no SHADY CHARACTERS

With the proliferation of notes in all forms of document, the prob¬

lem of how to associate a note with the text to which it referred grew

in importance. The solution was simple: embed a letter or symbol in

the text, and label the corresponding note with that same character

Sinai Exodus. 27

mc/i Гспііегн dii« coninvquod tibi certe crû in feandjium. CAP. X X 1111

ЧД Oyfi quoque dixit Afonde ad domimi tu Be Aaron. Nidab * Abiu, &• fcptmgmta м.,ь. и.

IV lfcno „ |it«lA afforibtti, protyl. Solufqnc Но,fa aftrndct ad domini.» ¡Ilfnon

apTTOpmqit,buot:ittcpopuluiarcendcic«mco. Vaut ergo Moyfa A rurrauir plebi

отш. verba domioi.apjut ludjaairrfpondlnj.ciíha,popolo, voa yocp.Ctania ѵуЛа do-

■ninvy.1 ЬоащисП.Гаотопн.

> Ifatl. Mifipptc louent. dt ЛІ11, llracl.lt obmlctun, bolotaoDa.iioodaotnintqii" vT ï2*8

Лта, pacifica. domno.vWot.Tuli, i,a4uc Moyfa dimidi.m pattern bom,ni, A tnlfi,

inctatctaiipattcm .„rem tcfidiiam(ddit fnpc, aitate.Affiimcnfiiuc volumcnLderi. Itcit

^entepopolo.^da^nit.Omniaouailtan.to.cfidominu.faciemm.lcerimmobedii-

,crh'r“ “ P°H". * >'t. Hie ell borni, ГшЫ,. ouod

pepigli domimi, vobifcu fiipcr conclu ¡cntiotiibui híi. Afcendctúntqc Moyfei A Aaron

^ Т^^"'"ІГТ°,!Ы'Ы:*'ѵ‘'1''шпЫс",Г"СІЛ<“ЬН'Ьо,сіо,'

«ofrrhi.K.,,1 quaü OPUS lapida úpphmm.íftjuaC dum cum fetenú cfhNcc fu per cor qui procul recef-

аязй.* Ictani ile {¡Un Iliaci, mifit manu fila: ѵііісттфге deum, Ar comedcrôt.ac üibcrinn ^Di- „ _

fSü&S&t bloyfai,Afcendc«I„¡„monrem,Ariloibiidabdonetibj ,ab“>, Sf-S

Srîlïi feipfi.vr docea, eoi. Sorrtamir MovfaA Iofire oinii- —S’.'“

“*4“, jTTb'írT1“ °£ ln "“".'T'•fcmot'hm "W.EapcöateIdc'donecrcucitamut

т°тт- * 1"b¡““¡‘ E|oru r“r" s™, »gtiî ss!

llluin milic fea dlcbuifftprimo autcmdic vocauit cum de medio caligini, . Erar antcin Vpe

tatfe M'"f 4“ J18"” "T“ fT' montino confitó!,, fil,o„,m lfifí.

"" Ifiacl.vt tolla,,, mih, primula,:

A-abomn, honnnt qmobnvtaicc.acap.cti, ca,.Hiefi,ntan,cmq„n.„¡pe,eí.

S****“ ьГпнГт„' Щ'TT* "^“mthun, A pnnn.ram.ixwdmqne hi, m,«u,dT b,f. Î-Stt

Î??'P I ^ “c,um ™Ь''"«'.рУІІ<«р,е i an thin», Aliena fein, olt.L itS~*

di'™ A™'”'1”"!1’ J'j™m1',a’""’8«”“.*Ауті.та,аben,,Ж.ЬрЗкТГ

А, кп.Аргтта, «donundutpliod.ac rationale. Facie'nupie nubi Гапйоа™ Ahab.¿-

Sitófef™ff “

•fa*..І В 2~r“&т,(Гст-Et А»иг>Ьь cam auromudiffimointuì te for.,:6d¿fofupra coroni

aurcam per circuirum :* quatuor circulo» aure«, quoi potici per quatuor *rc£i,£¡£*

