-174- that owes its characteristics to a tool, such as pen or brush scripts.

Some designers and Indeed, some may say that the only logical design tool today is the

their types light pen or the cursor spot on a display screen. Perhaps we must

wait for the day when vectorising is an automatic process, editing

is unnecessary, and the result is a true facsimile. When the

designer's work can be reproduced directly and with complete

fidelity, without any sort of doctoring, we may hope to see, just

occasionally, type faces with something of the originality and

craftsmanlike quality that were Koch's particular contribution to

twentieth-century type design.

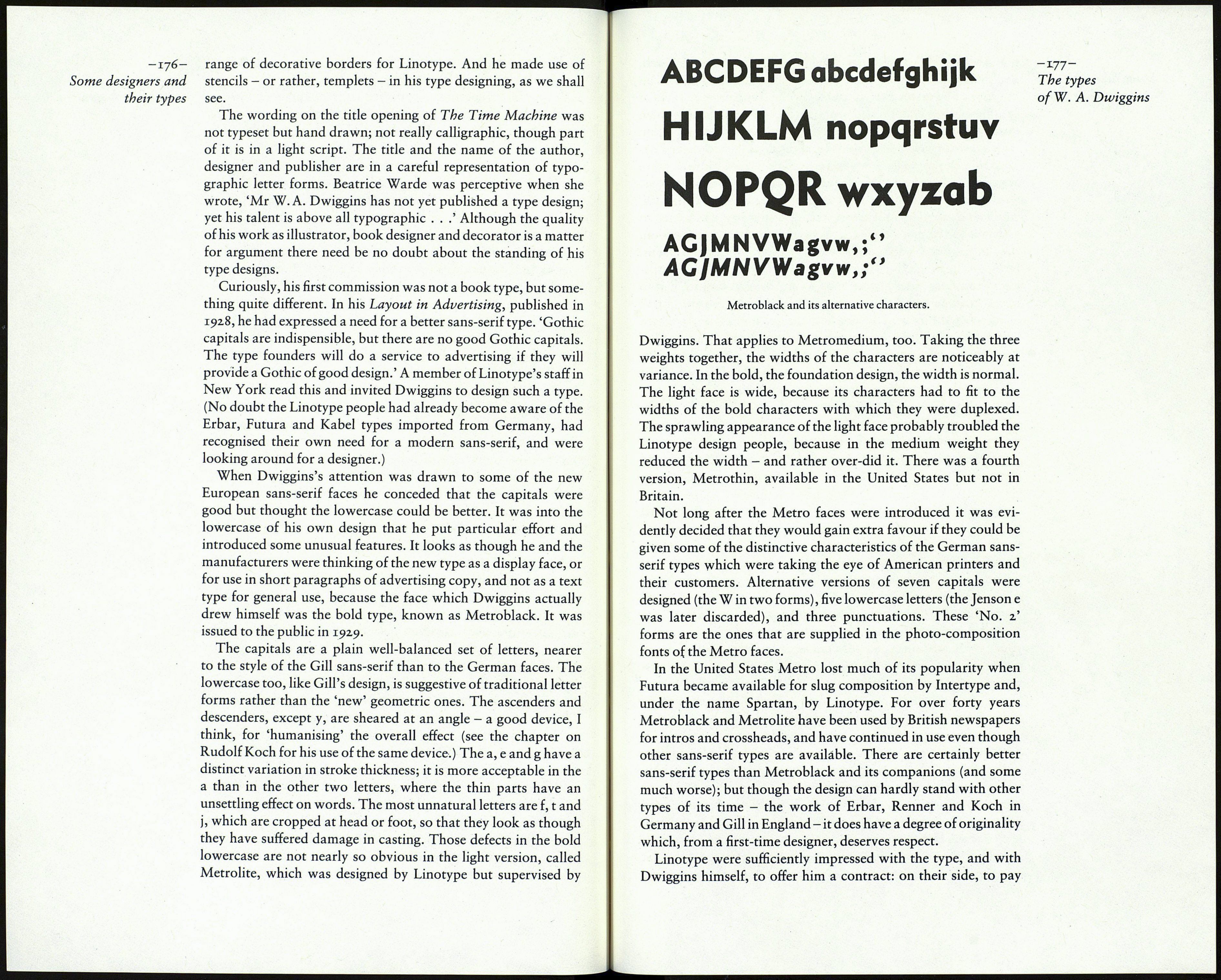

l6: The types of W. A.Dwiggins

Of the five designers whose work is discussed in these pages

W. A. Dwiggins is the one who most closely engaged himself

with the manufacturing processes of type faces for mechanical

composition, accepted their limitations and made use of their

possibilities. He is the only American designer to create a sans-

serif type of any merit; he created one of the best book romans of

the twentieth century, and also one of the most popular; and he

produced a number of designs which, though they were not put

on the market, are of considerable interest, and some would have

been a positive asset to the printer.

