20 SHADY CHARACTERS

liberal enough by 1949 that the sculpture could be sold at auction.'6

Even then, Gill’s original title for the piece (as recorded in his private

diary) was still considered too brazen. For public consumption, the

cheerfully direct They (big) group fucking became the rather more cir¬

cumspect Ecstasy.57

Despite frequent forays into then-taboo subjects, after his death

Gill remained well known mainly for his artistic successes and staunch

Catholicism. The Eric Gill known to his close-knit family and follow¬

ers, however, was a startlingly different man. In 1961, twenty-one years

after his death, the BBC broadcast an hour-long radio documentary

about the artist, and in it could be discerned the first hints of the

extraordinary gulf between Gill’s public façade and the reality of his

private life. Interviewed for the program, Gill’s partner René Hague—

now married to Gill’s daughter Joan—spoke about his father-in-law’s

attitude toward evil:

I wonder whether Eric really believed in evil. He would

talk about the evils of industrialism, he would talk about

things going wrong, but he certainly didn’t believe that

there was any “bad thing.” He didn’t believe in evil in that

sense, that anything in nature could be evil. That was

one of the reasons why he was willing to try anything,

anything at all, but quite literally. Either right or wrong,

or supposed to be right or wrong, he’d say “Let’s try it, let’s

try it once, anyway.”58

The awful truth behind Hague’s musings became clear in 1989 when

an unflinching biography revealed adultery, incest, child abuse, and

even bestiality within the Gill household.59 The artist’s posthumous

reputation was rocked by these revelations, yet despite this (or perhaps

partly because of it), Gill remains a resonant name within the typo¬

graphical world and Essay one of his most enduring contributions to it.

THE PILCROW $<► 21

* * *

Despite occasional celebrity appearances as a paragraph mark

(such as in An Essay on Typography), the pilcrow remains largely

alienated from its traditional role. As compensation, perhaps, it has

since acquired a sort of talismanic power for those in the know, espe¬

cially in the worlds of typography, design, and literature. Jonathan

Hoefler of the type design firm Hoefler & Frere-Jones (the company

5 5 f f

11 11Í

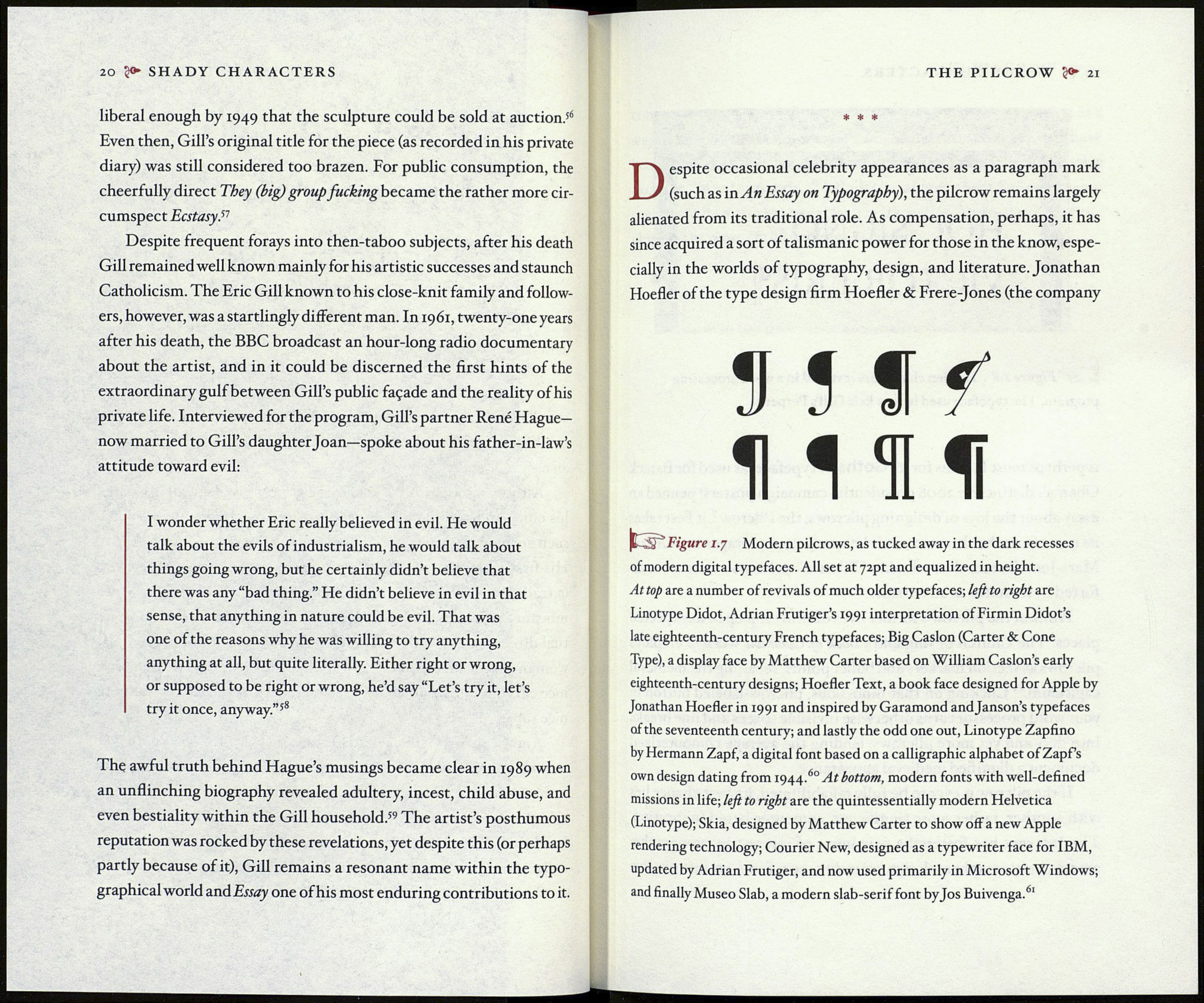

^ : Figure 1.7 Modern pilcrows, as tucked away in the dark recesses

of modern digital typefaces. All set at 72pt and equalized in height.

At top are a number of revivals of much older typefaces; left to right are

Linotype Didot, Adrian Frutiger’s 1991 interpretation of Firmin Didot’s

late eighteenth-century French typefaces; Big Caslon (Carter & Cone

Type), a display face by Matthew Carter based on William Caslon’s early

eighteenth-century designs; Hoefler Text, a book face designed for Apple by

Jonathan Hoefler in 1991 and inspired by Garamond andjanson’s typefaces

of the seventeenth century; and lastly the odd one out, Linotype Zapfino

by Hermann Zapf, a digital font based on a calligraphic alphabet of Zapf’s

own design dating from 1944.60 At bottom, modern fonts with well-defined

missions in life; left to right are the quintessential^ modern Helvetica

(Linotype); Skia, designed by Matthew Carter to show off a new Apple

rendering technology; Courier New, designed as a typewriter face for IBM,

updated by Adrian Frutiger, and now used primarily in Microsoft Windows;

and finally Museo Slab, a modern slab-serif font byjos Buivenga.61