122 ?<► SHADY CHARACTERS

The hyphen was first documented by another in the longlint

of overachieving, tax-evading scholars at the library of Alex¬

andria. With punctuation already invented, the Earth’s diameter

measured, and Homer’s epic poetry saved for future generations, the

second-century-BC grammarian Dionysius Thrax was evidently left

with precious little to do.* A student of the fifth librarian Aristarchus

(he of asterisk and obelus fame), Thrax set to work on a short essay

entitled “Tékhnë Grammatiké,”t or the “Art of Grammar,” document¬

ing the state of the art in grammatical practice.3 The Tékhnë con¬

cerns itself largely with morphology, or the construction of words,

digressing briefly on the high, middle, and low points first created

by Aristarchus’s predecessor, Aristophanes, and in later supplements

strays further into punctuation and other matters.4 Though some of

the scribal practices Thrax described were employed patchily at best,

the Tékhnë remains both the earliest known and the most important

work on the ancient Greek language.

The first of Thrax’s supplements addressed prosody, or the spoken

delivery of a text, and catalogued the marks used to clarify the empha¬

sis, intonation, and rhythms therein.5 Nestled between the familiar

apostrophe ( ), which clarified ambiguous syllable boundaries, and

the commalike hypodiastole (3), used to separate difficult words, lay the

hyphen (.—.) a bowed line drawn under adjacent words to indicate

that they should be understood as a single entity.6 In an age when texts

were written entirely without word spaces, the hyphen, apostrophe,

and hypodiastole were invaluable in interpreting an author’s words.

The conjoined words ‘littleusedbook,” for example, are given quite

* For more on the Alexandrian library and its laundry list of achievements see chapter 6, “The

Asterisk and Dagger (*, f).”

t Correctly attributing ancient manuscripts is not an exact science, and the authorship of the

Tekbne Grammatiké” and its later supplements is a matter of some dispute.2

THE HYPHEN 123

reUOMGCAAN/

r œ N Ó X 'A ? I е го С G1

1t A l TTT Г( ’ ) Ni 6 Ì ХдХ

ттІЫ-Ú ГАРАИ СТА! éc

TAcéy UH AOeeAAYN СЛТО-

óT f ì ха с di eré Аостлфул

тлoп и pei н l arхч? г

АВіЬ яке і Асфо feONÀ

А F Ш М Хтш? ГА Г 1 с го с

оф FAX іЛЛегс-UH Н ІВЫ

! Vf ГѴ О іол ІГТЧО vá.df'brry » * '

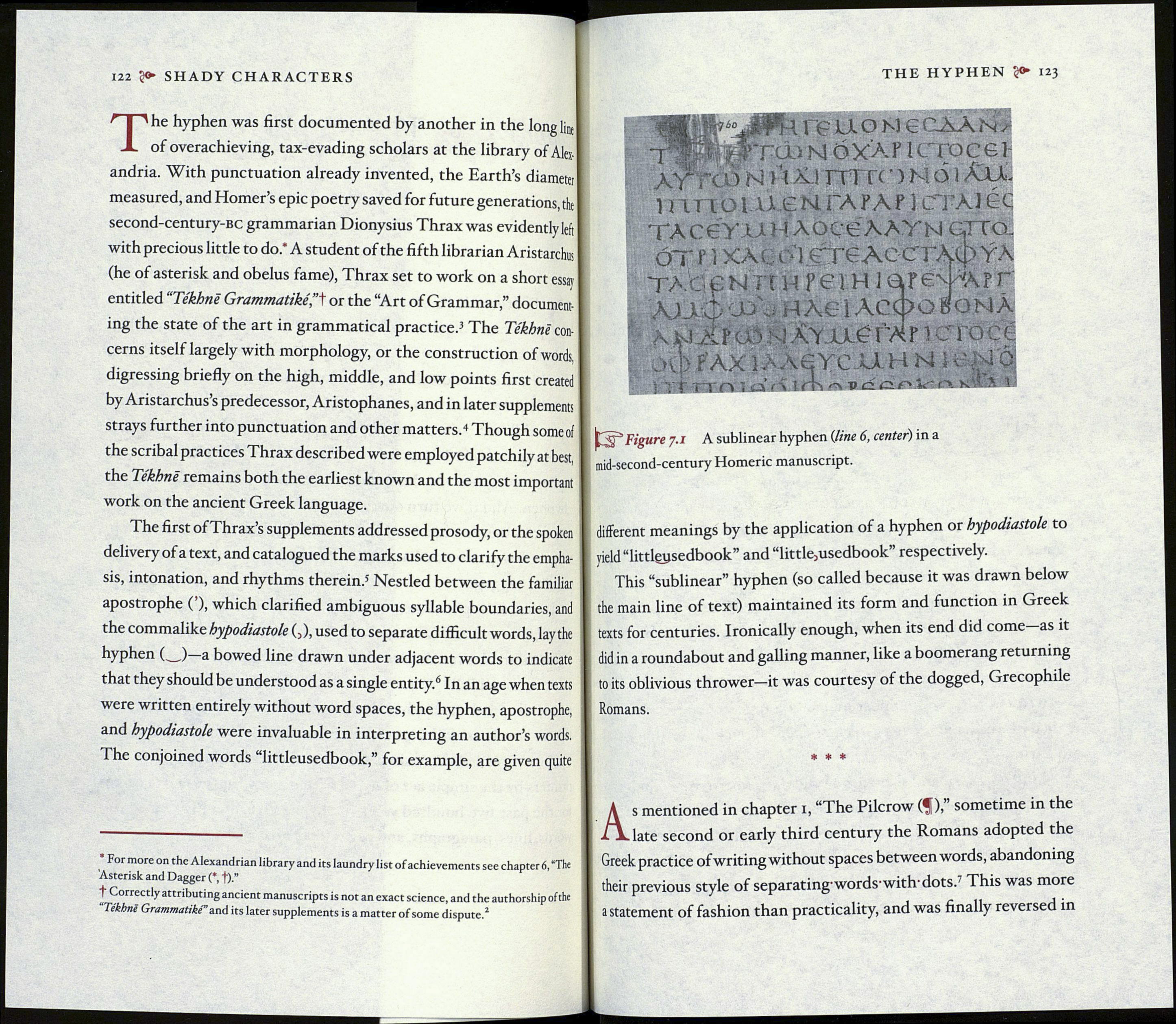

Figure 7.1 A sublinear hyphen {line 6, center) in a

mid-second-century Homeric manuscript.

different meanings by the application of a hyphen or hypodiastole to

yield “littlgysedbook” and “littleusedbook” respectively.

This “sublinear” hyphen (so called because it was drawn below

the main line of text) maintained its form and function in Greek

texts for centuries. Ironically enough, when its end did come as it

did in a roundabout and galling manner, like a boomerang returning

to its oblivious thrower—it was courtesy of the dogged, Grecophile

Romans.

* * *

As mentioned in chapter i, “The Pilcrow (f ),” sometime in the

late second or early third century the Romans adopted the

Greek practice of writing without spaces between words, abandoning

their previous style of separating'words-with'dots.' This was more

a statement of fashion than practicality, and was finally reversed in