102 5»- SHADY CHARACTERS

marked spurious passages in the LXX that did not occur in the origi¬

nal Hebrew; where verses from the Hebrew were found to be missing

from the LXX, he copied them from one of the other Greek transla¬

tions and marked them with an asterisk.23 Also, like Aristarchus, he

occasionally placed the two characters together to indicate that the

ordering of the LXX was at odds with the Hebrew.24 Origen’s sole

addition to this system was the metobelus, or closing obelus: having

marked a line as spurious or missing, he placed a metobelus to mark

the end of the erroneous text.

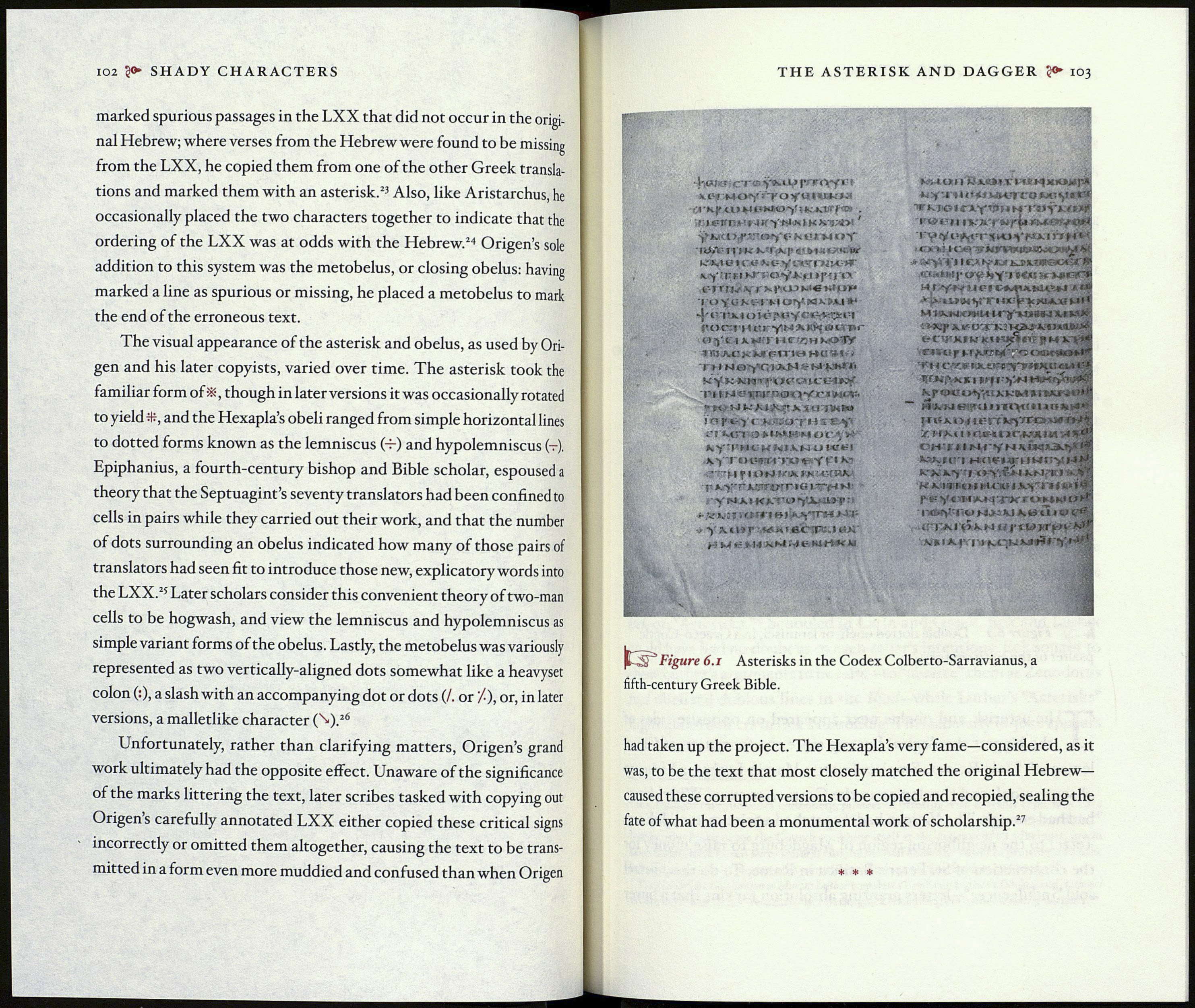

The visual appearance of the asterisk and obelus, as used by Ori¬

gen and his later copyists, varied over time. The asterisk took the

familiar form of *, though in later versions it was occasionally rotated

to yield Ф, and the Hexapla’s obeli ranged from simple horizontal lines

to dotted forms known as the lemniscus (-r) and hypolemniscus (-).

