-i82- American name for Koch's Locarno.) That suggests a type inten-

Some designers and ded for the text of advertising material for, say, a fashion house

their types or a hotel chain. But the type seems too decorative for anything

more than a line or two. There is another possibility. Griffith may

have told Dwiggins that Linotype did a steady trade with the

printers of wedding and other social stationery, and an alterna¬

tive to the well-known Card Italic and Lino Script would be

useful. Charter was an informal letter (except for e), upright but

suggestive of script, though the letters did not join. Only the

lowercase was made; trials of an ornamental 'Tuscan' T and V

and a script M were not taken further. In 1946 the type was given

a selective public showing in (surprisingly) book form - a limited

edition of Andrew Lang's Aucassin and Nicolete, produced by

the Golden Eagle Press at Mount Vernon, New York. In place of

the non-existent font capitals the small capitals of Electra were

used. The general effect is charming at first sight, affected at a

second view, and not very useful as a specimen of what was

obviously not a book type. Charter was never completed for sale

to the trade.

Soon after Dwiggins began his association with Linotype he

evidently felt that he should contribute to their activity in news¬

paper type designing. Griffith, who was much involved in the

development of variations of the Ionic type and anxious about

their commercial success, firmly asked him to stay away from

the subject. It was not until 1936, when the 'legibility group' of

newspaper text faces - Ionic, Textype, Excelsior, Opticon and

Paragon - were clearly on the way to dominating newspaper

typography in America (and, indeed, in most of the world), that

Griffith felt able to attend to Dwiggins's ideas and experiments.

But on this subject it appears that Dwiggins was able to say more

than he was able to perform. In a letter to Griffith in 1937 he

referred to Ionic and the derivatives as 'the first intelligent effort

in the line ever made . . . You have taken the style of letter est¬

ablished by custom as "the" newspaper face, and have modified

it step by step until it will print under modern conditions, and can

be read when printed . . . This style was taken over for historical

reasons. It was the style of type-letter in fashion when news¬

papers began their expansion after the Civil War, and when

Linotype began its career. There wasn't any other kind of letter to

work on, so far as body matter went. So, naturally, Linotype's

experiment fastened upon this style, and by so doing fixed it as

the only kind of type face proper for newspapers to use. The style

was (and is) a much-modified bastard descendent of an original

"Scotch modern". In its post-bellum form it was not what one

could call a highly legible face.' That was sound enough, and

Stanley Morison would have applauded it - having expressed

similar ideas (though not so well) when his Times Roman was

introduced five years before. Unfortunately, the implication in it

The captain was still prowling about

the deck. Hubbard heard him lift up

his voice in a hail, "Masthead, there!

Keep your wits about you!"

"Aye, aye, sir."

