134 V* SHADY CHARACTERS

device would never get drunk, would work as diligently at three a.m

as three p.m., and was immune to unionization.40 Unfortunately, for

all his foresight, Clemens invested his faith—and his money-in the

wrong man. James W. Paige fiddled in vain with the intricate and

flawed “Paige typesetter” for a fruitless decade, bankrupting his

sponsor even as they were overtaken by events outside their control.«'

First, in 1886 an immigrant German watchmaker named Ottmar

Mergenthaler demonstrated his line-casting “Linotype” machine to

an audience of delighted newspapermen, whereas Tolbert Lanston's

“Monotype” system, unveiled a few years later, was similarly well

received in the fine printing world of bookmaking.42 The Linotype

and Monotype may have lacked the novelty of Jacquard’s loom or the

legendary complexity of Babbage’s difference engine, but their com¬

bined impact on the printing industry was earthshaking.

Mergenthaler’s Linotype machine, the first to appear by a few

years, was a ticking, whirring behemoth. So named because it pro¬

duced a “line o’ type” at a time, the Linotype combined composition,

casting, and distribution (the tedious process whereby a compositor

returned each letter to its appropriate compartment in the type case)

into a single machine.43 As an operator typed at the Linotype’s key¬

board, brass matrices carrying engraved characters were released from

an overhead magazine and assembled into a line along with wedge-

shaped spacebands.” Next, the automated justification system forced

these spacebands simultaneously upward, widening the line until it

abutted the ends of the desired column measure. From there, a molten

alloy of lead, antimony, and tin was forced into the mold formed by

the justified line to create a “slug,” or line of type.44

Though the Linotype’s automatic justification mechanism freed

compositors from the laborious process of spacing and respacing

lines, it was not without drawbacks. Other than the plaintive ringoia

hyphen bell rigged to sound as the line neared completion, deciding

where a line ended or when a word should be hyphenated remained a

THE HYPHEN 133

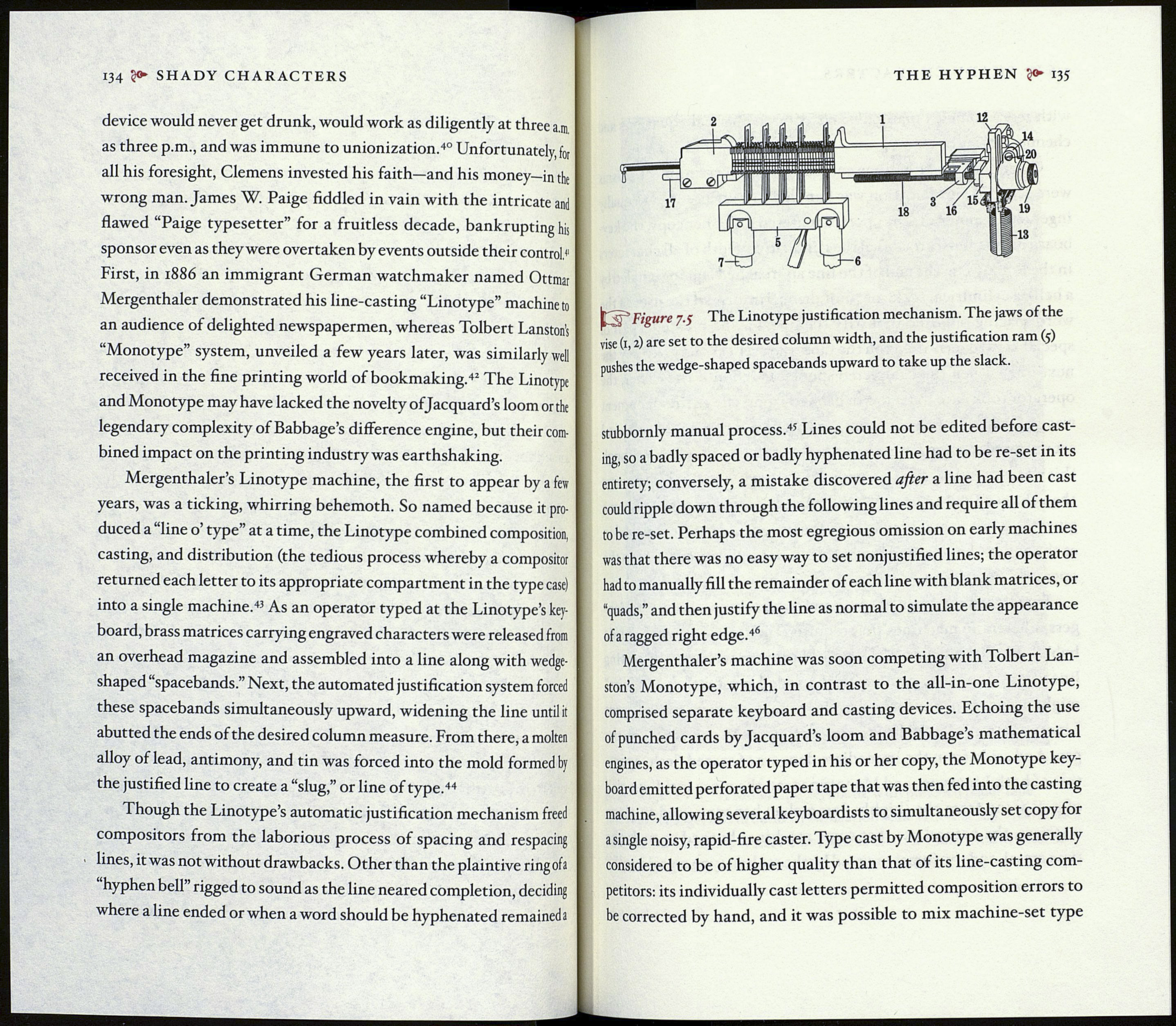

Figure 7.3 The Linotype justification mechanism. The jaws of the

vise (1,2) are set to the desired column width, and the justification ram (3)

pushes the wedge-shaped spacebands upward to take up the slack.

stubbornly manual process.45 Lines could not be edited before cast¬

ing, so a badly spaced or badly hyphenated line had to be re-set in its

entirety; conversely, a mistake discovered after a line had been cast

could ripple down through the following lines and require all of them

tobe re-set. Perhaps the most egregious omission on early machines

was that there was no easy way to set nonjustified lines; the operator

had to manually fill the remainder of each line with blank matrices, or

“quads,” and then justify the line as normal to simulate the appearance

of a ragged right edge.46

Mergenthaler’s machine was soon competing with Tolbert Lan-

ston’s Monotype, which, in contrast to the all-in-one Linotype,

comprised separate keyboard and casting devices. Echoing the use

of punched cards by Jacquard’s loom and Babbage’s mathematical

engines, as the operator typed in his or her copy, the Monotype key¬

board emitted perforated paper tape that was then fed into the casting

machine, allowing several keyboardists to simultaneously set copy for

a single noisy, rapid-fire caster. Type cast by Monotype was generally

considered to be of higher quality than that of its line-casting com¬

petitors: its individually cast letters permitted composition errors to

be corrected by hand, and it was possible to mix machine-set type