•«a.. 1 flnt ,n kterc vno.ee duo in altero. Facici quoque ѵсЛсі de licnii fetim Лv

pct стам“10 ^ucefquc’pcr circuì« qui funr in arce laten bui ,vt portetur in eirtiui fem'

per cmnt in arcuili,ncc vnquam cxtTahctur ab cii.Pone'fquc in arca tertifif-.rm.JL J

dabonbi. Fanei 6c propitiarorium de auto.muudiiTimo: du« culutoi A- dim.d ^Uam

Äwi' Г"' “ѴтЧ“ Г“" «*' Chemb ™n, fit Inlatctcvno, A ai«, ¡Í5' °”‘“

S5""- "°: c^ * ГСЬЛПС* C1 fanden,с alaff.A »pc„e„,c o^.iT.“!

•~ZUa,, n“"'T^ "ita Ч«1 ^opetnrnda efi area, in ona pone, L

Î^ ^ n l'l”dcPrar,'.i'l“inatad,efi,ptaptop,t,atotinn, arderne

с ¿a ? chctnhnn, ou, ctunt fupet arcan, геіітгаші, ennöaquc mandabo'pet tcf.lii,

tiidifi * L-aC1C ,ncî1n\ S'1“ ^•'n.bbcntemdu« cubi toi longitudini! A in lati м-Гг

Ä ST?1 ,n cul"'n'"' “ “^Ibn- Ь -au,ab,, eZeZfi

si, ¡S&ìFsaSF^s

que cito lacici de ligmi fetim,& arcundabii auro ad fubuchcndam menùm Para

doii.

