82 SHADY CHARACTERS

Atlantic via satellite link) but it would also be the first to use a novel

and untested technique called “packet switching” on a grand scale.”

Packet switching relied not on a direct connection between sender

and recipient, but instead sent messages from source to destination

by a series of hops across the network, fluidly routing them around

broken or congested links.'3

Some of the technology heavyweights of the time did not even

bid. IBM, firmly wedded to the traditional (and profitable) main¬

frame computer, could not see an economically viable way to build

the network, while Bell Labs’ parent company, AT&T, flatly refused

to believe that packet switching would ever work.'4 In the end, an

intricately detailed two-hundred-page proposal submitted by rela¬

tive underdogs BBN secured the contract, and construction of the

ARPANET began in 1969. The project was a success, and by 1971

nineteen separate computers were communicating across links that

spanned the continental United States.'5

Working in BBN’s headquarters, Ray Tomlinson had not been

directly involved in building the network but was instead employed

in writing programs to make use of it.'6 At the time, electronic mail

already existed in a primitive form, working on the same principle

as an office’s array of pigeonholes: one command left a message for a

named user in a “mailbox” file, and another let the recipient retrieve

it. These messages were transmitted temporally but not spatially, and

never left their host computer. Sender and recipient were effectively

tied to the same machine.'7

Taking a detour from his current assignment, Tomlinson saw an

opportunity to combine this local mailbox system with some of his

previous work. He used CPYNET, a command that sent files from

one computer to another, as the basis for an improved e-mail program

that could modify a mailbox file on any computer on the network, but

the problem remained as to how such a message should be addressed.'8

THE @ SYMBOL 83

LINE

GUIDE

WINDOW

TAPE

PUNCH

ROTARY

DIALER

TAPE .

READER

NAMEPLATE

CHAD

■STAND

CONTAINER

(LEFT FRONT VIEW)

COPY HOLDER

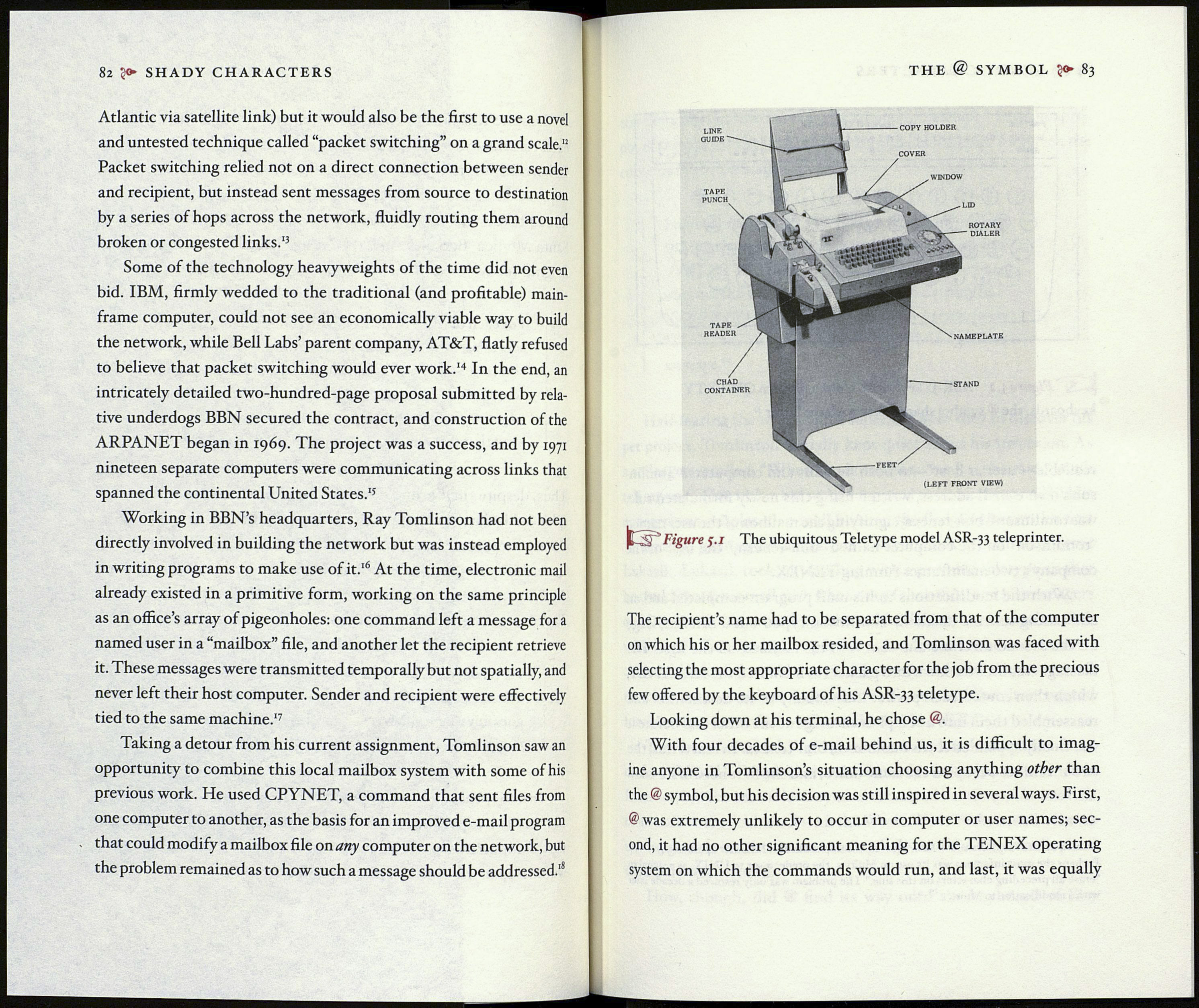

^1:5 ’’Figure $.i The ubiquitous Teletype model ASR-33 teleprinter.

The recipient’s name had to be separated from that of the computer

on which his or her mailbox resided, and Tomlinson was faced with

selecting the most appropriate character for the job from the precious

few offered by the keyboard of his ASR-33 teletype.

Looking down at his terminal, he chose @.

With four decades of e-mail behind us, it is difficult to imag¬

ine anyone in Tomlinson’s situation choosing anything other than

the @ symbol, but his decision was still inspired in several ways. First,

@ was extremely unlikely to occur in computer or user names; sec¬

ond, it had no other significant meaning for the TENEX operating

system on which the commands would run, and last, it was equally