14 3» SHADY CHARACTERS

of ways: monks went ad capitulum, “to the chapter (meeting),” to hear

a chapter from the book of their religious orders, or “chapter-book,”

read out in the “chapter room.”37

Monastic scriptoria worked on the same principle as factory

production lines, with each stage of book production delegated to

a specialist. Depending on the relative wealth of a given monastery,

this process sometimes began even before a scribe put pen to paper,

with the preparation of animal-hide parchment using the skins of

livestock reared on the monastery’s land.38 With parchment in hand,

whether produced by the monastery itself or bought from a profes¬

sional parchmenter,” a scribe would then painstakingly copy out the

body of the text, often by lamplight (candles were forbidden because

of the risk of fire).39 He would take care to leave spaces so that a “rubri-

cator” could later embellish the work with elaborate initial letters (or

“versais”), headings, and other section marks. Named for the Latin

rubrico, “to color red,” rubricators often worked in contrasting red ink,

which not only added a decorative flourish but also guided the eye to

important divisions in the text.40 In the hands of the rubricators, С

for capitulum was soon accessorized by a vertical bar, as were other

litterae notabiliores in the fashion of the time; later, the resultant bowl

was filled in and so с for capitulum became the familiar reversed-P of

the pilcrow.41

As the symbol’s appearance changed, so too did its usage. At first

it only marked chapters, but soon after it started to pepper texts as

a paragraph or even sentence marker, breaking a block of running

text into meaningful sections as the writer saw fit. f This style of

usage yielded very compact text, harking back, perhaps, to the not-so-

distant practice o fscriptio continuad2 Ultimately, though, the utility of

the paragraph overrode the need for efficiency and became so impor¬

tant as to warrant a new line—prefixed with a pilcrow, of course.43

Щ The pilcrow’s name—pithy, familiar, and archaic at the same

time—moved with the character during its transformation from С for

THE PILCROW 15

■

Я

iè aó» qufoMufmc 4|fÌ94jm’*nf

(ffittìVf Jpu »mytoar dmm;cf«unyr

I rotuCtmiiLfù? <"?

Jpcnwy aSrôcT «j tïwâUf» яист^сой

tyic favo

6ìiò pi comment- coiÆ-^ц-? .TemÇêuctef

(м2 гг «Гtyicl. Stereo«1 aréò '

yffp oc гіго1ді1іЦлл-^(л°9 [hic fol»

lauf ihr Sïrê ycyû-A SVrtu m^oSîa

iimrrî tya lurutr m(otSatT

cfg-й (ЯйГі fui?-ив «iS’-cwf ftrt

ЙТО aqwtc Sk ^clouta

—^-uKuiluW SliLr^puqoiibi Octv

“ iiiLaïuâjàfea

М-іШШ

—,

(ifliouif y»r«u>fJir «fqiiifAt Sncetafg1 s

«Tr^u© Su iAtptcv с »**£ SbcciTMp p

«lÔinfÂif Pietri m лфГо^оиС ifllfcyc I

чбг mej ncr ttic*inil«aC tier ciifuÇ fWrwir?