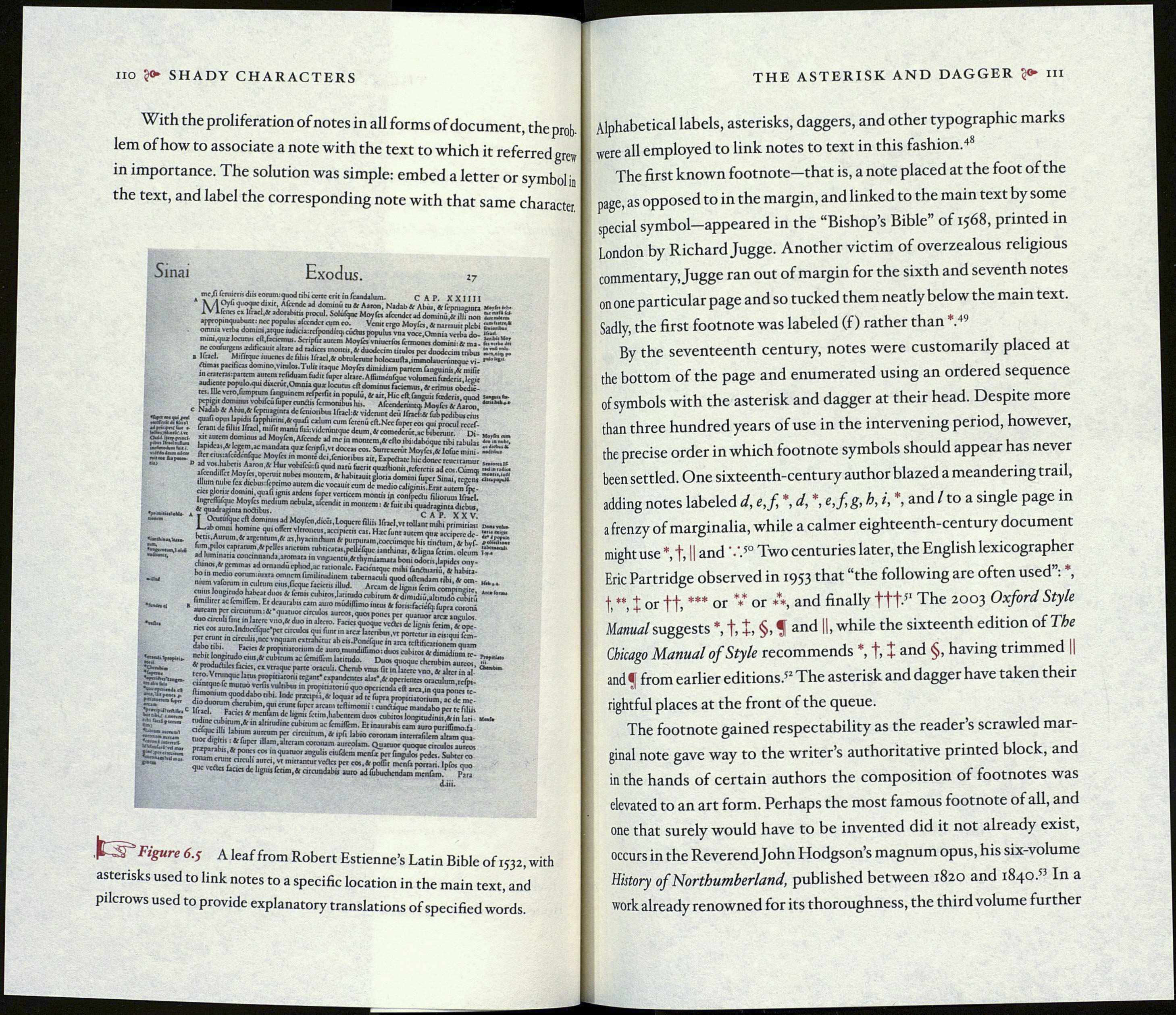

Figure 6.5 A leaf from Robert Estienne’s Latin Bible of 1532, with

asterisks used to link notes to a specific location in the main text, and

pilcrows used to provide explanatory translations of specified words.

THE ASTERISK AND DAGGER ^ in

Alphabetical labels, asterisks, daggers, and other typographic marks

were all employed to link notes to text in this fashion.48

The first known footnote—that is, a note placed at the foot of the

page, as opposed to in the margin, and linked to the main text by some

special symbol-appeared in the “Bishop’s Bible” of 1568, printed in

London by Richard Jugge. Another victim of overzealous religious

commentary, Jugge ran out of margin for the sixth and seventh notes

on one particular page and so tucked them neatly below the main text.

Sadly, the first footnote was labeled (f ) rather than *.49

By the seventeenth century, notes were customarily placed at

the bottom of the page and enumerated using an ordered sequence

of symbols with the asterisk and dagger at their head. Despite more

than three hundred years of use in the intervening period, however,

the precise order in which footnote symbols should appear has never

been settled. One sixteenth-century author blazed a meandering trail,

adding notes labeled d, e,f *, d, *, e,fg, h, i, *, and / to a single page in

a frenzy of marginalia, while a calmer eighteenth-century document

might use t, II and V.s° Two centuries later, the English lexicographer

Eric Partridge observed in 1953 that “the following are often used”: *,

f, **, X or ft. *** or *** or ***> and finady ttt-5' The 2003 Oxford Style

Manual suggests *, t, +, §, 1 and ||, while the sixteenth edition of The

Chicago Manual of Style recommends *, +, % and §, having trimmed ||

and f from earlier editions.52 The asterisk and dagger have taken their

rightful places at the front of the queue.

The footnote gained respectability as the reader’s scrawled mar¬

ginal note gave way to the writer’s authoritative printed block, and

in the hands of certain authors the composition of footnotes was

elevated to an art form. Perhaps the most famous footnote of all, and

one that surely would have to be invented did it not already exist,

occurs in the Reverendjohn Hodgson’s magnum opus, his six-volume

History of Northumberland, published between 1820 and 184o.’3 In a

work already renowned for its thoroughness, the third volume further