194 ?** SHADY CHARACTERS

have been singing from the same hymn sheet, so to speak, but they

could not agree on how to quote from it.

* * *

Even within the swelling corpus of Christian writing, the diple

occasionally took on roles beyond that of its traditional marker

of Biblical quotations. In one fifth-century manuscript entitled Apol¬

ogy Against Jerome,* Rufinus of Aquileia berated his onetime friend

and ally Saint Jerome for repudiating certain controversial beliefs

earlier espoused by Origen (he of Hexapla fame), having previ¬

ously supported them.24 The precise details of this theological spat

are beyond the scope of this book, but suffice it to say that then, as

now, flip-flopping was not admired, and Rufinus was incensed by

Jerome’s self-serving changes of heart. Taking care to distinguish

his own words from those of his craven opponent, Rufinus wrote in

his introduction that

in order that the insertions I am now making in this work

from elsewhere may cause no confusion to the reader, they

have single marks at the beginnings of the lines if they are

mine and double ones if they are my opponent’s.25

The mark Rufinus spoke ofwas the diple, deployed singly or doubled

UP ( - to distinguish between extracts from his own earlier works,

and those of Jerome.26 Though his was a Christian work, Rufinus’s

use of the diple was very much in the ancient, pagan Greek tradition,

♦ “Apologetics” usually referred to the intellectual defense of Christianity, but was also used

in the titles of many works written to prosecute theological debates between rival Christian

scholars and clerics.23

QUOTATION MARKS 595

even as he added a new layer of structure and meaning. In fact, those

readers who recall the early days of the Internet may find Rufinus’s

doubled diple familiar; the “Usenet” system of online bulletin boards

employed one or more right-pointing angle brackets (>, », »>, and

so on) at the start of quoted lines to indicate the level of the reply.27

For instance:

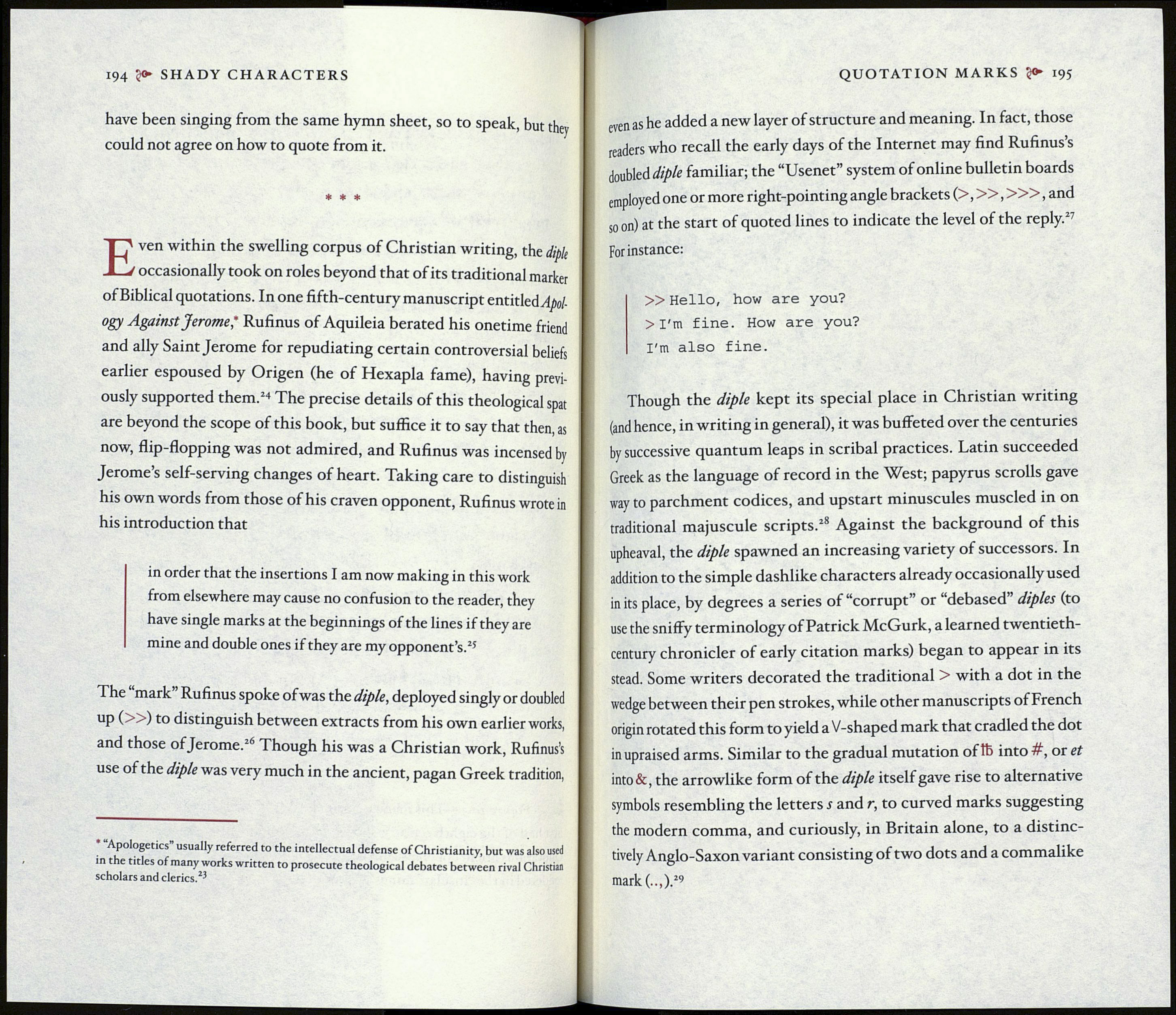

» Hello, how are you?

> I'm fine. How are you?

I'm also fine.

Though the diple kept its special place in Christian writing

(and hence, in writing in general), it was buffeted over the centuries

by successive quantum leaps in scribal practices. Latin succeeded

Greek as the language of record in the West; papyrus scrolls gave

way to parchment codices, and upstart minuscules muscled in on

traditional majuscule scripts.28 Against the background of this

upheaval, the diple spawned an increasing variety of successors. In

addition to the simple dashlike characters already occasionally used

in its place, by degrees a series of “corrupt” or debased diples (to

use the sniffy terminology of Patrick McGurk, a learned twentieth-

century chronicler of early citation marks) began to appear in its

stead. Some writers decorated the traditional > with a dot in the

wedge between their pen strokes, while other manuscripts of French

origin rotated this form to yield a V-shaped mark that cradled the dot

in upraised arms. Similar to the gradual mutation oftb into #, or et

into &, the arrowlike form of the diple itself gave rise to alternative

symbols resembling the letters s and r, to curved marks suggesting

the modern comma, and curiously, in Britain alone, to a distinc¬

tively Anglo-Saxon variant consisting of two dots and a commalike

mark(..,).29