Kabel light.

'Construction' grid letters from the Kabel specimen.

Both Neudorffer (see preceding page) and Koch probably drew

their letters without constraint, and 'rationalised' them afterwards.

and to each other. The explanatory text speaks of the great

variety of letter widths which can be made from a straight line at

various angles, circles large and small, and sections of them. This

variety of widths, says the text, is stimulating to the reader; it was

always understood in the past, but recently the designers of 'grot¬

esques' have regulated the widths of capitals and produced a

monotonous effect unsuited to today's needs. It all looks as

though there is a module, the square divided into a certain num¬

ber of vertical parts, and that the width of the capitals is deter¬

mined by it. But it does not take long to discern that the square is

not really the controlling element in the diagrams: that the widths

of B, D and U have been decided visually, not geometrically, and

that the diagrams are simply an attractive piece of window dress¬

ing to influence people into accepting Kabel as a rational design.

But Koch was evidently not a man to be bound by arbitrary rules.

In Kabel Light the arms of E are actually of three different

lengths; the bowl of R is deeper than that of B, and in P it is deeper

still; the U has a full-length vertical at the right; and Y does not

have the vertical stem shown in the diagram. In short, Koch's

sense of style is in command, rather than any geometric formula.

The result is an alphabet of capitals that relate perfectly without

need of the 'mathematical harmony' that Moholy-Nagy spoke

of. They are, for my taste, the most attractive of all sans-serif

capitals.

The lowercase is not quite so pleasing. The x-height is little

more than half the height of the ascenders, which certainly makes

The firm, the enduring, the simple

and the modest are near to virtue

THAT IS THE QUESTION

for a pleasant effect in text sizes. But there are some unfortunate -171-

letter shapes. The narrowness of m is very noticeable against Three types

round letters. The w is too wide for h, and looks awkward in the by Rudolf Koch

'wh' association which is frequent in English words. There are

wayward details in some letters: the shortened bar in f (t is better

looking), the inadequate ear on r, the cropped head of a - though

in later specimens an a with a wider top made an unannounced

appearance in some sizes of some of the faces of the family. Most

particularly, there is the excessive angle of the bar in the e.

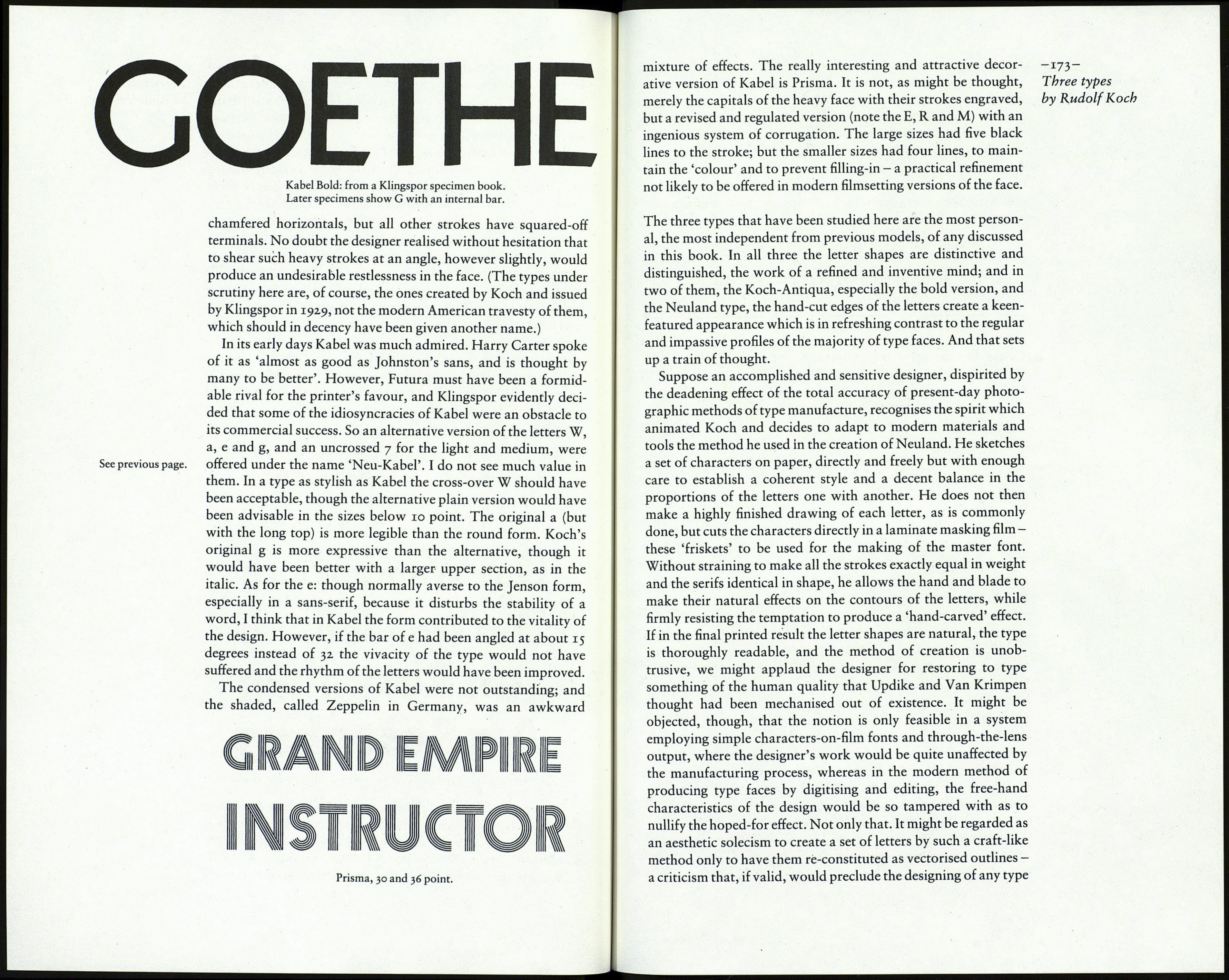

The medium weight of Kabel also shows those obtrusive char¬

acteristics; but the bold version (actually hardly more than semi-

bold) has some interesting differences. There are changes in

proportion: for instance, the D - see the specimen below on this

page - is wider, and the r and some other lowercase letters are in

better relationship. Only the e is a disturbing character, too 'ac¬

tive' for this class of design. The sheared terminals of the straight

strokes, clearly visible on the H in the specimen overleaf - a

feature which owes nothing to geometry - ingeniously increase

the liveliness of the design. (As noted earlier, Eric Gill wanted to

do something like it in the descender characters of his sans-serif

type, but was dissuaded. Dwiggins had the same idea, and got

away with it.)

Della stessa famiglia del primo premio,idue lavori

IL RISORGIMENTO GRAFICO 12345678

Dellastessa famiglio del primo premio,idue lavori

IL RISORGIMENTO GRAFICO 12345678

Das Wanderbuch

Das Wanderbuch

Am Rosenhag

Am Rosenhag

Kabel medium, bold and heavy, showing the alternative characters.

The heavy version is different again. Because of the consi¬

derable increase in weight (the strokes are about 75 per cent

thicker than those of the bold version) the lowercase x-height

is necessarily larger. Several letters have a new shape: A, M, R,

S, W and a are notable. The E, F, L and T retain the distinctive