-і2б- in the same year; no. 4 ten years later; no. 5 in 1927; and no. 6 in

Some designers and 1934. They are fine examples of page design and typesetting, and

their types desirable collectors' pieces.

Goudy seems to have enjoyed writing. The Alphabet, pub¬

lished in 1918, and Elements of Lettering, 1922 (they were later

issued in one volume), are not great works of scholarship, and the

latter, which was severely criticised by Stanley Morison in the

first volume of The Fleuron, does place too much attention on

Goudy's own type designs. But they are worth reading, so long as

they are not regarded as the only necessary source of inform¬

ation. Goudy also edited the first four numbers of Ars Typo¬

graphic, a 'quarterly' of high standing, and he contributed

articles to many periodicals for most of his life.

By 1920 he had nearly forty type designs on record, and his

reputation was high. In that year he was appointed 'art adviser'

to the Lanston Monotype Company of Philadelphia. The first

type he designed for them in that role (but not the first of his types

they had produced) was the Garamont roman, which was, like

most of the other versions of the caractères de l'Université, a

notable commercial success - though, as Goudy wrote, it 'was

not the result of inspiration or genius on my part . . .'

In 1925 he moved to Deepdene near Marlborough in New

York state, and established the Village Press and letter foundry in

an old mill, one of his recent acquisitions being the Albion hand

press on which the Kelmscott Chaucer had been printed many

years before (it had had several distinguished owners since

Morris).

When the Pabst Italic was in production in 1903 Goudy had

been interested to watch the matrices for it being engraved by

Robert Wiebking in Chicago. They became firm friends, and

Wiebking made the matrices for all Goudy's types, except those

designed for Monotype, until 1925. Wiebking died two years

later. Goudy decided to learn the craft himself:'. . . I attempted,

with no previous type-founding experience or tutelage under any

master, to learn every detail of type founding - making patterns,

grinding cutting tools, engraving matrices - after I had passed my

sixtieth birthday.' Most of the sixty-odd types he created from

1925 onward were in the fullest sense produced by his own hands.

The loss of the sight in one eye did not deter him; in fact, the next

twelve years were his most prolific period.

Disaster overtook him once again: '. . . suddenly, on the early

morning of January 26,1939, fire took from me the equipment so

laboriously got together, the hundreds of drawings, master and

work patterns, fifteen or twenty designs for types in process of

production - all gone. It was a body blow.'

A fund was raised to help him start again. It enabled him to

build a small studio in which he could write and draw in comfort;

but he could not obtain machine tools for matrix engraving until

1941, when the University of Syracuse lent him some equipment, -127-

and he was able to resume his type designing in the thorough- Some types

going way he preferred. He continued work until 1944 - long by Frederic Goudy

after he had been described as 'veteran' by a reviewer in The

Fleuron in 1930.

Admiration for his work was not limited to the printing trade.

As early as 1904 he was awarded a medal for book printing at the

Lousiana Purchase exposition in St Louis; in 1922 the American

Institute of Architects awarded him their craftsmanship gold

medal; and there were others. In 1920 he received the gold medal

of the American Institute of Graphic Arts, and there were honor¬

ary degrees and other awards from several universities. He

wrote, with some feeling, in the introduction to his Half-

Century, '. . . I am constrained to acknowledge here that I have

always deplored the fact that the first real recognition of my types

came from an English writer [he was probably thinking of Stan¬

ley Morison's praise of Goudy Modern] and English printers [he

may have meant Francis Meynell, who added Kennerley and

Forum to the equipment of the Pelican Press, and possibly also

George W. Jones, who commissioned a type from him], instead

of from printers and writers in my own fatherland . . .' But he

was being less than fair to his compatriots and overgenerous to

the English, who have been indifferent to (or perhaps ignorant.of)

most of his work as a designer and as a beneficent influence on

American printing for the larger part of the twentieth century.

Goudy's A Half-Century of Type Design and Typography,

which will often be quoted here, was written for The Typophiles

in 1943 and 1944. It is his personal account of the origins of his

types and his opinion of them. It is certainly fascinating; but

it must be said that it is not altogether satisfactory. He was

approaching eighty when he wrote it, not in the best of health,

and he may not have had total recall. Or he may simply have felt

entitled to be reticent whenever he wished. Whatever the reason,

there are places in the work where the information he gives is less

than adequate, and I have supplemented it with a speculation of

my own where it seems helpful to the understanding of a design.

