148 3» SHADY CHARACTERS

¿¡Га“9' у-У $ fôyjf>eS~\uô

■ttsdibeB& SU& dit,yU&P ілл\*м£<ХГАЛ

Auà«a$*i y* ^

pfypy/r jui 02%^^

ju. (fce&gpt) \¿zfon ôÿy унфЪ> Jtuô- CIH«¿| tu W,

JUl* 0+ч.*иЯ j

Л И0-.; A

JVÍÍ y& pli&ßn.itf'jR ч& civn.<-«9 Луі>иу%? tjsxy Ли8

yAuö í)¿4l., ^)Л-Ну^4» / JiitPfcoyfëK+ V^/ lCtS! jìfaQj

ÉjyvM e-Qtty^~

&ydr y* y abàfî сЪт\Ь*& ^ѵѵ t ou/ЬѵH-ryui

|)'-Ѳ0л<^^

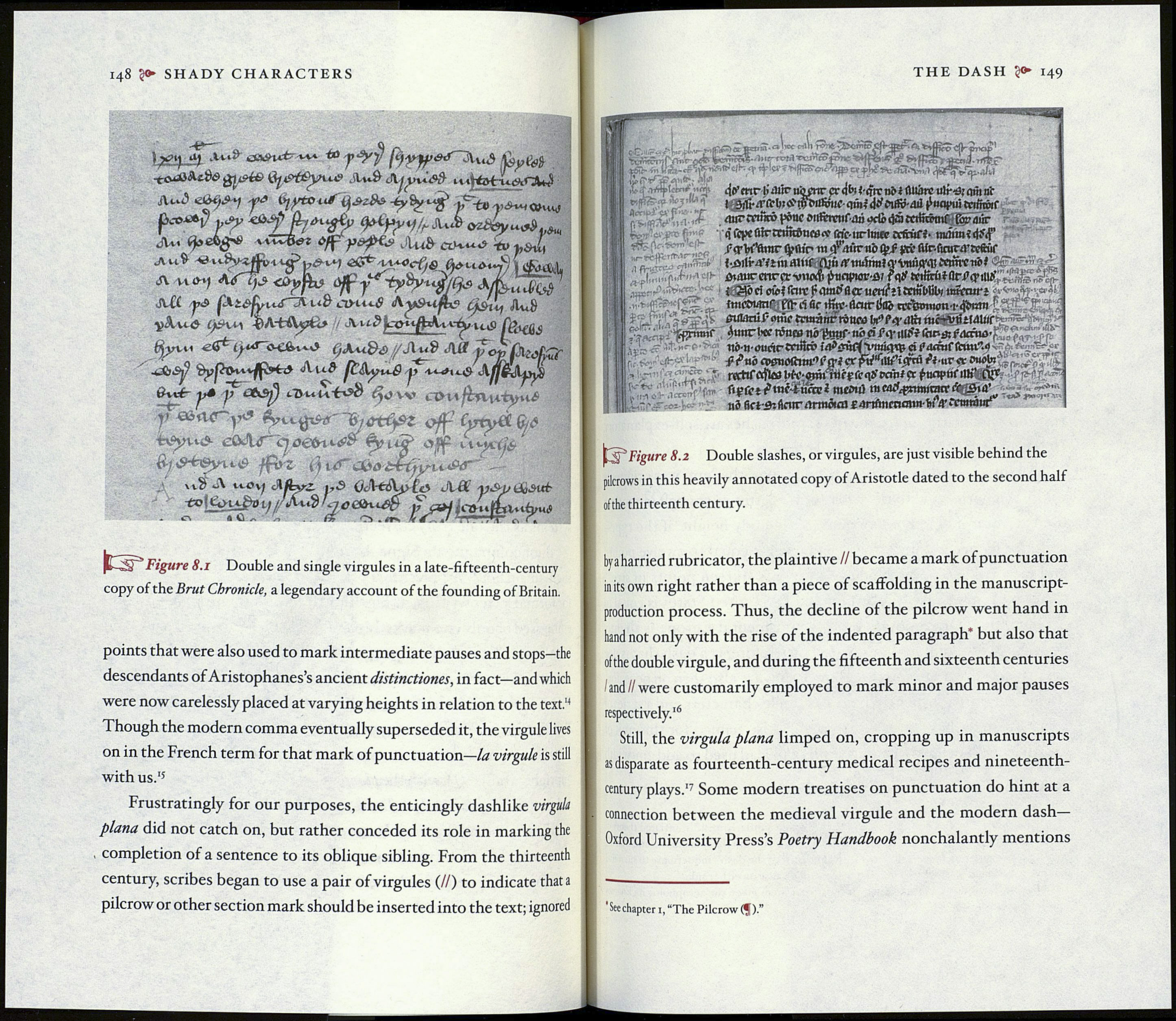

Я)&Ь&уіі,ф ffbz (j i мЭ J\ K.C4J cHApr¿- и«S OcA-e¿Vp Co Jiff -y Figure 8.1 Double and single virgules in a late-fifteenth-century points that were also used to mark intermediate pauses and stops—the Frustratingly for our purposes, the enticingly dashlike virgule THE DASH 3»- 149 я fins«® V; СЪ ^ШгР cip П.И.-Ч* - 'V 'V, , .„.п. V,t .Tt ('ÍÜ'.'V,l ) ifO’crir l¡ Л1ІГ ubctir a db <- övwrmrorviwfj |Уипрмг-А( fqÿ йЩосіowl(hitfmntfflttlwtfîltniTMito înîrturi T r¿ »Mir ігюапггоммія ге4'м1пімс^И£І«ШГ^т*2,*??ѵ: ífirimir ^unrt«i^cBndT^-nóo'fiyiWfí(hn*>atnu>Y „*¡£04* /- A. - J. wîioOTP*! h.i — »tV'tl’VUVIi v^Uiiv |*Г"‘НД VI j S i' J ' r\ . '.(f-- ffub еош#ті>е<»і<хУ&(л('ія*Ь Л*«г fr л«*»-', - . r rwttfftjl^WV'emThfçftqÿtwitp:¿twpttf itófenj* i^r ~ '’T V ì'’p fiyürt^tfli-ïuctci mtínil mMApnmttatrdígSiú’^ Figure 8.2 Double slashes, or virgules, are just visible behind the bya harried rubricator, the plaintive // became a mark of punctuation Still, the virgula plana limped on, cropping up in manuscripts 'Sec chapter 1, “The Pilcrow (J).”

