8 ?<► SHADY CHARACTERS

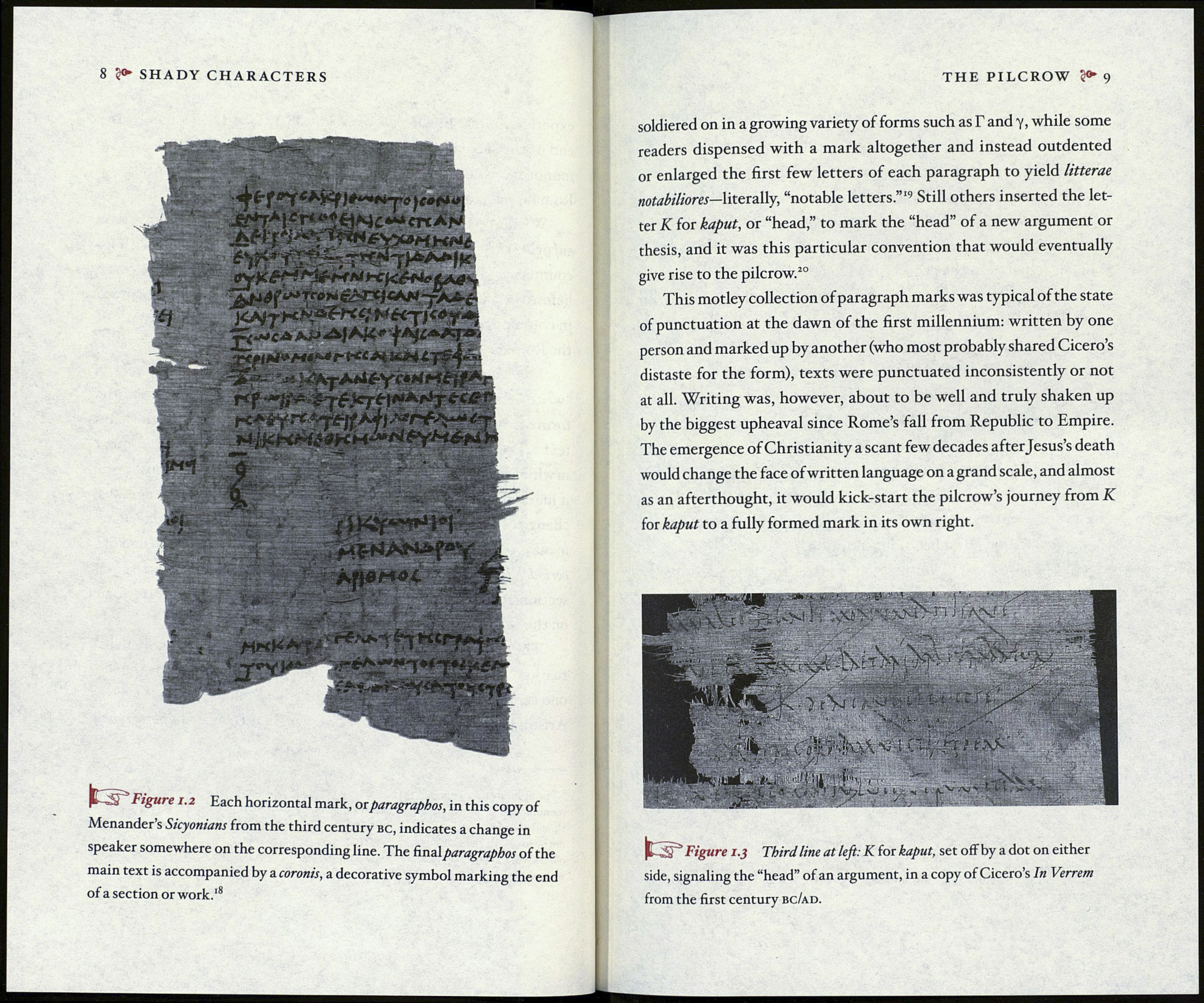

ft^ST Figure 1.2 Each horizontal mark, от paragraphes, in this copy of

Menander’s Sicyonians from the third century вс, indicates a change in

speaker somewhere on the corresponding line. The finalparagraphos of the

main text is accompanied by a coronis, a decorative symbol marking the end

of a section or work.’8

THE PILCROW ?<► 9

soldiered on in a growing variety of forms such as Г and у, while some

readers dispensed with a mark altogether and instead outdented

or enlarged the first few letters of each paragraph to yield litterae

notabiliores—literally, “notable letters.”'9 Still others inserted the let¬

ter К for kaput, or “head,” to mark the “head” of a new argument or

thesis, and it was this particular convention that would eventually

give rise to the pilcrow.20

This motley collection of paragraph marks was typical of the state

of punctuation at the dawn of the first millennium: written by one

person and marked up by another (who most probably shared Cicero’s

distaste for the form), texts were punctuated inconsistently or not

at all. Writing was, however, about to be well and truly shaken up

by the biggest upheaval since Rome’s fall from Republic to Empire.

The emergence of Christianity a scant few decades after Jesus’s death

would change the face of written language on a grand scale, and almost

as an afterthought, it would kick-start the pilcrow’s journey from К

for kaput to a fully formed mark in its own right.

7 tV и

- H,; V V ^

* •' ■'/ s -r ,y \ • ‘ .

хЩШЙтніЯХІ JV71.VJ i fc*

It Figure 1.3 Third line at left: К for kaput, set off by a dot on either

side, signaling the “head” of an argument, in a copy of Cicero’s In Verrem

from the first century bc/ad.