12^ SHADY CHARACTERS

•'гойтХс*. •

ctnt 0*1^ *4ifS6örfffi'Cccli»i Cjuoj

pt-ссдхс Ceoixxx-df' GUert&rrc. ei •

^ eJ ihm ob i \л‘Г Í ndvcimortì- pei-тл«

frc ■1v^nrtJ4*cricercfe оттІшгЛіеІніГ

ette.ѵё/йле- ; "рлт іТсшГесстоІо!»

inftilrectcctic rejeT< téíctffcpocre«

^чЗ^іоріс-таиГ mtncM>ccrrr

tti-èâfeffitMur «licer» reft * -\.lttejV

, '-hfabfvucc procjuefceLyTTiOfínccC

fWjulrarccT praefcccT-"^

•'I"objeer aero Increfccbceceof'cjtccnf; yf[¡

SoHpecíluiorm - ѵЧ/т

отиilitif ncc-nornLüf litçjutbuf'

сЬгрегЧТіЧтор ; (Armine cine

TI1CCJ71CC TUcîtClCCTua CJUIÆ 110*7'

ejjmuf fW*bidu»n ргдесі*ргсггц.\

t4¿ nonccmbulcrutmaf fincenwi^

cor*cc*ivte-óunc.clrje'ffccuri

datAewlunraytem сади» Cos-me-

J * f ; ' 1/

cam • T'ectp»

fjmi mtHim;» C^^jredrc ennrtmiíit

mol-i itia^rcjuccmuuiet'*-;

£ ¿dem iraxjue-cJie- comigr итТ<г;*гл

plttrTXcjuet inctuitœrvsmedopy'-

иѵШі^Гл- Axxâir&L hipropcr-iufn

лЬтісс Rollìi’ ptrif fat-\

CJ ùb -ct^vJictc риеічхт fepremuimr-

cydemontum nomine- Afmodcur

, ,Vpjxcidet^xceoC »wx«cmçt|^

tffeiTC .ídeccm . t*T*£p c«*n^*f»ocul

peeirîia: mcfepocrcV pueUtvm'fV

ttxc. iocjai cjuopittfîronum

' (ttmuf k'untcm'iÜccwi Qvpecctr

тар cjucctndr dccttipnf* efè- W

cjuipdern fiiccm «amcjuccm mu

r&hr ccl»eo *

eictp «f>ccr cwt

Зуппсстих» tçvor*-

îxmnuin opufeo jy

-ne!»/1 'A7cielcctdr^e mccnuum fîxA.