Epiphanius, a fourth-century bishop and Bible scholar, espoused a

theory that the Septuagint’s seventy translators had been confined to

cells in pairs while they carried out their work, and that the number

of dots surrounding an obelus indicated how many of those pairs of

translators had seen fit to introduce those new, explicatory words into

the LXX.25 Later scholars consider this convenient theory of two-man

cells to be hogwash, and view the lemniscus and hypolemniscus as

simple variant forms of the obelus. Lastly, the metobelus was variously

represented as two vertically-aligned dots somewhat like a heavyset

colon (:), a slash with an accompanying dot or dots (/. or /), or, in later

versions, a malletlike character (A).26

Unfortunately, rather than clarifying matters, Origen’s grand

work ultimately had the opposite effect. Unaware of the significance

of the marks littering the text, later scribes tasked with copying out

Origen s carefully annotated LXX either copied these critical signs

incorrectly or omitted them altogether, causing the text to be trans¬

mitted in a form even more muddied and confused than when Origen

THE ASTERISK AND DAGGER 103

.c1'eÿ^ X 1*7 Moyï-I'UYUUKï хуіикпдаух » i » у tre IT rii»- V Г V tscu kl « ШМ М i oyuhti моумхм►* -}' onx i oiv -чау l'oril I cîj-yw ЙНИГ нуi ixѵкг»кпянлхлИУ I H MOi'OXH -H'IJWtfl кук КП' ' Vi I H ST;riri:0( » к ìJk’WY'XSil |»,to «.угнскиан о псе i Tiyriwutnoir»*«' VfUiKYt) уЛЛІ 3 p : i- at л » t nt tri ö » лутги M'r- MOII CliJIVI lIHKlOHf» iiipjuim мктсо ля; у л»'-1 1FK J.<5 «глупИн мт»Улс ту ту <У і>іѴггVP«.i г* М1 < - • : IС < > уѵ * erytl I «.л If х* hjBKimnoi -Ж J» оу цуі ««XI клінггі м гум мрі ілухккч*! I “і < і лр х ог*'КЗ V12XÍ XI пш> я у ». г улг у - ; ci ооіг ЛэН- ЧГлі/ук к I *rf |: >|>J Him л-л lyi oy.ííllH I I • V' гяыучю MJOXI ЛИ lì JS> У? ІГ ГЛ U>IH (7 IW рГрмЮ>' ѴМЛг T»sl'WX»«3l У«-,,‘ : fcs*Figure 6.1 Asterisks in the Codex Colberto-Sarravianus, a had taken up the project. The Hexapla’s very fame—considered, as it

vl'KfximrhloyîXxVfD' .

r I e If г « ’ « -i

УкіСО.ГТоу С- Kt'í. м о Y

тил- гті к к*Г(Х |‘ «< tMi.» reW

кѵм X- »c«?

я m pme не tur >

topi- У с- l.coyu .2 Sf-y

V« KOTO UMI-MI OC, >'

хупкчіити^уі'1 к-

• -ц Р I ОН МЫ I н -erил.

умоу ѵиівсгміоі'

И м *í im xMMfw rt« w

ÍWI'II IVX‘r*»p(«W»y fH

і>шмі^ніфу іоляііі 1

М1ЛЫОШ К'у-лия« J V- X

l-CTKIIJ рм X VI41

Г H СЛ* «ы г »

лр ouoyjuxK’M« rex* » о»

~ нлывуштуниихн«

іічхои err лу/ГЕэнв tHi

У. ИМИniMIJWJl W/O'1

OK’fll M іуіиікіэ.1,1

ЛЯЛІІІ HdPirUMIiyiJI1

к л ітпн иск; i яут«*•<$

ре Г1ХЛН0 HI1'

fifth-century Greek Bible.

was, to be the text that most closely matched the original Hebrew-

caused these corrupted versions to be copied and recopied, sealing the

fate of what had been a monumental work of scholarship.27