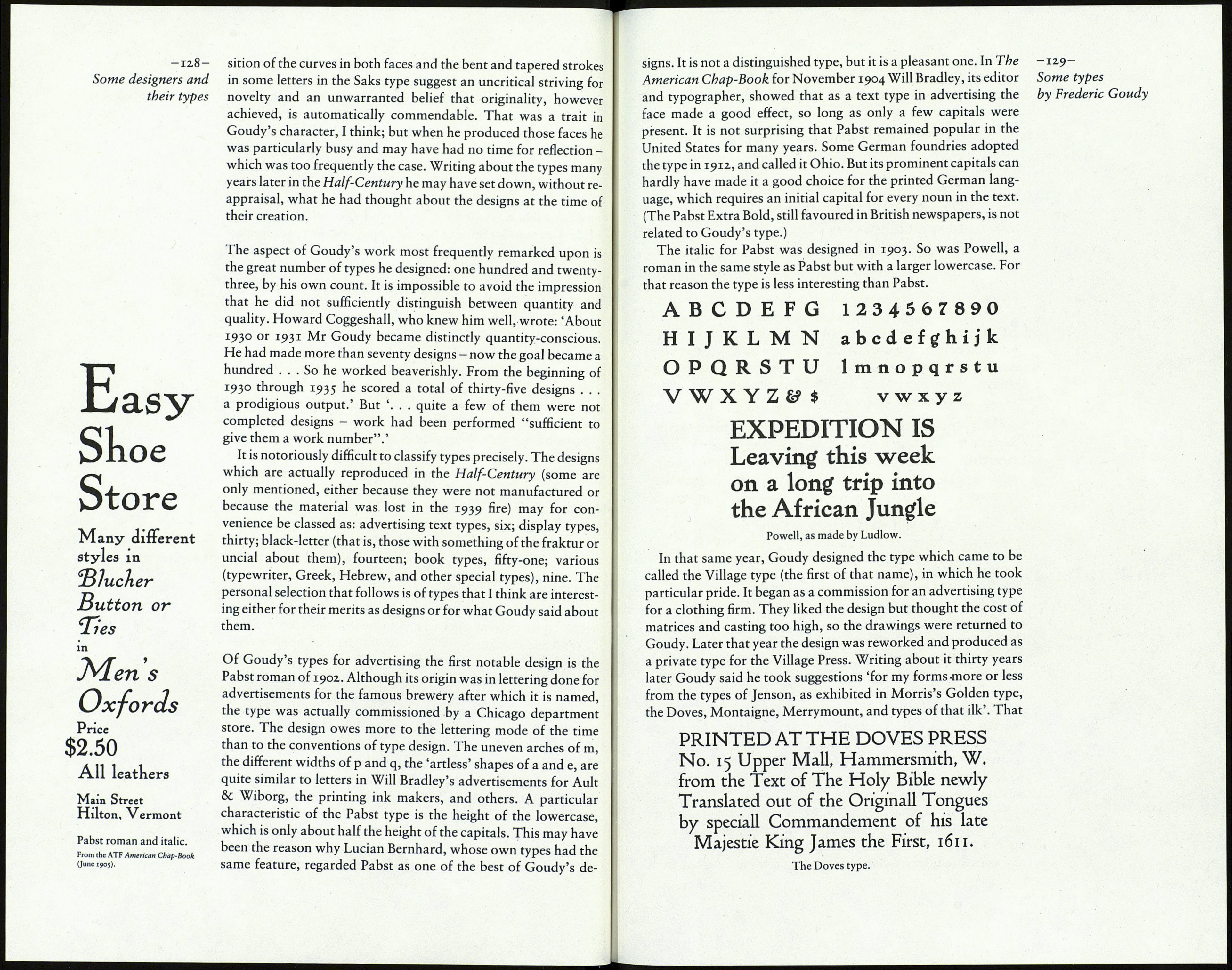

Like other creative people designers are seldom good critics of

their own work. Certainly some of Goudy's opinions of his de¬

signs are difficult to accept. For instance, about the Companion

Old Style face intended for headings in the Woman's Home

Companion magazine he wrote: 'I believe it is one of the most

distinctive types I have ever made. It incorporates features which

deliberately violate tradition as to stress of curves, but which are

so handled that attention is not specifically drawn to the innov¬

ations introduced.' And of the Saks Goudy design: 'I believe it is

as good a type as I have ever made, or can make . . .'But the plain

fact is that those designs are distinctly clumsy; the curious dispo-