140 SHADY CHARACTERS

on the composing stick to adjust H&J over a few lines at a time, with

the processing power of a computer behind it, TpX could try every

possible paragraph layout* in the search for the best overall combina¬

tion of word spacing, letter spacing, and hyphenation.61 In order to

compute the optimal paragraph layout, each decision made in setting

a given text was assigned a “badness” score: marginal hyphens were

bad, successive marginal hyphens worse; word and letter spaces were

allowed to vary within a small range of values but excessive adjust¬

ment carried a penalty. Breaking of phrases that should normally be

kept together (such as proper names and mathematical formulae) was

penalized, as were widows and orphans (single lines left behind or

carried over to a new page).62

Essentially, Knuth programmed TeX with knowledge of the

same aesthetic decision-making process that a typographer would

carry out; unlike that typographer, TeX could perform thousands of

paragraph arrangements every second and pick the best among them.

Knuth’s optimistic experiment in typesetting had moved typography

a step closer to Hermann ZapPs tantalizing “perfect grey type area.”

Hermann Zapf himself raised the bar even further in the mid-

1990s with the aid of a little shoulder-standing. Publishing a paper

touting the benefits of his self-referentially named “hz- program,” Zapf

took TeX s paragraph-justification mechanism to extraordinary new

lengths.

Even a very short paragraph with ten possible line-break locations, including spaces between

words, inter-word hyphens, and optional “soft” hyphenation points, can be arranged in 1,024

distinct ways. TgX, however, ignores some obviously unlikely cases (such as placing one word

on the first line and all the rest on the second, and so forth); this, along with some clever

computational tricks, reduces the typical number of configurations to be tested to around the

same as the number of potential break points.60 Adding in other parameters, however, such

as word spacing and letter spacing, the permitted length of a paragraph’s final line, and so on,

redoubles the complexity of the problem.

THE HYPHEN 141

There now is your insu¬

lar city of the Manhattoes

belted round by wharves as

Indian isles by coral reefs—

commerce surrounds it with

her surf. Right and left

the streets take you water-

war d. Its extreme downtown

is the battery, where that no¬

ble mole is washed by waves

and cooled by breezes, which

a few hours previous were

out of sight of land. Look at

the crowds of water-gazers

there.

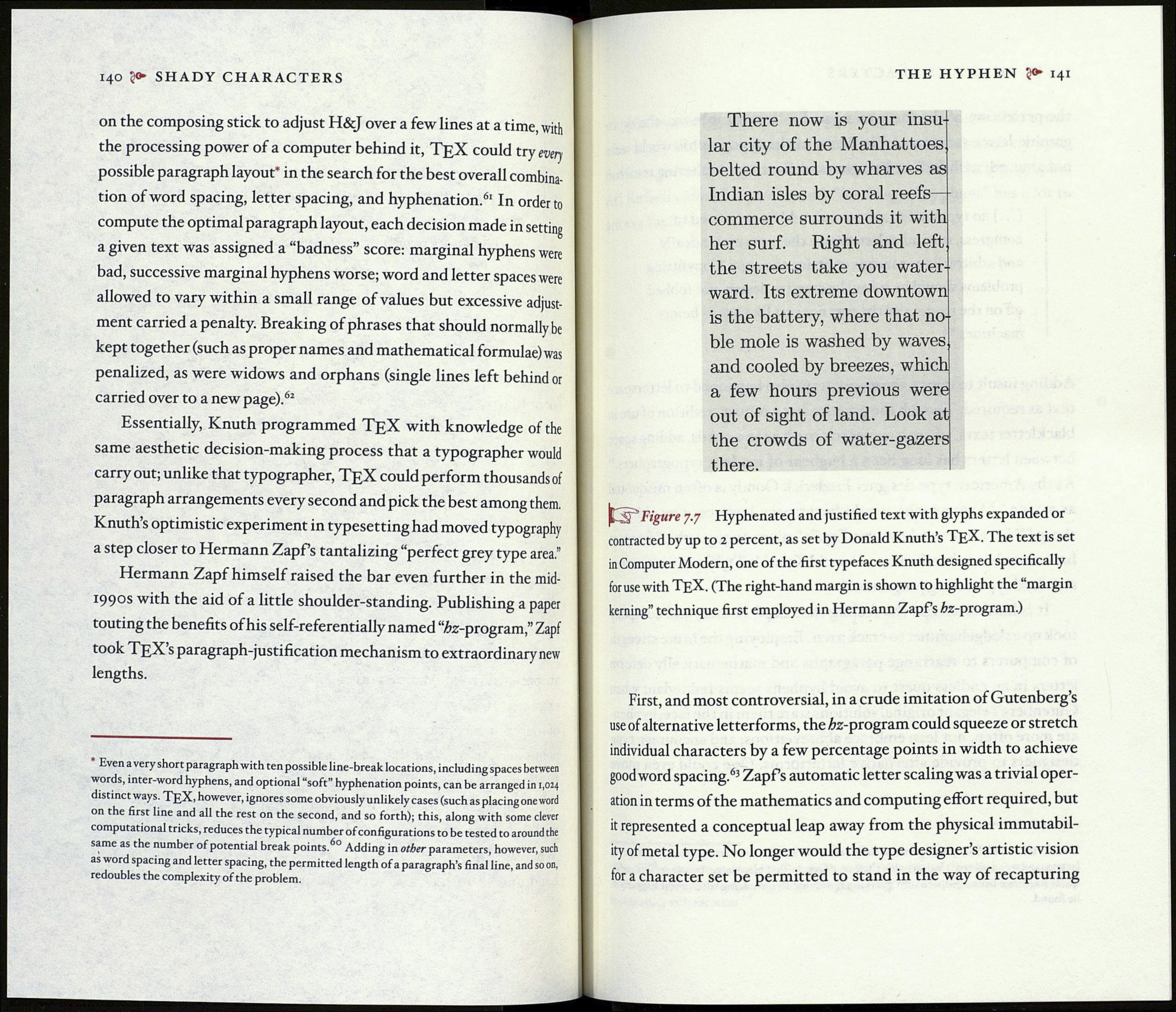

Figure 7.7 Hyphenated and justified text with glyphs expanded or

contracted by up to 2 percent, as set by Donald Knuth’s TeX. The text is set

in Computer Modern, one of the first typefaces Knuth designed specifically

foruse with TeX. (The right-hand margin is shown to highlight the “margin

kerning” technique first employed in Hermann ZapPs fe-program.)

First, and most controversial, in a crude imitation of Gutenberg’s

use of alternative letterforms, the ¿z-program could squeeze or stretch

individual characters by a few percentage points in width to achieve

good word spacing.63 ZapPs automatic letter scalingwas a trivial oper¬

ation in terms of the mathematics and computing effort required, but

it represented a conceptual leap away from the physical immutabil¬

ity of metal type. No longer would the type designer’s artistic vision

for a character set be permitted to stand in the way of recapturing