234

CLIENTS-----YA GOTTA LOVE 'EM!

'But I want my book cover in lots of colors,

not just blue, and I don't want these curly

flowers on the paper, either' So remem¬

ber, when it comes to rough comps, think

of them as sketches on a napkin."

Because computer roughs are so fin¬

ished-looking, we must explain to the

client that he is looking at roughs that

may not be used as final art.

One designer submitted logo

roughs on paper to a client who

decided to use one of them for

final art and assumed no fur¬

ther compensation to the

designer was required since she

was being saved the "extra work" of fin¬

ishing the logo.

This client didn't realize that if a

designer spits on a piece of paper and

that spit is used by the client, the

designer must be paid in full. If a com¬

pany goes ahead and uses an artist's

work inappropriately, the artist can

almost write her own ticket as to the

final billing for the illegal use (unless

the work was done under a WFH con¬

tract). But do everything possible to

avoid misunderstandings. Almost no¬

body wins in court, except lawyers.

MY CLIENT, MY TEACHER

Clients can be really annoying. Either

they have no idea what they want, or

they'll be so specific about every dumb

detail that you'll feel like asking them,

"Then what do you need me for?" And the

answer is, they don't. Only they don't

know how to use Illustrator and Photo¬

shop, so they really just want you to be

their hands.

It is true that most clients—like all the

drivers on the road ahead of us—are

dummköpfe, but every so often, those

seemingly ridiculous, annoying little

changes have ended up improving the

piece. Often, the client's input actually

makes us look good. Countless times,

after I'd gotten past my resentment over

being forced to make a change I didn't

agree with, I'd realize that I'd lost objec¬

tivity and the client was right! After all,

even though the client isn't a designer,

he may possess basic judgment.

But then again, clients often make our

lives a living hell by changing everything

good that we've done, leaving us too

embarrassed to even want to sign the

piece. Jobs like that you just let go. You

write them off and deposit the check. The

next job you do can go into your portfolio.

PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT

It's fun to demonize clients, but

remember, they have to deal with us, too!

Are you the kind of designer who really

listens and takes notes on what the client

wants, does preliminary research, deliv¬

ers sketches by the agreed upon date,

cheerfully makes changes and finally

delivers the finish by deadline? Or are you

the kind of designer who treats assign¬

ments like school homework, gets flus¬

tered and frustrated, procrastinates, calls

the client with excuses, makes sketches

without heeding instructions, complains or

becomes belligerent about changes, and

makes the client leave messages for you

while you avoid him because you were par¬

tying instead of working?

The fact is, many deadlines are frivo¬

lous or false—the client may actually

have extra time—but we cannot operate

on that basis. Deadlines, especially for

publications, can be very tight and dead

serious. Many times, art directors confid¬

ed that we artists are notoriously unreli¬

able. I was also told, on several occa¬

sions, that the fact that I respected their

deadlines and got my work in on time

was one reason why they often hired me,

rather than someone else.

GETTING THE JOB DONE

Here's a typical scenario: you've just

negotiated the price and landed a logo

assignment from a small company.

Submit a bill for one-third the price of

the job. If the client seems reasonable

and trustworthy you can agree to bill the

total job at the end. Sometimes it's bet¬

ter to show faith in the client to build a

relationship, but it's still a gamble on

your part. Basically, the more expensive

and extensive the job, the more impor¬

tant it is to get up-front money: A web

site or brochure design, definitely; a logo

or small illustration, not necessarily.

After listening carefully, and taking

notes as to what the client wants, begin

throwing out some ideas to see if you're

both on the same page. If the client is set

on an idea that you hate (clients notori¬

ously come up with undrawable, non¬

graphic concepts), sketch it for him along

with some better ideas of your own. He

may be smart enough to recognize your

superior approach over his preconceived

idea. Also, at this time, find out what

size and dimensions the finished job must

be and if there are printing specifications

such as two-colors only, or six PMS spot

colors plus blind embossing.

Steep yourself in research to

discover the approaches taken

by similar companies, or study

comparable products, then

make your roughs. Invariably

you will love one or two of them

and present the rest as filler to

bulk up the presentation. Invariably the

client will like your least-favorite sketch,

but she'll ask you to change the colors or

to combine the type from one logo with

the graphic from another sketch.

Should the client hate all your sketch¬

es, but send you away to try again, ask

lots of questions first to get her to

explain in greater detail what she wants

using your rejected sketches as a jump¬

ing off point. My policy (though we all

hate when this happens) is to do one or

two more rounds of sketches until the

client is pleased. Otherwise we may lose

the job altogether. If after that she is

unpleasable, both parties will usually

decide to call it quits.

But let's say that the client likes your

next sketches and tells you to finish one

of them, which you do. Now submit your

second bill for the sketches (which usu¬

ally represents three-quarters of your

actual labor on any job). Finally, you

hand in the finish. The client looks at it

and says, "Great! Just what I wanted...

except... whattaya think if instead of two

cows as we agreed, make it two mules."

