72 ?<► SHADY CHARACTERS

many of its letters required several individual pen strokes to draw,

and deciphering the closely packed letterforms, with their extreme

contrasts between light and heavy strokes, was an exercise in perse¬

verance. For many readers, blackletter was inextricably linked with

the Church: not only was its architectural regularity redolent of the

vaulted cathedrals at Rheims and Notre-Dame, but the painstaking

effort required to create and consume blackletter works may actually

have been welcomed by its most ardent practitioners.47 As one modern

commentator suggested:

When writing, monks were not in a hurry. They wrote in

honor of God. This is the only explanation of the forms

of textura [a type of blackletter], so difficult to read but so

decorative.4®

Thus, when Johannes Gutenberg first printed his forty-two-line Bible

in the mid-i45os, blackletter was the obvious alphabet in which to set

it.49 And though the first competing roman type was cut only a few

years later by printers from Gutenberg’s own hometown, blackletter

type continued to dominate German books for centuries.

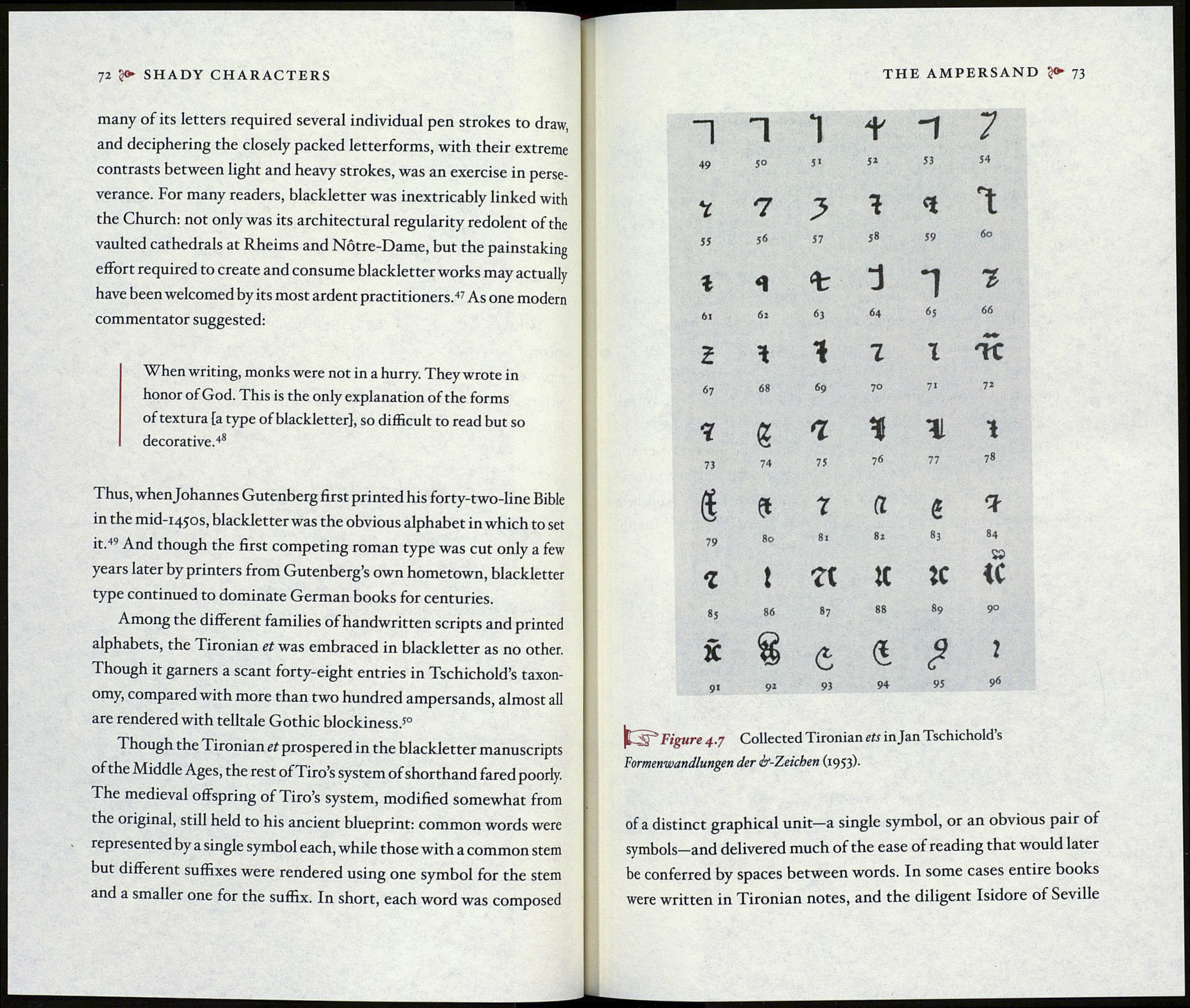

Among the different families of handwritten scripts and printed

alphabets, the Tironian et was embraced in blackletter as no other.

Though it garners a scant forty-eight entries in Tschichold’s taxon-

omy, compared with more than two hundred ampersands, almost all

are rendered with telltale Gothic blockiness.s°

Though the Tironian et prospered in the blackletter manuscripts

of the Middle Ages, the rest of Tiro’s system of shorthand fared poorly.

The medieval offspring of Tiro’s system, modified somewhat from

the original, still held to his ancient blueprint: common words were

represented by a single symbol each, while those with a common stem

but different suffixes were rendered using one symbol for the stem

and a smaller one for the suffix. In short, each word was composed

THE AMPERSAND 73

1

1

1

t

-1

7

49

5°

h

5*

53

54

7

7

У

4

*

1

55

56

57

58

59

бо

г

<1

%

d

1

г

6i

6i

63

64

65

66

2

*

i

7

I

67

68

69

70

71

72

4

£

7

ч

г

1

73

74

75

76

77

78

i

et

r

a

ê

?

79

80

81

82

83

84

г

t

X

к

»

ІС

»5

86

87

88

89

9°

X

8

6

4

?

2

91

92

93

94

95

96

Figure 4.7 Collected Tironian ets injan Tschichold’s

Formenwandlungen der ¿/-Zeichen (1953).

of a distinct graphical unit—a single symbol, or an obvious pair of

symbols—and delivered much of the ease of reading that would later

be conferred by spaces between words. In some cases entire books

were written in Tironian notes, and the diligent Isidore of Seville