8

HILARY MADDOCKS

finished translation to the Queen, Jeanne de Bourgogne. This iconography, used fre¬

quently in manuscripts illuminated by the Cité des Dames shop, flatters the owner

with a pointed reference to the royal patron of the original translation.27

While new iconography was derived from non-devotional manuscripts, the

principal source for additional illustrative material was the text of the Légende dorée

itself. The tendency to turn to the text is most marked in large, well organized shops

responsible for producing luxury manuscripts for demanding patrons. The illustra¬

tion of Voragine’s narrative presented a challenge for these artists because each text

entry was accompanied by only one frame. Techniques were devised like the repeat¬

ing of characters and the circular motion of the narrative used by the Chief Associate

of Maître François (BN ms fr. 245 f. 179v; Figure 8). This miniature illustrates the

life of St. Cecilia, and describes the conversion of her spouse, Valerian. In the left

foreground Cecilia bids Valerian to seek out the holy man Urban in the tombs of the

martyrs. He is pictured departing on his quest. In the background, the scene

encountered by Valerian is represented, complete with the water with which he is

subsequently baptized. On his return he recounts his experience to Cecilia and an

angel appears, crowning the couple with roses and lilies from Paradise. The figures

of Cecilia and Valerian in the left foreground are used again for this final episode so

completing the narrative circle. To clarify the sequence the artist has identified the

figures with labels and included a speech scroll.

Other methods of encompassing the narrative are not so complex, and involve

the juxtaposition of two or more different episodes. A miniature depicting St.

Euphemia (Pierpont Morgan MS M. 675, f. 90; Figure 9) is divided by a mound and

a church building into background and foreground. Behind, Euphemia withstands

torture on the wheel, while her attackers fall, overcome by flames. In the foreground

she resists the serpents who pull one of her enemies to his death. The final reward

for her faith is also represented—martyrdom, on this occasion by the sword.

The events represented in these pictures are based on a close reading of de

Vignay’s translation of the text. It could be argued that the interest in amplified nar¬

rative represented a move towards naturalistic or mimetic interpretation. The first

priority of the artists however, is to provide an illustration appropriate to the particu¬

lar saint’s life, and this is often inconsistent with an Albertian notion of naturalistic

representation. For instance, a hagiographie narrative is commonly represented by

the selective juxtaposition of two related or contrasting scenes which illustrate an

important lesson from the life of the saint for the faithful.

The miniature illustrating the narrative of St. Germain of Auxerre in a Légende

dorée in the Pierpont Morgan Library (MS M. 674, f. 357v; Figure 10), is not the

spatially and logically coherent picture it may seem at first. Within the walled city

of Auxerre at left, Germain, then Governor, is chastised by the Bishop, St. Amator,

for pride in his hunting and his habit of hanging the heads of slaughtered animals

Berry—The Limbourgs and their Contemporaries (New York: 1974) 7-18 and 377-378.

29 The significance of the author presentation portrait is discussed by Salter and Pearsall “Pictorial

Illustration... ”