Dwiggins's career is as well known to the American typo¬

grapher as is Goudy's. In Britain his work is not so well known,

though his Metro type has been a constant favourite in British

newspaper printing for over forty years, and his Caledonia is

frequently seen in the text of modern publicity matter.

William Addison Dwiggins was born in Martinsville, Ohio, in

1880, the son of a doctor. At the age of nineteen he moved to

Chicago to study art at the Frank Holme School of Illustration.

He met Goudy there, became interested in lettering, and did some

miscellaneous work for advertisers. In 1903 he removed to Cam¬

bridge, Ohio, and started a small printing office, but it proved

inadequate as a means of making a living. When Goudy announ¬

ced his intention to move east to Hingham, Massachusetts, in

1904, and invited Dwiggins and his wife to join in the venture,

Dwiggins agreed, and lived there until his death in 1956. For his

first twenty years or so there he had a successful career as a

designer and illustrator in advertising. Amongst much else he did

some work for a music publisher in close imitation of the

elaborate cartouches to be seen in French and Italian engravings

of the second half of the seventeenth century. It has been said that

he had a liking for the chinoiserie fantasies of Jean Pillement, a

predilection which sometimes shows itself in the head and tail -175-

pieces he used in his book work. The types

By 1928 he had become dissatisfied with the ephemeral nature ofW. A. Dwiggins

of publicity work, and he decided to concentrate on the designing

and illustrating of books. He had already met Alfred Knopf, the

eminent publisher of the Borzoi titles, for whom Dwiggins

eventually designed nearly three hundred books. In 1932 he de¬

signed and illustrated Daudet's Tartarin of Tarascón for the

Limited Editions Club, and he was responsible for a further seven

books for that distinguished imprint before his death. He worked

for Random House, the Lakeside Press and other publishers of

note, and gained a considerable reputation in that field.

In regard to the illustrating of books Joseph Blumenthal, the

eminent American printer, has expressed an interesting view. 'As

a general rule I do not believe in book illustration . . .Illustration

in the literal sense can only portray, at best, the artist's personal

view of the text.' But suppose the artist's mind is in perfect accord

with the author's, as, for example, George Cruikshank's was

with Dickens's: is not the reader's enjoyment of the writer's work

immensely increased? I think so. Applying that criterion to the

limited amount of Dwiggins's book work I have seen, I do won¬

der if his reputation was wholly justified. To me his drawings

lack vitality, and his line is not expressive. Added to that, his

amiable cast of mind, which by all accounts made him a very

agreeable man to know, may have prevented him from respond¬

ing fully to some of the literature he was asked to illustrate. For

instance, in his treatment of Gulliver's Travels for the Peter

Pauper Press he loaded the book with devices and images quite

alien to the spirit of Swift's satire, and not at all interesting in

themselves. His double-page title for the Random House edition

of The Time Machine (1931) has been much admired; but it

seems to me to be entirely out of touch with Wells's bleak fable of

the end of all life, and to be no more than a self-indulgent display

of ill-arranged and disparate elements. Some of them are the

decorative units which he assembled from home-made celluloid

stencils. Beatrice Warde, writing as 'Paul Beaujon' in 1928, made

much of these, and quoted Dwiggins about them: 'The thing is

not to draw the working machine, but the curve that is in the

mind of the engineer before he designs the thing.' That is just

fancy talk, and would have brought an emphatic comment from

the engineers I used to know. Some of the stencil units are arcs of

various sizes and thicknesses, drawn with a compass; others are

simplified leaf shapes; some are geometric forms. With these, and

with lines and shapes added for the occasion, he would produce

two-dimensional constructions suggestive of plants or buildings,

or abstractions like the work we now call art deco. Their novelty

is undeniable, and they evidently charmed the publishers of the

time. Later on he used the stencil technique to create an attractive