IN THE BEGINNING.

nee upon a time,

all lettering was

hand-lettering. By

the nineteenth and

twentieth centur¬

ies, when type had

become cheap and

accessible to all,

the indicator of a

quality job was

that the logo, the

main display headline or the embellished ini¬

tial cap had been hand lettered, rather than

set in standard fonts that any competitor could

obtain for a few dollars.

ENTER TYPE, EXIT LETTERING

Up until about the mid-1960s—the dividing

line between the crew-cut conformist age and

the new age of inquiry—the majority of logos

and display headlines in magazines and ads

were hand lettered with brush or pen. The

changeover to a preference for type over letter¬

ing undoubtedly had something to do with the

emergence of huge photolettering type cata¬

logs by that time. But even Photo-Lettering,

Inc., maintained an active studio of hand let-

terers to tweak fonts for custom jobs.

As late as 1989, some agency hired me to

hand letter three words for a newspaper circu¬

lar ad. I thought they were nuts, since the style

they specified was almost identical to an exist¬

ing font. But they didn't want type, they want¬

ed unique, custom lettering exclusively theirs.

The tradition lives on today in the upper

echelons of publication design. You might look

at a logo and say, "But it's just Helvetica." No,

it's $20,000 worth of hand-lettered Helvetica

with a slight upturn added to the crossbar of

the lowercase e that justified the expenditure

and gladdened the heart of some CEO.

To this day, despite the computer revolution

that has loosed the font industry from its pig-

iron age moorings, type has yet to match the

limitlessness and flexibility of letters drawn by

hand where each letter shape can be nipped

and tucked to accommodate the surrounding

ones and every word or phrase can benefit

from the designer's maximal interpretation.

Because of the continuing glut of computer

fonts—the greater percentage of which are

embarrassingly amateurish—the idea of cus¬

tom lettering has lately been discarded along

with the 1.5MB floppy disk. This is fine for the

many and for those who don't mind using OPF

(other people's fonts) as the basis of their logos.

After all, the amazing number of fonts now in

existence, and the hundreds more that shall

emerge between the time of this writing and

its publication, might be said to provide a

measure of exclusivity to our work since most

people will never even be able to identify the

fonts we use.

But if you are designing an exclusive logo for

a company or a magazine masthead, would

you really want to use a font that anybody can

purchase for a few bucks or download for free?

Certainly, the owners of font foundries,

myself included, hope designers will continue

to buy our fonts for making logos. However, in

my other job, as a book writer, I'm the embodi¬

ment of the noble Chinese saying: "The extract

of the indigo plant is bluer than the plant

LOGO, FONT a LETTERING BIBLE

itself," which means, May the student swpass

the teacher. Of course, I hope you don't surpass

me, because I need to earn a living, too.

DESIGNERS DO IT WITH STYLE

The difference between a designer and an

actual artist is, a designer can indicate prefer¬

ences and arrange preexisting graphic ele¬

ments but cannot draw well enough to bring

his best visions to fruition by his own hand. A

designer's inability to draw may also uncon¬

sciously limit his ability to conceptualize.

Of course, lots of designers create incredible

pieces that make us all go, "Wow!" and want to

copy them. And since the end result is all that

matters, who cares if assistants do our creative

grunt work? The trendsetting designer Herb

Lubalin had letterers such as Tony DiSpigna

and Tom Carnase to bring his wonderful con¬

ceptions to fruition. Seymour Chwast, on the

other hand, despite the many designers he's

employed, has always kept his hand, literally,

in the work he produces.

"Today's designers," says letterer Gerard

Huerta, "are assemblers of stock images and

fonts. They learn how to assemble from source

books and put it all together, and they never

have to hire a photographer or illustrator,

because it's just a matter of assembling ready

made pieces."

It wasn't always this way. Many of the art

directors of old who hired the Norman

Rockwells and EG. Coopers of those times had

prodigious drawing and lettering skills. But

standards have fallen. Few of us today can

design, draw and letter the way guys like Will

Dwiggins, Walter Dorwin Teague, Clarence P.

Hornung and C.B. Falls did. (See "Letterers

Who Draw" on page 102.)

Throughout this book, I will try to create that

breakthrough for you, from being a designer

who specs type and pushes it around, to one

who creates type and then pushes it around.

You, too, can be like Frank Lloyd Wright, who

wrote, "Were architecture bricks, my hands

were in the mud of which bricks were made."

I will attempt to do this merely by convincing

you that you can do it—you've just been afraid

to try. Another reason you've relied on OPF is

that nobody ever told you the little secret that

I was privileged to have revealed to me by the

late, legendary cartoonist Wally Wood: "Never

draw what you can copy; never copy what you

can trace; never trace what you can photostat

and paste down." Nowadays, we'd say, "Never

trace what you can scan into Adobe

Photoshop." And there you have it; the secret to

becoming the logo designer you've always

wanted to be is: "Research."

THE PURPOSE OF THIS BOOK

/ wrote this book to enable you to expand

your creativity and end your reliance upon the

logos and fonts of other designers to become a

logo and font designer yourself. Of course,

there's nothing wrong with using OPF, espe¬

cially if you like them. I do it myself—con¬

stantly, as we all do at times—but won't you

feel proud when you can point to a logo or font

and say, "Look, Ma, I drew that... by hand!"