titrât" ли<-7 ¿yíque rt>mpC«U“

;| Ípíro fmentS^ mrfou 5>“Л>і Лиг tûw-

tîî âltr fiotti 3?tr A6U9* et? {e

to иг fuiuÜ atòif 110m» op ntßtm(rnt <&

(Ьпѵуіг-чТ ÖVJ&ttr £1 fe ocrutrftu uç

^ «j cOtA ctmjbar »‘i &fbytr fa (

йсшис* пЗрсПсіЛ-Ѵг- wí1 fcor tu jjjbttu

гЩШ

Я|

mk

тш

'Ж

ШввШ I

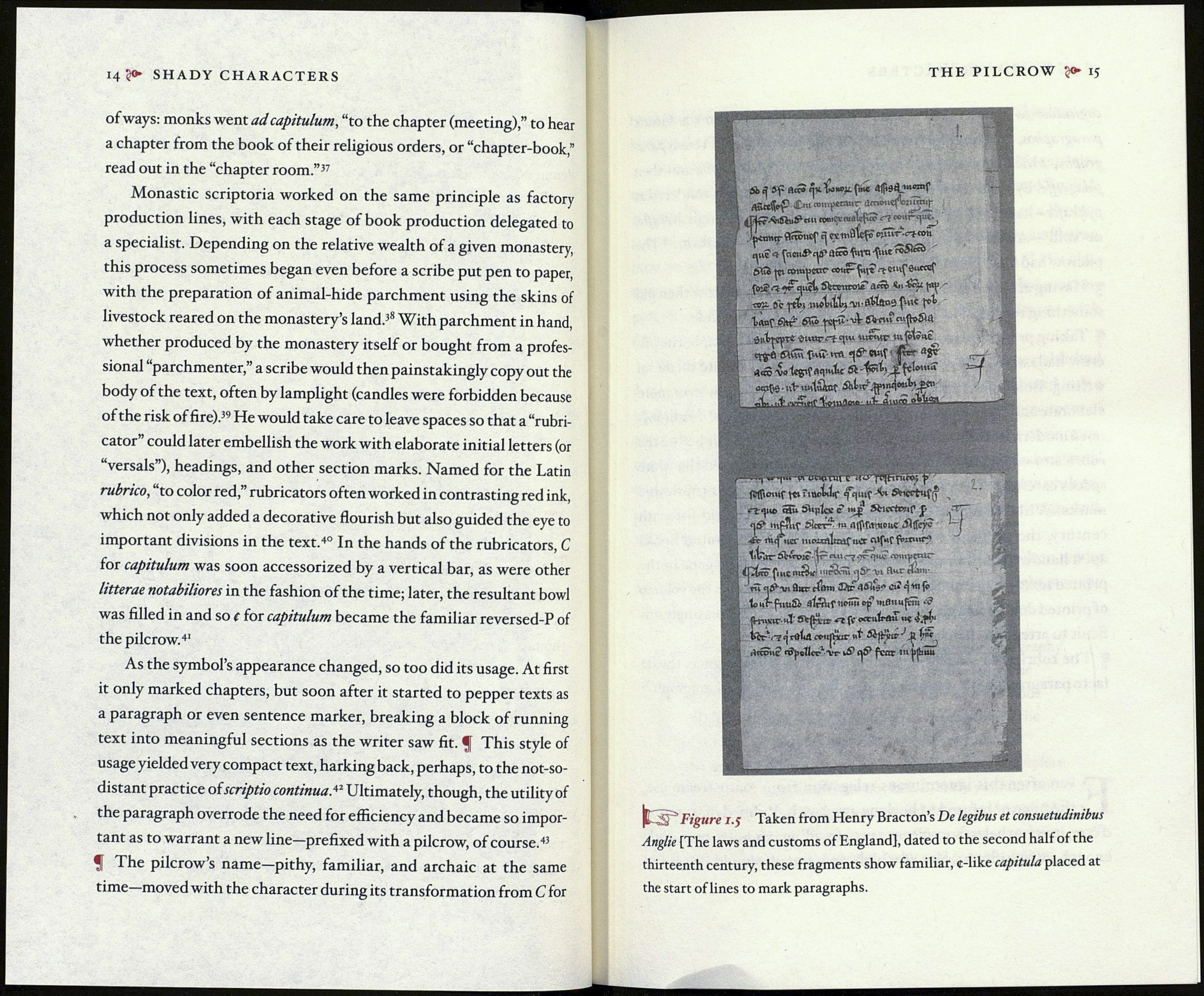

Figure 1.5 Taken from Henry Bracton’s De legibus et consuetudinibus

Anglie [The laws and customs of England], dated to the second half of the

thirteenth century, these fragments show familiar, e-like capitula placed at

the start of lines to mark paragraphs.