84 S<* SHADY CHARACTERS

POSITION NU Typewheel Character Set

UN8HIFT ABCDEFGH IJ KLM N 0 PQRSTUVWXYZ 1 2 3 4 5 в 7 8 9 0 / . - , ; ;

SHUT !"••%*■ ( ) ?>-<..

0©©©®(D©®G)©©(D©

©@©©©@00©®®©©

Ѳ©®@®©оо®©ѳ©ѳѳ

@Q©Q®Q©®©0©0

С )

V у

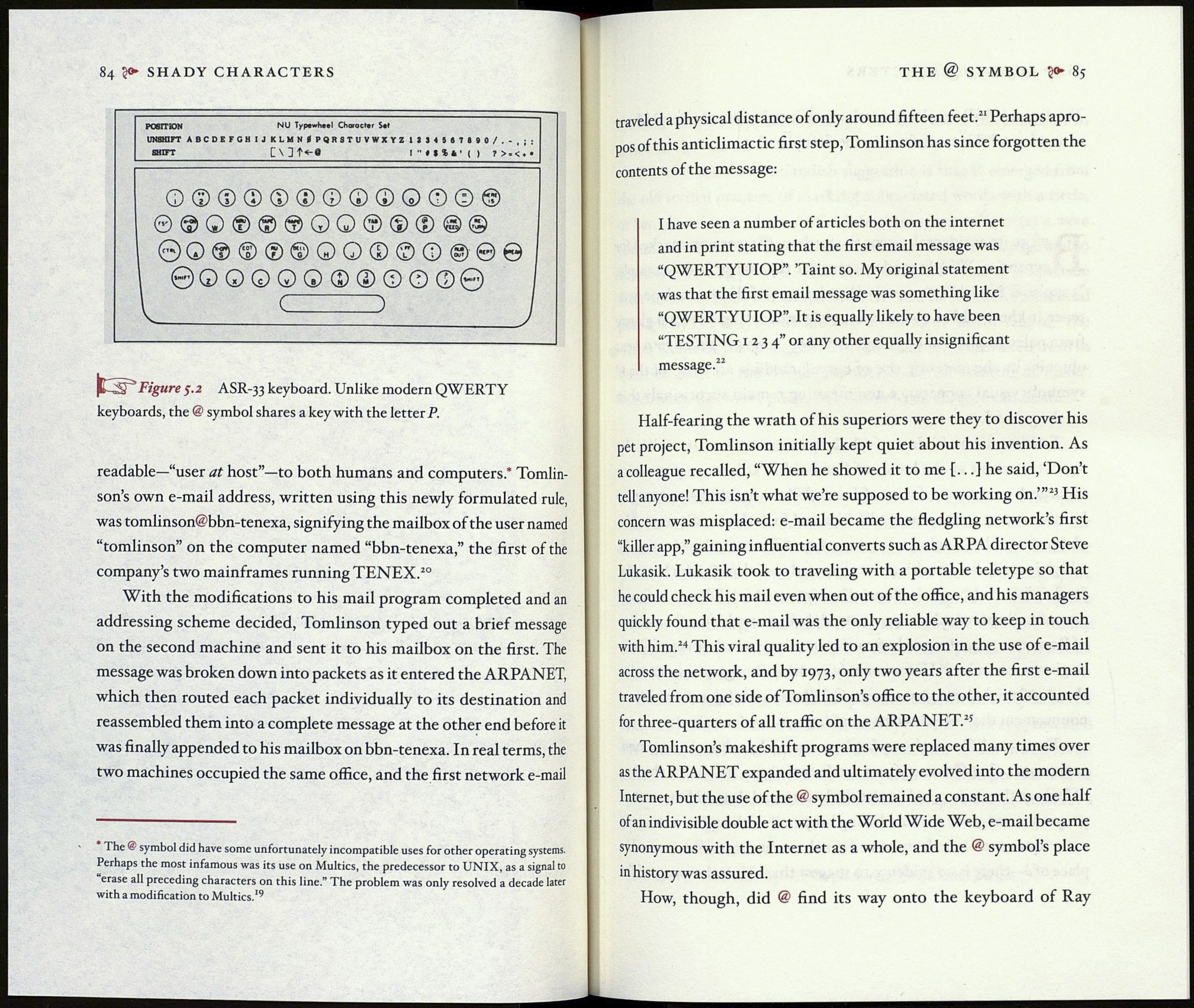

(t-áJ 5Figure <¡.2 ASR-33 keyboard. Unlike modern QWERTY

keyboards, the @ symbol shares a key with the letter P.

readable—“user at host”—to both humans and computers.* Tomlin¬

son’s own e-mail address, written using this newly formulated rule,

was tomlinson@bbn-tenexa, signifying the mailbox of the user named

“tomlinson” on the computer named “bbn-tenexa,” the first of the

company’s two mainframes running TENEX.20

With the modifications to his mail program completed and an

addressing scheme decided, Tomlinson typed out a brief message

on the second machine and sent it to his mailbox on the first. The

message was broken down into packets as it entered the ARPANET,

which then routed each packet individually to its destination and

reassembled them into a complete message at the other end before it

was finally appended to his mailbox on bbn-tenexa. In real terms, the

two machines occupied the same office, and the first network e-mail

The @ symbol did have some unfortunately incompatible uses for other operating systems.

Perhaps the most infamous was its use on Multics, the predecessor to UNIX, as a signal to

erase all preceding characters on this line.” The problem was only resolved a decade later

with a modification to Multics.'9

THE @ SYMBOL 8j

traveled a physical distance of only around fifteen feet.2’ Perhaps apro¬

pos of this anticlimactic first step, Tomlinson has since forgotten the

contents of the message:

I have seen a number of articles both on the internet

and in print stating that the first email message was

“QWERTYUIOP”. ’Taint so. My original statement

was that the first email message was something like

“QWERTYUIOP”. It is equally likely to have been

“TESTING 1234” or any other equally insignificant

message.22

Half-fearing the wrath of his superiors were they to discover his

pet project, Tomlinson initially kept quiet about his invention. As

a colleague recalled, “When he showed it to me [...] he said, ‘Don’t

tell anyone! This isn’t what we’re supposed to be working on.’”23 His

concern was misplaced: e-mail became the fledgling network’s first

“killer app,” gaining influential converts such as ARPA director Steve

Lukasik. Lukasik took to traveling with a portable teletype so that

he could check his mail even when out of the office, and his managers

quickly found that e-mail was the only reliable way to keep in touch

with him.24 This viral quality led to an explosion in the use of e-mail

across the network, and by 1973, only two years after the first e-mail

traveled from one side of Tomlinson’s office to the other, it accounted

for three-quarters of all traffic on the ARPANET.25

Tomlinson’s makeshift programs were replaced many times over

as the ARPANET expanded and ultimately evolved into the modern

Internet, but the use of the @ symbol remained a constant. As one half

of an indivisible double act with the World Wide Web, e-mail became

synonymous with the Internet as a whole, and the @ symbol’s place

in history was assured.

How, though, did @ find its way onto the keyboard of Ray