We must now decide whether to bill for

the change or to accept it graciously and

not be petty. Whether we do so or not will

depend upon the complexity of the

change (I usually do the first change for

free), whether the client has been a pain

in the behind, how many other changes

have been asked for during the process,

and whether or not we feel it worthwhile

absorbing the loss of time in order to

build a relationship with the client that

might lead to further work.

Let's make clear that there are two

types of changes: those the client asks

for before "signing off" (giving official

approval) on a sketch, and those changes

the client asks for when he changes his

If you disagree with a client, try to

give him what he should have,

rather than what he thinks he wants.

LOGO, FONT a LETTERING BIBLE

235

mind after we've done the job precisely

according to his wishes. In the first case,

we are obliged to make changes or we

may lose the job. In the second case, the

client should pay for our wasted time

when he can't make up his mind. Yet,

between the sketch and the finish there

can be a world of differences and the

client should have the right to tweak the

finish to his satisfaction—up to a point.

Unfortunately, the client can withhold

payment if he's not satisfied with the

final, so it's best to make nice-nice and

try to keep him happy because, in the

end, the customer—even when he's a

moron—is always right. Once the job is

finished and billed don't neglect to

request printed samples of the job for

your portfolio.

MARKETING FONTS

After we've designed a font, what then?

Most larger foundries accept outside sub¬

missions and have differing submission

guidelines that can be found on their web

sites, or by e-mailing them. Most

foundries will want fonts with full char¬

acter sets, though your first submitted

version won't need to be complete.

Some foundries pay advances although

that has become rare. Most often, you'll

receive a royalty the amounts of which

can vary widely, from 10 percent to 50

percent according to foundry. Online font

foundries seem to distribute fonts accord¬

ing to one of three principles: Sell high-

quality fonts at high prices, low-quali¬

ty fonts at low prices, or give 'em

away free.

I have taken many pot shots at free

font foundries because those of us

who sell our fonts, naturally don't

like the idea that our prices—and

some customers' senses of value—are

being undermined by fonts that are free.

If Pontiacs were given away free on the

web, many people would not want to pay

for a Lexus, even though the difference

in quality might be considerable. This

analogy is well applied to fonts. Not

always, but in general, the quality of free

fonts can't compare to that of profession¬

al fonts sold by the larger foundries. For

one thing, assuming most designers

need to eat, how many of us can afford to

work for free? Thus, the free fonts are

often those produced by students, retir¬

ees or others who often don't spend

enough quality time with their products

to tweak them to a professional level.

Regardless of whether you sell or give

away fonts, if you intend to do it yourself,

you'll need a web site. Ideally you'll be

able to include features like automatic

credit card billing and automatic down¬

loading so that font lovers in Australia

will not have to wait until you wake up to

receive their fonts. The best way to plan

your font site is to type "fonts" in a search

engine and research font sites as well as

font prices.

I, DESIGNAHOLIC

The Latin phrase "ars longa, vita bre-

vis" (art is long, life is short) sums up my

feeling that there's just too much to

accomplish and too little time to do it in.

When I was a boy, my mother used to say

to me, "Why don't you go outside and

play?" I'd answer, "What do you mean—

there's no pencil and paper out there!" Or

she'd say, 'You're always working!" And

I'd say, "I'm not working, I'm playing." And

that's how my life has gone, ever since.

Author James Michener wrote, "A mas¬

ter in the art of living draws no distinc¬

tion between work and play. He hardly

knows which is which. He simply pursues

his vision of excellence through whatever

he is doing and leaves others to deter¬

mine whether he is working or playing."

