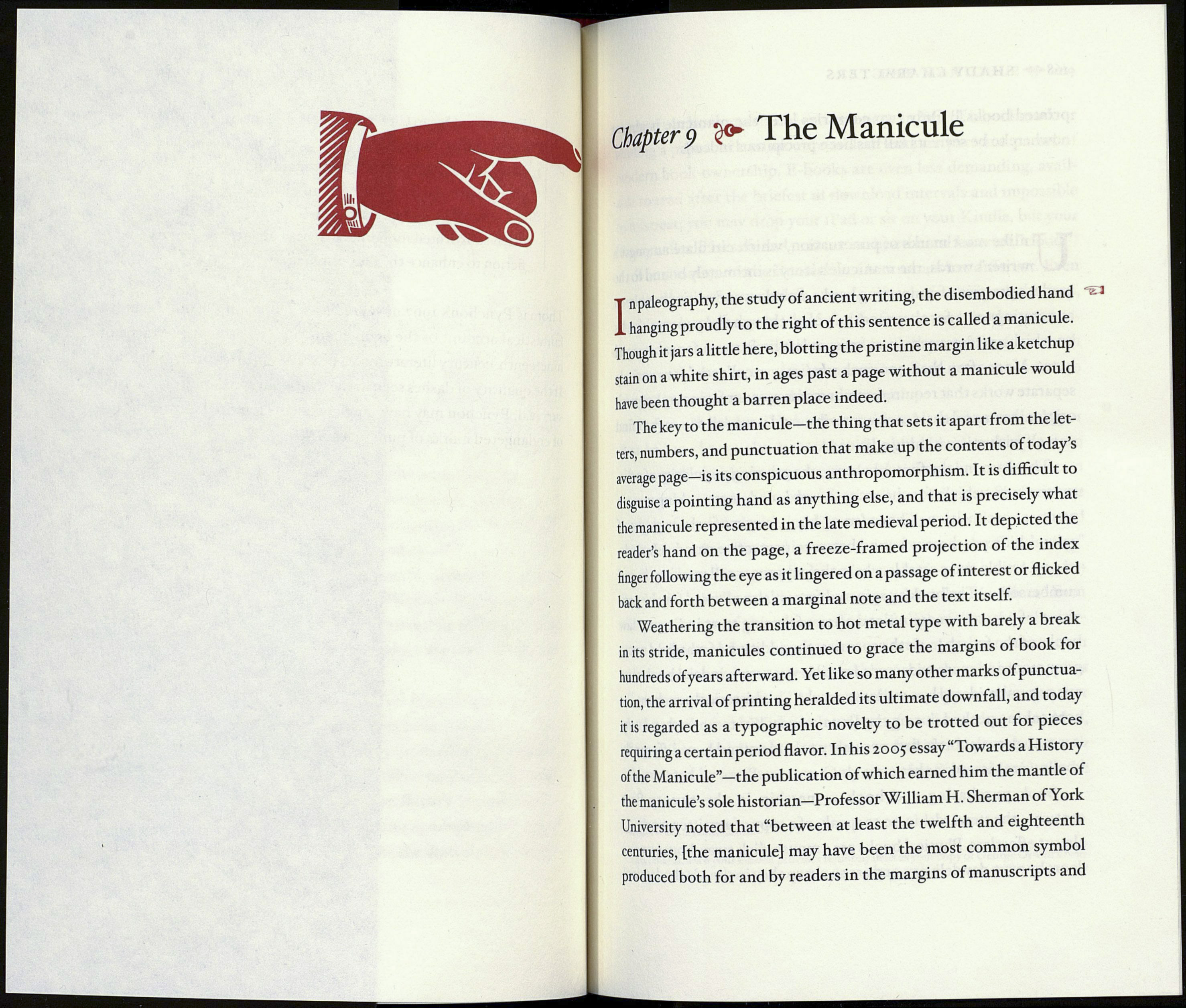

In paleography, the study of ancient writing, the disembodied hand

hanging proudly to the right of this sentence is called a manicule.

Though it jars a little here, blotting the pristine margin like a ketchup

stain on a white shirt, in ages past a page without a manicule would

have been thought a barren place indeed.

The key to the manicule—the thing that sets it apart from the let¬

ters, numbers, and punctuation that make up the contents of today’s

average page-is its conspicuous anthropomorphism. It is difficult to

disguise a pointing hand as anything else, and that is precisely what

the manicule represented in the late medieval period. It depicted the

reader’s hand on the page, a freeze-framed projection of the index

finger following the eye as it lingered on a passage of interest or flicked

back and forth between a marginal note and the text itself.

Weathering the transition to hot metal type with barely a break

in its stride, manicules continued to grace the margins of book for

hundreds of years afterward. Yet like so many other marks of punctua¬

tion, the arrival of printing heralded its ultimate downfall, and today

it is regarded as a typographic novelty to be trotted out for pieces

requiring a certain period flavor. In his 2005 essay Towards a History

of the Manicule”—the publication ofwhich earned him the mantle of

the manicule’s sole historian—Professor William H. Sherman of York

University noted that “between at least the twelfth and eighteenth

centuries, [the manicule] may have been the most common symbol

produced both for and by readers in the margins of manuscripts and