copy of the Brwi Chronicle, a legendary account of the founding of Britain.

descendants of Aristophanes’s ancient distinctiones, in fact—and which

were now carelessly placed at varying heights in relation to the text.4

Though the modern comma eventually superseded it, the virgule lives

on in the French term for that mark of punctuation—la virgule is still

with us.15

plana did not catch on, but rather conceded its role in marking the

, completion of a sentence to its oblique sibling. From the thirteenth

century, scribes began to use a pair of virgules (//) to indicate that a

pilcrow or other section mark should be inserted into the text; ignored

qfcpcnírmmStioare nfc-tirlmfe cvftüri- mmm?4&F

ÿ

nä (ift'âidnir annoiai rartfitictimm-ttíVrcmtíitir'

pilcrows in this heavily annotated copy of Aristotle dated to the second half

ofthe thirteenth century.

in its own right rather than a piece of scaffolding in the manuscript-

production process. Thus, the decline of the pilcrow went hand in

hand not only with the rise of the indented paragraph’ but also that

ofthe double virgule, and during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries

I and II were customarily employed to mark minor and major pauses

respectively.16

as disparate as fourteenth-century medical recipes and nineteenth-

century plays.'7 Some modern treatises on punctuation do hint at a

connection between the medieval virgule and the modern dash—

Oxford University Press’s Poetry Handbook nonchalantly mentions