So I began to wonder if workaholism is

a prerequisite to greatness, if other

designers were like me, and if I should

tell my readers that you have to work

hard to get good at this. I sent a short

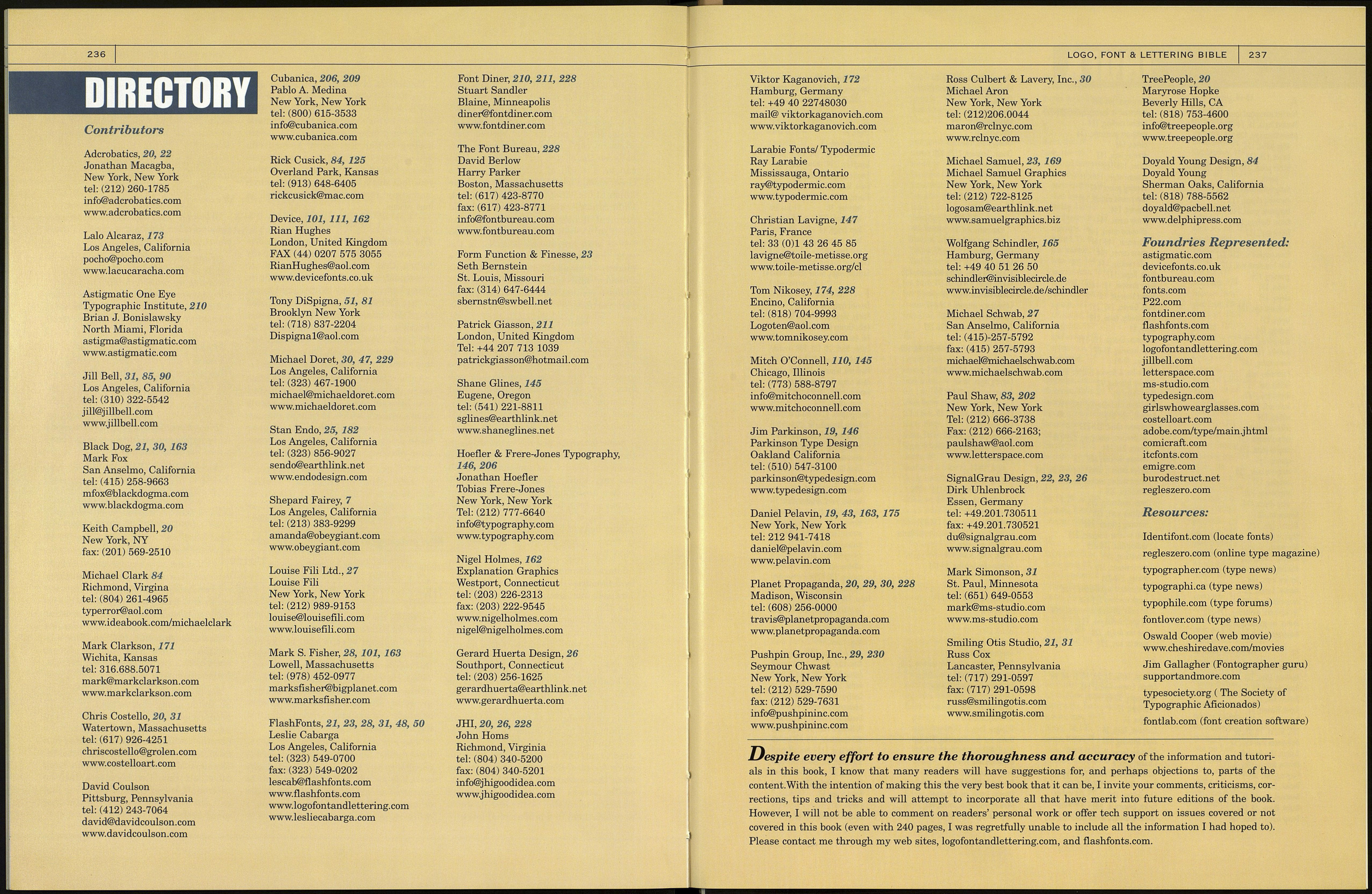

What percentage of waking hours do you spend:

Working

With spouse

/family

Hobbies

Recreation

On the

internet

71%

11%

2%

9%

7%

survey to the contributors of this book. I

asked for percentages of time spent work¬

ing, as opposed to time with family and

other activities. The following averages,

the result of twenty professionals sur¬

veyed, are revealing (see above). But more

interesting were the comments that

invariably accompanied the surveys some

of which I've included, without identify¬

ing the writers:

"There is never enough time to get the

work done. It always seems barely

enough, so any time that isn't specifically

set aside for the rest of life tends to be

converted to 'guilt time': I really should

be working. Because, for some reason, I

think my work is important."

"Your survey really shows me how

much my life sucks! I need to make some

significant changes, however, my mind

seems to need to remain consumed with

problems to solve and information to

absorb."

"Even while doing other stuff, I'm

always thinking about design I illustra¬

tion. Ideas will come to me from all kinds

of experiences and feed in."

"When I'm working, all I think about is

sex, and when I'm having sex, all I think

about is work."

"If the word 'working' includes design¬

ing as well as thinking, or 'pre-designing/

dreaming up projects, talking to potential

clients, seeking inspiration and other such

nebulous activities, mental and otherwise,

then 80-90 percent of my time is spent this

way."

"I have sacrificed much 'fun' time in my

life since I started working at a young age.

[Your survey results] really make me won¬

der if I should take more time for myself,

because my bank account certainly isn't

growing."

"If work paid about three times as well,

I'd be happy to do a little less of it. I can't

afford not to be insanely busy"

"Ahh, what a sad, sad life we type

designers live, all for the love of letters. I

wish I had time for hobbies."

"It is quite shocking to actually tally

the hours spent on work versus the

rest of life that includes family,

friends, socializing, etc."

"I'm not sure anyone who isn't born

with this affliction called 'creativity'

can really understand what it means

to live with the 'sweet & sour.' One

day art schools will require all prospec¬

tive graduates to complete a course called

'Insatiable Appetite 101' or 'The Un-

scratchable Itch.' I've had the disease

since birth... The blank page forever chal¬

lenges my pencil."

For myself, I have learned that there is

an ironic agony that follows an artist's

progression. The further we are able to

advance along the artistic path, the

greater becomes our ability to see just

how much farther the road extends.

Designer Michelangelo Buonarotti must

have felt this. On his death bed he

uttered, "I regret that...I am dying just

as I am beginning to learn the alphabet

of my profession."