4 SHADY CHARACTERS

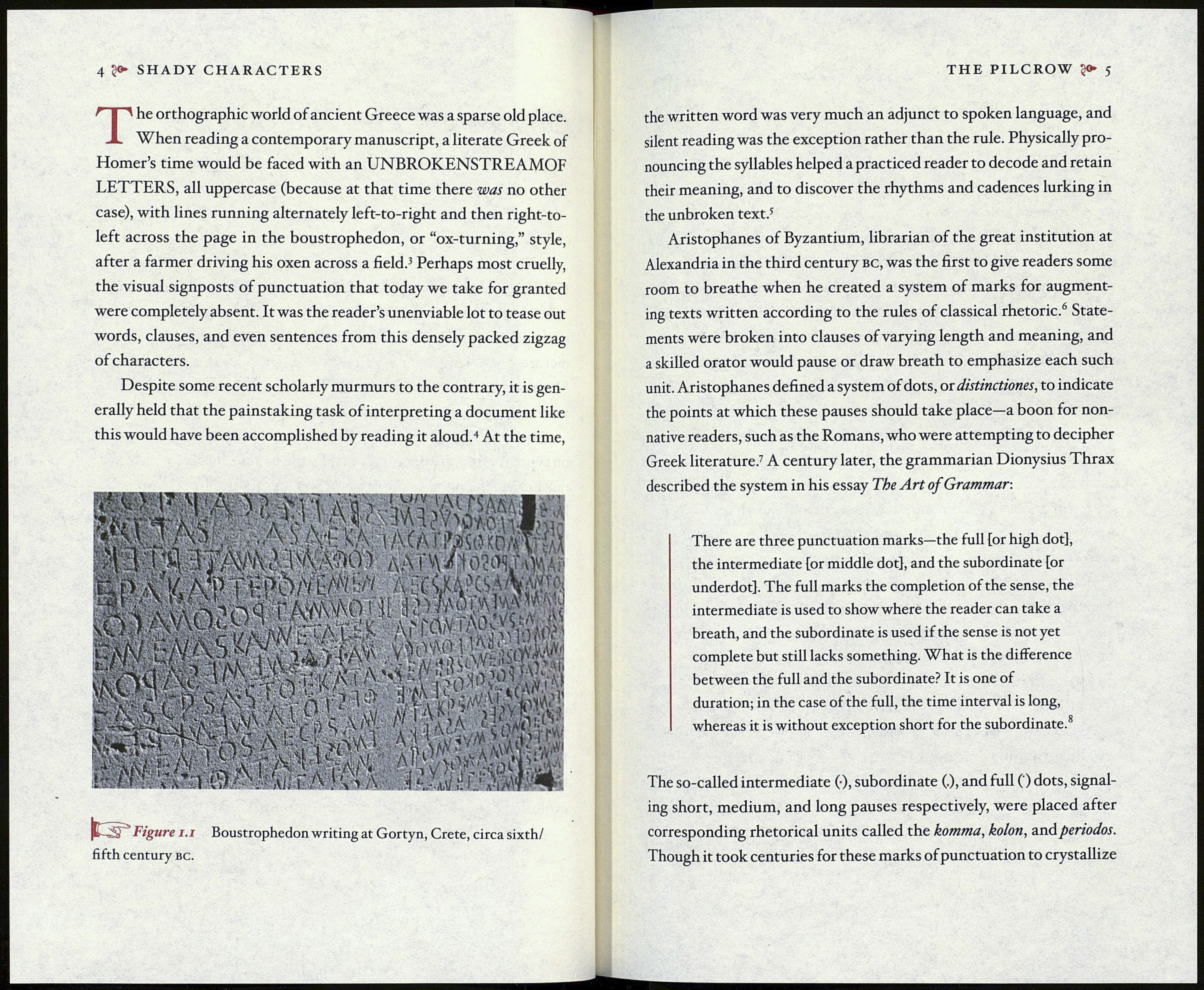

The orthographic world of ancient Greece was a sparse old place.

When reading a contemporary manuscript, a literate Greek of

Homer’s time would be faced with an UNBROKENSTREAMOF

LETTERS, all uppercase (because at that time there was no other

case), with lines running alternately left-to-right and then right-to-

left across the page in the boustrophedon, or “ox-turning,” style,

after a farmer driving his oxen across a field.3 Perhaps most cruelly,

the visual signposts of punctuation that today we take for granted

were completely absent. It was the reader’s unenviable lot to tease out

words, clauses, and even sentences from this densely packed zigzag

of characters.

Despite some recent scholarly murmurs to the contrary, it is gen¬

erally held that the painstaking task of interpreting a document like

this would have been accomplished by reading it aloud.4 At the time,

'■мѵтт

Ш,||

Щ&Й

^ Figure 1.1 Boustrophedon writing at Gortyn, Crete, circa sixth/

fifth century вс.

THE PILCROW 5

the written word was very much an adjunct to spoken language, and

silent reading was the exception rather than the rule. Physically pro¬

nouncing the syllables helped a practiced reader to decode and retain

their meaning, and to discover the rhythms and cadences lurking in

the unbroken text.5

Aristophanes of Byzantium, librarian of the great institution at

Alexandria in the third century вс, was the first to give readers some

room to breathe when he created a system of marks for augment¬

ing texts written according to the rules of classical rhetoric.6 State¬

ments were broken into clauses of varying length and meaning, and

a skilled orator would pause or draw breath to emphasize each such

unit. Aristophanes defined a system of dots, oxdistinctiones, to indicate

the points at which these pauses should take place—a boon for non¬

native readers, such as the Romans, who were attempting to decipher

Greek literature.7 A century later, the grammarian Dionysius Thrax

described the system in his essay The Art of Grammar-.

There are three punctuation marks—the full [or high dot},

the intermediate [or middle dot}, and the subordinate [or

underdot}. The full marks the completion of the sense, the

intermediate is used to show where the reader can take a

breath, and the subordinate is used if the sense is not yet

complete but still lacks something. What is the difference

between the full and the subordinate? It is one of

duration; in the case of the full, the time interval is long,

whereas it is without exception short for the subordinate.8

The so-called intermediate (•), subordinate (.), and full (') dots, signal¬

ing short, medium, and long pauses respectively, were placed after

corresponding rhetorical units called the komma, kolon, and periodos.

Though it took centuries for these marks of punctuation to crystallize