-178- him a regular retaining fee, payment for the designs he supplied,

Some designers and and a guarantee to make punches and matrices of any trial design

their types he sent in; and on his part, to create for the company type faces of

commercial application and promise (that they would be of high

quality could be taken for granted). Thus began an association

which lasted twenty-seven years and resulted in twelve type de¬

signs (not eleven, as Paul Bennett has said), though only five were

actually made available to the trade. Dwiggins's associate in the

work ('partner' would be more appropriate) was C. H. Griffith,

who had started in Linotype in 1906 as a salesman, graduated to

assistant to the president and, about the time under discussion,

became responsible for the company's typographic development.

Dwiggins now had to use his experience in lettering for advertis¬

ing to formulate ideas about letters for printing. Griffith had to

learn to understand the characteristics of the designs which

Dwiggins put forward; to supervise their manufacture, in which

he was able to rely on the experienced eye of Nils Larsen, head of

Linotype's type drawing office; and to evaluate the faces in dis¬

cussion with Dwiggins. The two men educated each other. Their

correspondence, with many drawings and type proofs, is pre¬

served at the University of Kentucky. If this were a full biograph¬

ical study of Dwiggins it would be necessary to make a thorough

examination of the Kentucky archive; but the chief purpose here

is simply to make a personal appraisal of his type designs, and

fortunately proof sheets and other specimens are at hand.

In the early 1930s the Linotype drawing office and matrix-making

plant in New York were occupied with the Granjon and Janson

book types, the Textype and Excelsior newspaper faces, and the

Poster Bodoni type for display purposes. Dwiggins himself was

busy with his book designing. So it is not surprising that their

working arrangement took time to reveal itself. Two years

passed before there was any sign of Dwiggins's second type, in

the form of trial characters; and it was 1935 when it was intro¬

duced to the printing trade. Electra, as it was called, was a book

type. Rudolph Ruzicka, writing in 1948, described it as 'the crys¬

tallization of his [Dwiggins's] own calligraphic hand. Though

highly disciplined, the pen hand is still revealed in the flick of the

weighted horizontal serif, in the finial of the lowercase с and

other subtle accents, and in the sweep of the curves generally.' It

is not easy to accept that as a description of the Electra roman,

where the discipline is much more evident than the calligraphy.

