іб2 30* SHADY CHARACTERS

t-Âf5 Figure 8.4 An illustration of an early QWERTY keyboard taken

from Sholes’s 1878 patent, with the hyphen-minus character third from

the right on the top row. The dashlike character at top-right is actually an

underscore.70

Still, though, typists adapted. Even before the nineteenth cen¬

tury was out, Isaac Pitman, inventor of Pitman shorthand, proponent

of phonetic spelling, and a steadfastly unsentimental sort of chap,

declared that a single, spaced hyphen - or preferably, two unspaced

hyphens—would serve perfectly well in place of the absent em dash.''

The practice was not universally admired: the dime novelist William

Wallace Cook was one early voice of protest, writing in 1912 that he

considered it “poor policy” to be forced into using two hyphens where

an em dash should rightly be placed.72

Despite Cook’s misgivings, Pitman’s shortcut was persistent. The

double hyphen became a familiar sight in typewritten documents,

and though printers could still call upon a full complement of dashes,

the occasional double hyphen sometimes slipped past an inattentive

compositor to end up in print.73 In one particular niche, the — suc¬

ceeded in displacing even handwritten dashes; among its many con¬

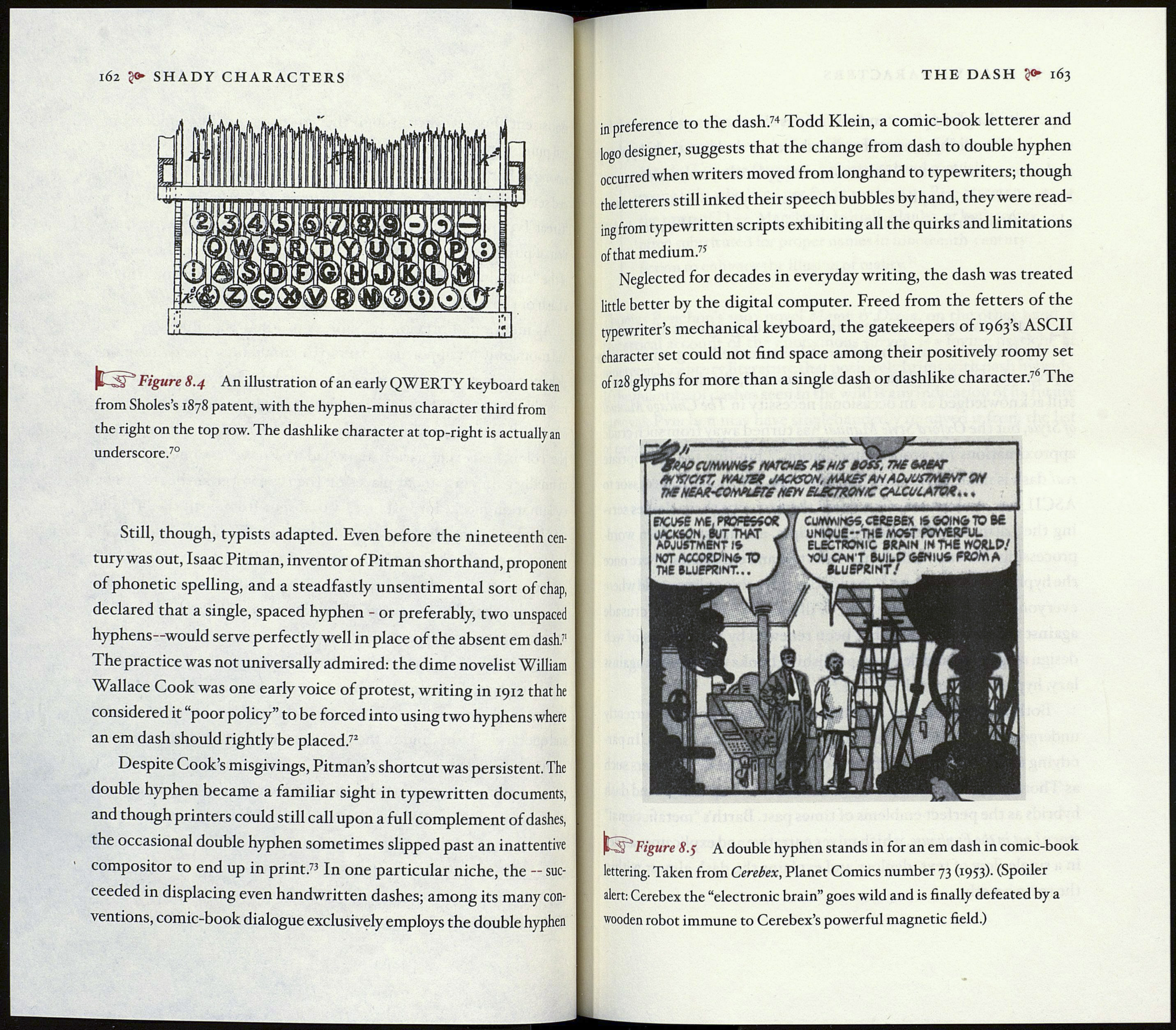

ventions, comic-book dialogue exclusively employs the double hyphen

THE DASH 3^ 163

in preference to the dash.74 Todd Klein, a comic-book letterer and

logo designer, suggests that the change from dash to double hyphen

occurred when writers moved from longhand to typewriters; though

theletterers still inked their speech bubbles by hand, they were read¬

ing from typewritten scripts exhibiting all the quirks and limitations

ofthat medium.75

Neglected for decades in everyday writing, the dash was treated

little better by the digital computer. Freed from the fetters of the

typewriter’s mechanical keyboard, the gatekeepers of 1963’s ASCII

character set could not find space among their positively roomy set

of 128 glyphs for more than a single dash or dashlike character.76 The

cé?jr

CVtMUN&f NATCNSS NSN/Í tots, TH£ MtV

ANIf/OfT, WAITS* JACKSON, MAKSS AH AOJUSTNW ON

THS N£M<0MPt£rS NSW EL8CT*0N/C CALCUIATVA..,

Cummings, ceresex « going to B£

UNK?ue--TH6 MOST POWERFUL

ELECTRONIC »RNN IN THE WORLD/

>0U CAN'T MILD GENIUS FROM A

V RLUEPRlNT/ ^

EXCUSE ME, PtüfESSOR

JXCK4ÖN, BUT THAT ,

APJUSTMENT IS X

NOT ACCORDING TO 1

THE BLUEPRINT... J

(G11 Figure 8.5 A double hyphen stands in for an em dash in comic-book

lettering. Taken from Cerebex, Planet Comics number 73 (1953). (Spoiler

alert: Cerebex the “electronic brain” goes wild and is finally defeated by a

wooden robot immune to Cerebex’s powerful magnetic field.)