At this point I

should define the

terms hand-drawn

or hand-lettered not

just as letters we

create with drawing

tools on paper, but

also letters we cre¬

ate on computer,

because the hand

still guides the digi¬

tal tablet, mouse or

trackball. But the

important distinc¬

tion as far as this

book is concerned, as

to whether a logo or

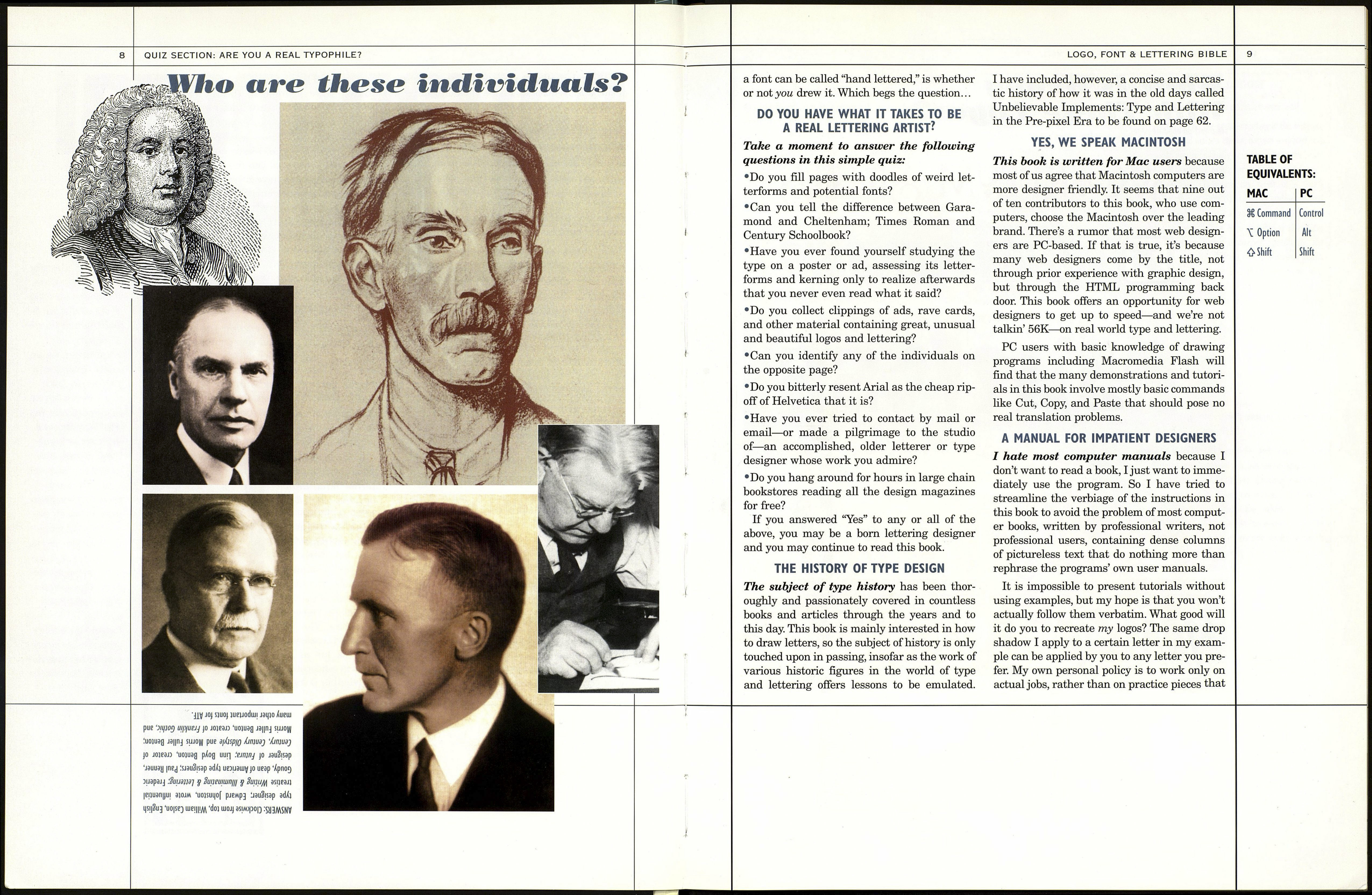

Paul Whiteman

The logo, font and lettering

samples in this book have

been liberally selected from

the past as well as from the

present. The basic principles

of typography never

become outdated, they just

reappear dressed up in con¬

temporary garb. Case in

point: In the past there was

the iconic bandleader, Paul

"Pops" Whiteman, and at

present we have Shepard

Fairey's ubiquitous Andre

the Giant logo, about which

he says, "The concept

behind 'Obey' is to provoke

people who typically com¬

plain about life's circum¬

stances but follow the path

of least resistance, to have

to confront their own obe¬

dience. 'Obey' is very sar¬

castic, a form of reverse

psychology."

Paul and Andre: two icons

separated by over seventy

years, and both leaders in

their fields. That's what I'm

talking about!