But it must be said that Ruzicka was echoing what Dwiggins

himself had written in the specimen booklet which introduced

Electra to the public: 'The weighted top serifs of the straight

letters of the lowercase: that is a thing that occurs when you are

making formal letters with a pen, writing quickly. And the flat

way the curves get away from the straight stems: that is a speed

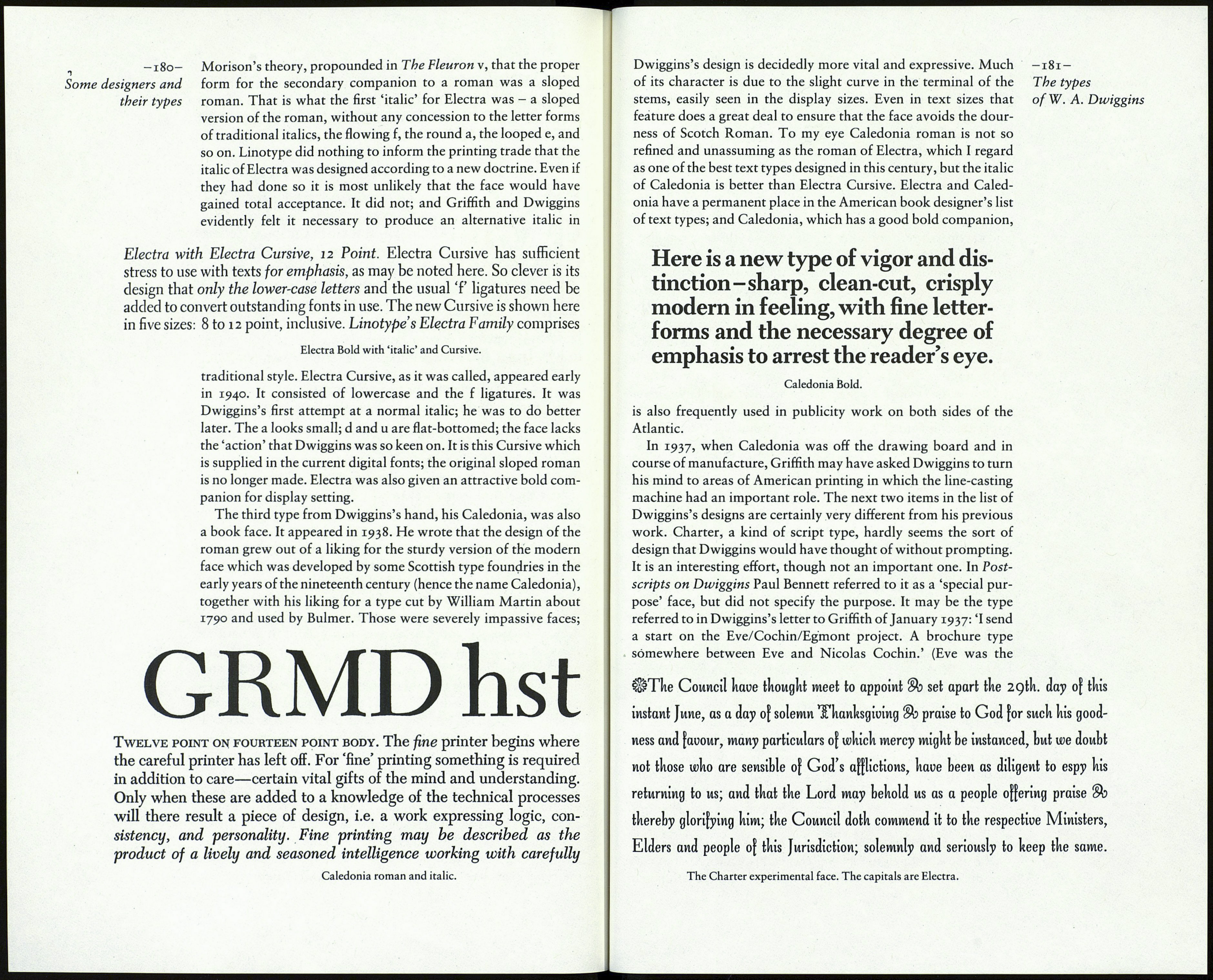

CHAPTER I

THE AUTHOR GIVETH SOME ACCOUNT OF HIM¬

SELF AND FAMILY; HIS FIRST INDUCEMENTS TO

TRAVEL. HE IS SHIPWRECKED, AND SWIMS FOR

HIS LIFE; GETS SAFE ON SHOAR IN THE COUN¬

TRY OF LILLIPUT; IS MADE A PRISONER, AND

CARRIED UP THE COUNTRY.

y father had a small Estate in Not¬

tinghamshire; I was the Third of five

Sons. He sent me to Emanuel-College

in Cambridge, at Fourteen Years old,

where I resided three Years, and ap¬

plied my self close to my Studies: But

the Charge of maintaining me (al-

«РС^Ча ^lb»0oNí¿2 though I had a very scanty Allowance)

being too great for a narrow Fortune, I was bound Apprentice

to Mr. James Bates, an eminent Surgeon in London, with

-----Nee si miserum Fortuna Sinonem

Finxit, vanum etiam, mendacemque improba finget.

Electra roman and italic.

product.' In such a context Ruzicka and Dwiggins were not very

precise in using the terms 'calligraphy' and 'writing', which

strictly mean the forming of letters by the flowing action of a pen,

held at an unchanging angle. A better word would have been

'lettering', meaning the drawing of letters, the pen or brush being

lifted and angled at each stroke so as to achieve a particular

modelling and style. Here and there in Electra it is possible to see

a resemblance to the lettering in the simulated advertisements

with which Dwiggins illustrated his Layout in Advertising. But

the fact is, to describe the Electra roman in terms of calligraphy or

drawn lettering is more misleading than helpful. It is hard to

think of any twentieth-century book type plainer and less ex¬

pressive than Electra. But it is not faceless: it has character and

distinction, the result of unobtrusive features like the unbrack-

eted serifs, the flat arches of m and n, the refinement of R, the

modelling of a and g. In American book production it ranks as a

modern classic. In Britain four sizes of the roman with italic had

been made when the outbreak of the Second World War brought

the work to a halt; it was not resumed when the war ceased. The

absence of some necessary sizes, and of the cursive, prevented

Electra gaining favour in Britain. Some typographers were un¬

aware of its existence until it appeared in filmsetting catalogues.

Dwiggins and Griffith were familiar with the writings of Stan¬

ley Morison, and a study of their personal papers might support

the belief that, like Jan van Krimpen, they were impressed by