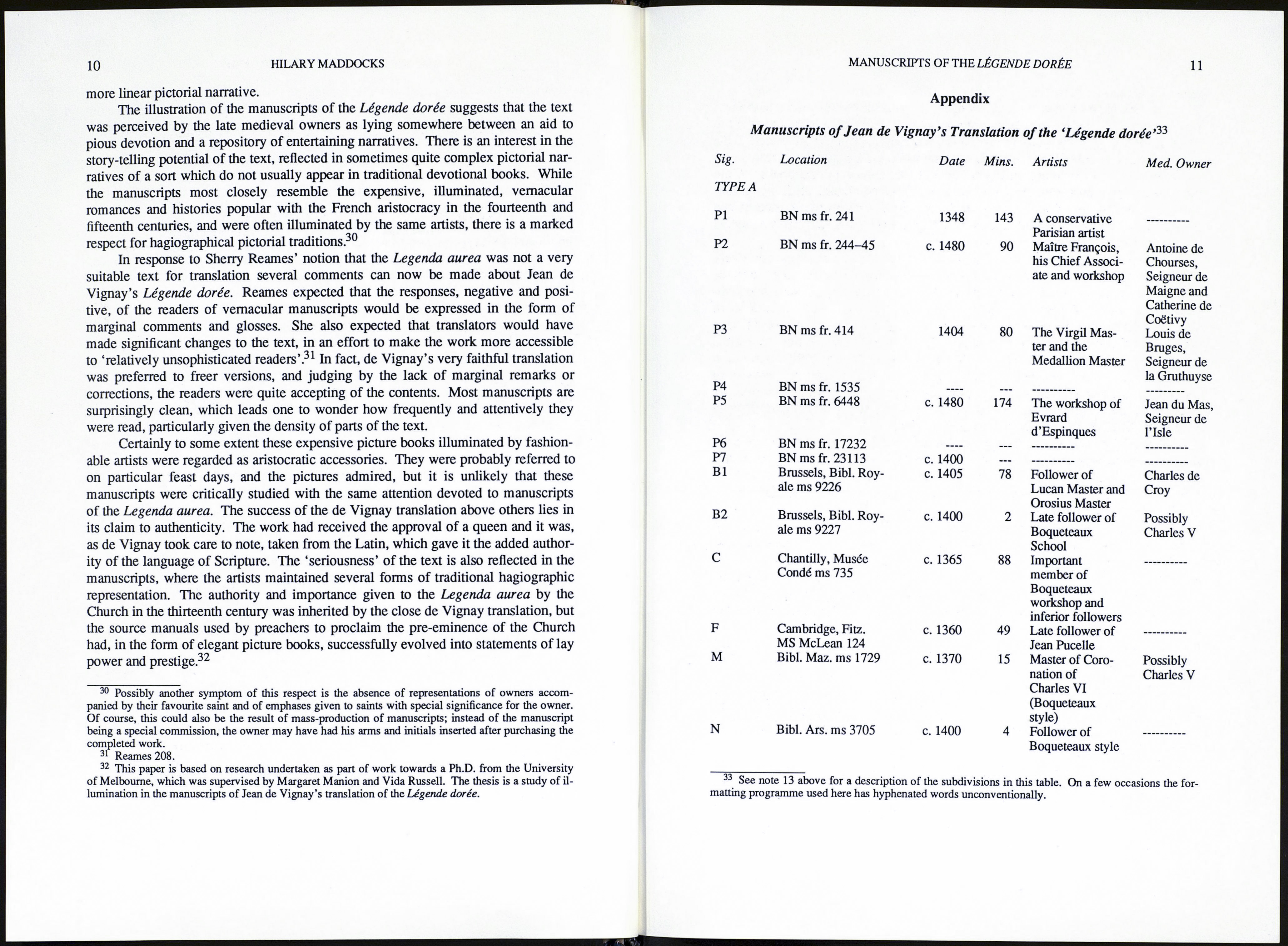

MANUSCRIPTS OF THE LÉGENDE DORÉE

9

from a pine tree. In contrast with this former life is Germain’s atonement and eleva¬

tion to the rank of Bishop of Auxerre, shown at right. The two halves of the picture

bear little mimetic relation to each other; the church is placed illogically outside the

city walls. On both sides the figures are disproportionate to the architectural set¬

tings. This diagrammatic as opposed to naturalistic quality is quite intentional on

the part of the artist. Similar juxtapositions which establish certain instructive rela¬

tionships appear in other hagiographie texts, such as in early medieval illustrations

from libelli, single narratives associated with the shrine of a saint28

Clearly the aristocratic readers of the Légende dorée placed some importance

on illustration in the manuscripts they owned. The Légende dorée is not unique in

this respect; apart from the many well-known examples of lavishly illuminated

Books of Hours, luxury illuminated manuscripts of original or recently translated

vernacular texts were the height of fashion among the French aristocracy. These

texts were usually romances, classical histories or chronicles, such as the famous

Roman de la rose, the Miroir historial by Vincent de Beauvais, the Histoire Anci¬

enne jusquá César, the Fleur des histoires, the Grandes Chroniques de France and

the Bible historíale. Like the Légende dorée, many of these texts were written or

translated for aristocratic patrons, and the manuscripts were usually illustrated.

Physically, these vernacular romances and histories were very similar to the

manuscripts of the Légende dorée. They were all usually very large, copiously illus¬

trated volumes, written in an elegant cursive hand in double columns, and decorated

by the same groups of artists. The illuminations often took the form of square mini¬

atures set into one column of text, except for larger miniatures introducing important

sections of the text.29 The hagiographie illustrations decorating histories like the

Miroir historial and the Grandes Chroniques de France tend to be rather more

detailed than those of the Légende dorée because often more than a single picture is

used to illustrate the life of a saint. The reason for this is the greater emphasis given

to the process of story-telling, and the value of the narrative as entertainment. The

folio divided into a series of six miniatures painted in the Boqueteaux style, which

illustrate the life of St. Louis in the Grandes Chroniques (BN ms fr. 2813 f. 265),

glorifies good deeds in the life of a great Frenchman. His birth, unremarkable in

itself, is followed by a depiction of his education and charitable works. The instruc¬

tive juxtapositions in the Légende dorée, which contrast states of ignorance and

grace or strength in torture and salvation through martyrdom, are not found in this

The small books known as libelli were attached to saints’ shrines and contained a description of

the life and miracles of the saint. Most date from the 11th and 12th centuries, and are associated with

the growth of the major abbeys. They played a role in promoting pilgrimage to the burial or resting

site in acting as an authentification of the saint. The miracles and martyrdom of the saint were often

demonstrated in juxtaposed pictures which clearly illustrated the transition from one state to another.

Several libelli are illustrated in J. Porcher, Medieval French Miniatures (New York: 1959) 12ff.

29 See M. Alison Stones, “Secular Manuscript Illumination in France,” Medieval Manuscripts and

Textual Criticism, ed C. Kleinhenz (Chapel Hill: 1976) 83—102, and E. Salter and D. Pearsall “Pictori¬

al Illustration . . .” Also relevant is Lesley Lawton, “The Illustration of Late Medieval Secular Texts,

with special reference to Lydgate’s Troy Book,” in Manuscripts and Readers in fifteenth Century Eng¬

land, ed. D. Pearsall (Bury St. Edmunds: 1983) 41-69.