Г-um uicrum au<-‘_corif»îciui po

хаіГГЛ' de^twcctfj -\j| naepoce

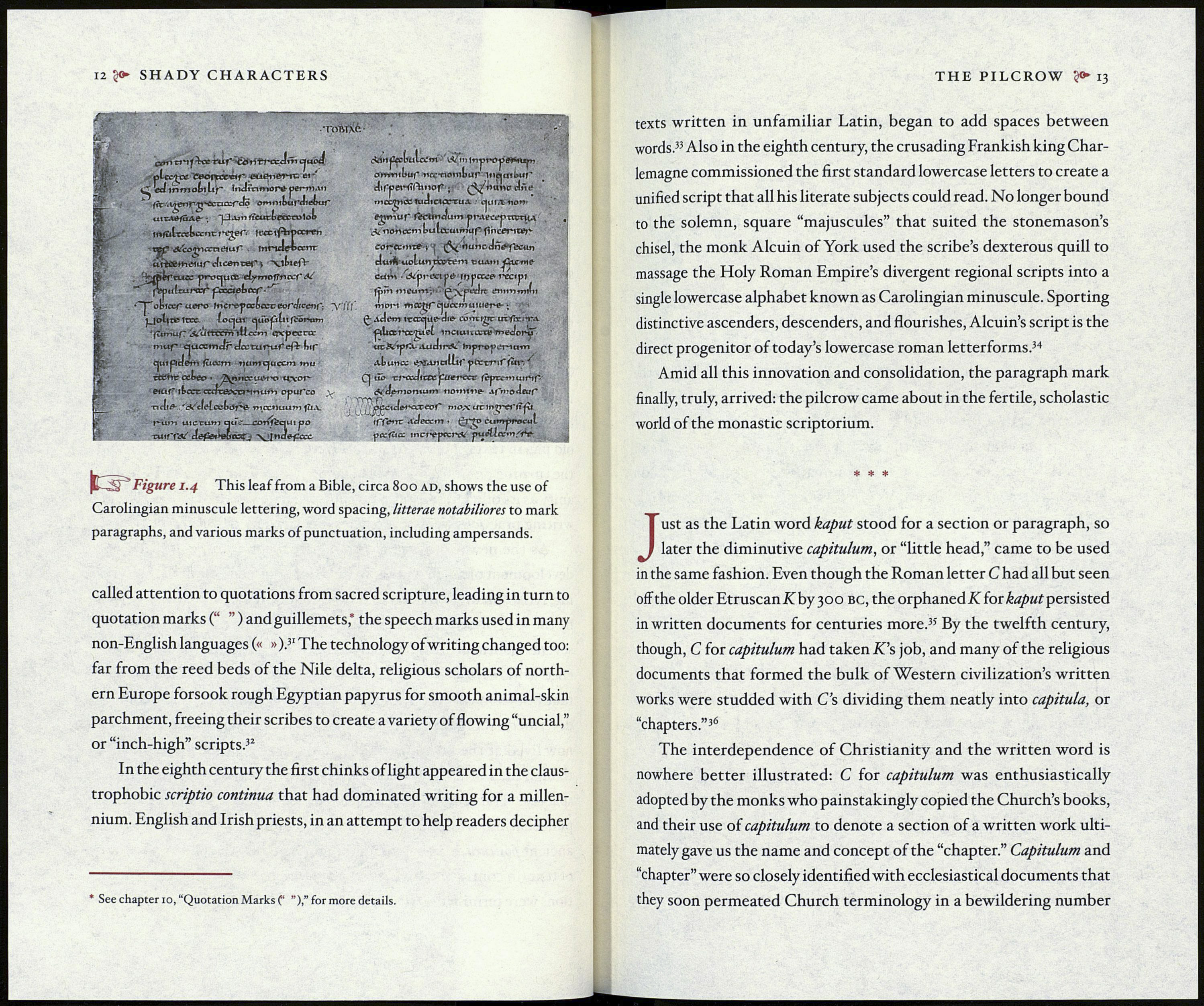

(Csf5 Figure 1.4 This leaf from a Bible, circa 800 ad, shows the use of

Carolingian minuscule lettering, word spacing, litterae notabiliores to mark

paragraphs, and various marks of punctuation, including ampersands.

called attention to quotations from sacred scripture, leading in turn to

quotation marks (“ ” ) and guillemets* the speech marks used in many

non-English languages (« » ).3’ The technology of writing changed too:

far from the reed beds of the Nile delta, religious scholars of north¬

ern Europe forsook rough Egyptian papyrus for smooth animal-skin

parchment, freeing their scribes to create a variety of flowing “uncial,”

or “inch-high” scripts.32

In the eighth century the first chinks of light appeared in the claus¬

trophobic scriptio continua that had dominated writing for a millen¬

nium. English and Irish priests, in an attempt to help readers decipher

* See chapter 10, “Quotation Marks f ”),” for more details.

THE PILCROW ?»■ 13

texts written in unfamiliar Latin, began to add spaces between

words.33 Also in the eighth century, the crusading Frankish king Char¬

lemagne commissioned the first standard lowercase letters to create a

unified script that all his literate subjects could read. No longer bound

to the solemn, square “majuscules” that suited the stonemason’s

chisel, the monk Alcuin of York used the scribe’s dexterous quill to

massage the Holy Roman Empire’s divergent regional scripts into a

single lowercase alphabet known as Carolingian minuscule. Sporting

distinctive ascenders, descenders, and flourishes, Alcuin’s script is the

direct progenitor of today’s lowercase roman letterforms.34

Amid all this innovation and consolidation, the paragraph mark

finally, truly, arrived: the pilcrow came about in the fertile, scholastic

world of the monastic scriptorium.

* * *

Just as the Latin word kaput stood for a section or paragraph, so

later the diminutive capitulum, or “little head,” came to be used

in the same fashion. Even though the Roman letter С had all but seen

off the older Etruscan Aby 300 вс, the orphaned A foretti persisted

in written documents for centuries more.35 By the twelfth century,

though, С for capitulum had taken K’s job, and many of the religious

documents that formed the bulk of Western civilization’s written

works were studded with C’s dividing them neatly into capitula, or

“chapters.”36

The interdependence of Christianity and the written word is

nowhere better illustrated: С for capitulum was enthusiastically

adopted by the monks who painstakingly copied the Church’s books,

and their use of capitulum to denote a section of a written work ulti¬

mately gave us the name and concept of the “chapter.” Capitulum and

“chapter” were so closely identified with ecclesiastical documents that

they soon permeated Church terminology in a bewildering number