The poor devil of a lookout up there

was the most uncomfortable man in

the whole ship, Hubbard supposed,

without sympathy for him. It was in¬

teresting to note that the captain was

apparently a little uneasy still about

the possible appearance of British

ships. Peabody had brilliantly brought

the Delaware out to sea—the first

United States ship to run the blockade

was a touch of elaboration about his

gesture which conveyed exactly

enough contempt both for the cere¬

mony and for the first lieutenant to an¬

noy the latter intensely, and yet too

little to make the captain's clerk liable

to punishment under the naval regula¬

tions issued by command of the Presi¬

dent of the United States of America—

not even under that all-embracing reg¬

ulation which decided that "all other

faults, disorders and misdemeanors not

herein mentioned shall be punished ac¬

cording to the laws and customs in

such cases at sea." The young cub

-183-

The types

ofW. A. Dwiggins

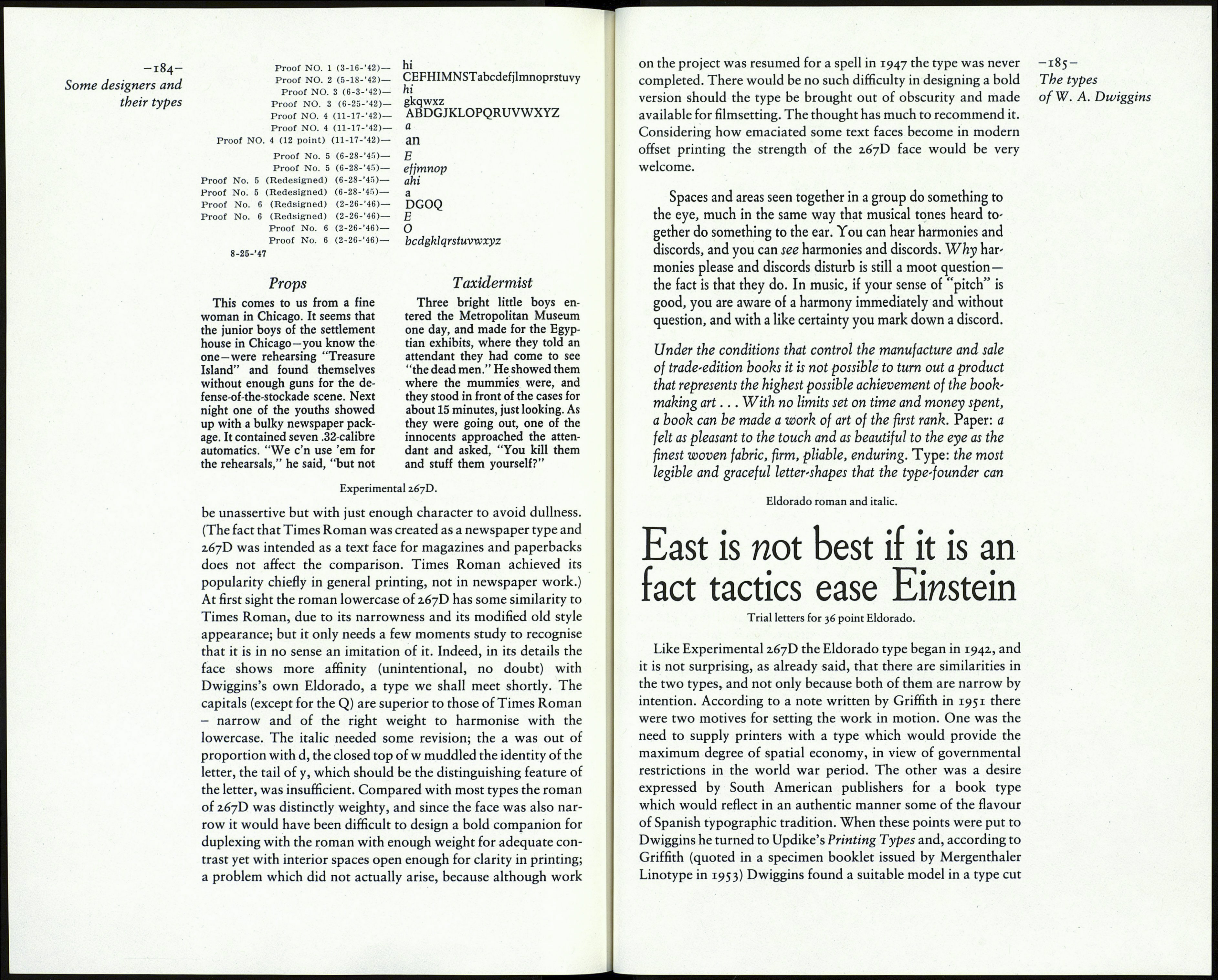

The Hingham experimental newspaper type, with Ionic capitals.

- that any alternative news face would have to arrive from an

entirely new direction — was not borne out by the result. In spite

of much experimental work, recently described in detail by

Gerard Unger, it looks as though Dwiggins was unable to put the

Ionic out of his mind, and could only think of altering its details.

In the event, the Hingham design was so much like the Ionic it

was meant to surpass that it is now chiefly interesting as evidence

that he was being allowed by Griffith (rather reluctantly, in this

case) to free-range over a wide area of typographic possibilities.

(As it happened, it was Griffith himself who carried the design of

newspaper text types to a new level, with the Corona face of

1941.)

A design not mentioned in Bennett's Postscripts and never

named - it was known only by its factory number Experimental

267D - is a type of particular interest, for several reasons. In

February 1942 Griffith sent Dwiggins a number of working

drawings for study purposes, including a projection of a letter

of 9 point Times Roman; and in a covering note he said, 'On the

whole I think we have made a sound approach to the original

problem of finding a face with the reading qualities of Bookman

and a style somewhere in the region of Caledonia and Times

Roman.' Plantin must also have been in their minds, because later

in that year Griffith thanked Dwiggins for his analysis of the type

and himself remarked on its 'dry and "engineery" effect'. But it

seems to have been Times Roman that concerned them most.

(Griffith was occupied in supervising the production of Times

Roman for the Crowell-Collier company which adopted the face

for the text of its magazines at the end of 1942 in a considerable

flutter of publicity.) Dwiggins referred to 267D in a letter in

December 1943: 'I was always sorry that it had to be laid aside to

make way for the Times Roman cutting, because I think it is a

better reading letter than T R and more useful. As a matter of fact

it is one of the most successful designs in our list, right through

the alphabet . . .'

I think he was right; 267D was potentially a much more

attractive and effective type than Times Roman - plain enough to