52 SHADY CHARACTERS

orphaned at the center of a fourth row.51 This layout was controversial.

Accountants, whose calculator keypads were numbered from 9 down

to o, complained that the proposed out-of-order placement of the zero

was an affront to mathematical consistency. The (winning) counter¬

argument pointed out that on rotary dial phones, each number

doubled as a set of letters for mnemonic purposes—2 = abc, 3 = def,

4 = GHi, and so forth—and that reversing the buttons’ proposed posi¬

tions would ruin their corresponding alphabetical order.52

The next problem faced was linguistic rather than mathematical,

when, in 1968, the two unused buttons either side of the zero were

finally made available for public use in controlling menus and other

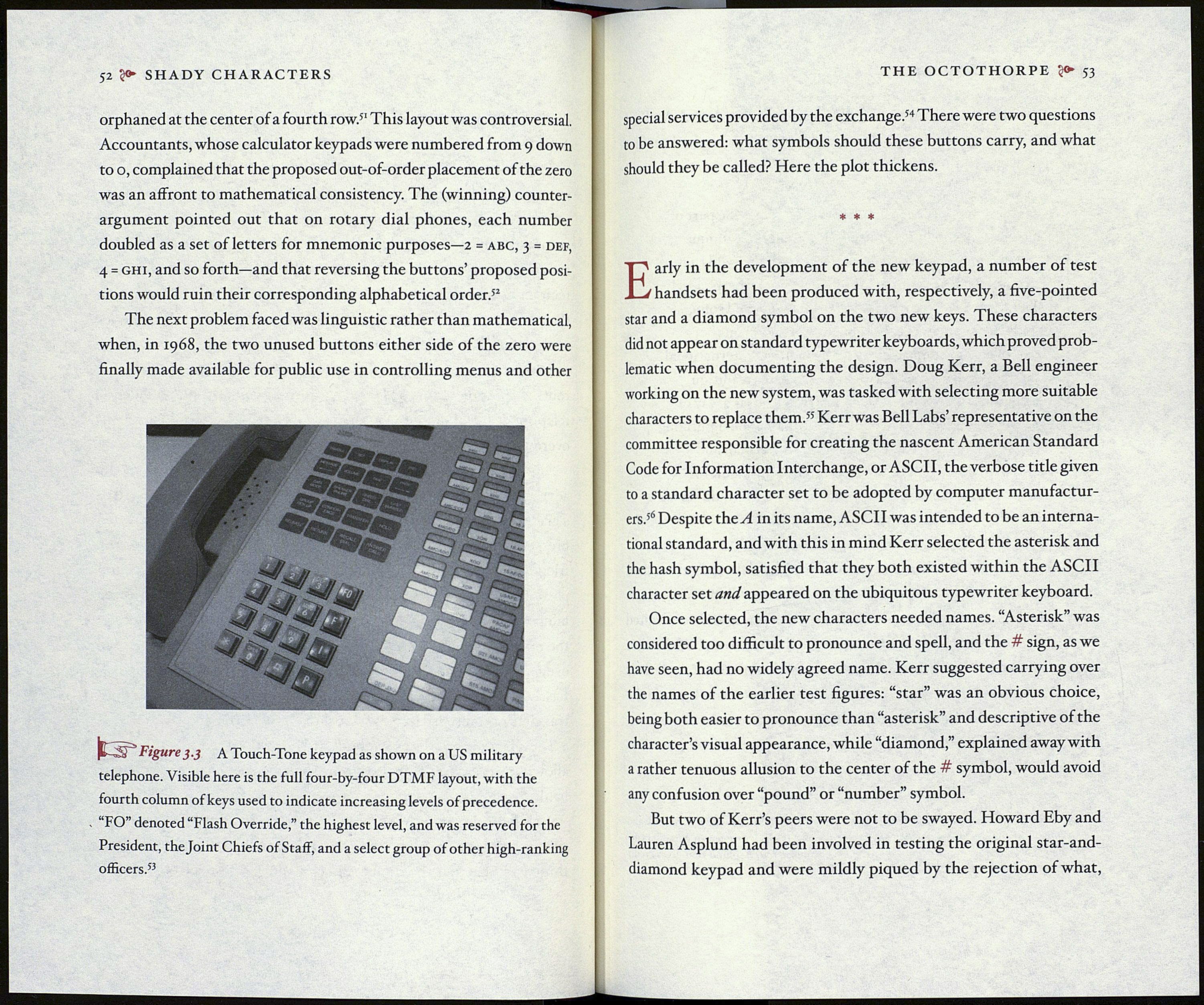

fUST” Figure 3.3 A Touch-Tone keypad as shown on a US military

telephone. Visible here is the full four-by-four DTMF layout, with the

fourth column of keys used to indicate increasing levels of precedence.

“FO” denoted “Flash Override,” the highest level, and was reserved for the

President, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and a select group of other high-ranking

officers.53

THE OCTOTHORPE ?<► 53

special services provided by the exchange.54 There were two questions

to be answered: what symbols should these buttons carry, and what

should they be called? Here the plot thickens.

* * *

Early in the development of the new keypad, a number of test

handsets had been produced with, respectively, a five-pointed

star and a diamond symbol on the two new keys. These characters

did not appear on standard typewriter keyboards, which proved prob¬

lematic when documenting the design. Doug Kerr, a Bell engineer

working on the new system, was tasked with selecting more suitable

characters to replace them.55 Kerr was Bell Labs’ representative on the

committee responsible for creating the nascent American Standard

Code for Information Interchange, or ASCII, the verbose title given

to a standard character set to be adopted by computer manufactur¬

ers.56 Despite the A in its name, ASCII was intended to be an interna¬

tional standard, and with this in mind Kerr selected the asterisk and

the hash symbol, satisfied that they both existed within the ASCII

character set and appeared on the ubiquitous typewriter keyboard.

Once selected, the new characters needed names. “Asterisk” was

considered too difficult to pronounce and spell, and the # sign, as we

have seen, had no widely agreed name. Kerr suggested carrying over

the names of the earlier test figures: “star” was an obvious choice,

being both easier to pronounce than “asterisk” and descriptive of the

character’s visual appearance, while “diamond,” explained away with

a rather tenuous allusion to the center of the # symbol, would avoid

any confusion over “pound” or “number” symbol.

But two of Kerr’s peers were not to be swayed. Howard Eby and

Lauren Asplund had been involved in testing the original star-and-

diamond keypad and were mildly piqued by the rejection of what,