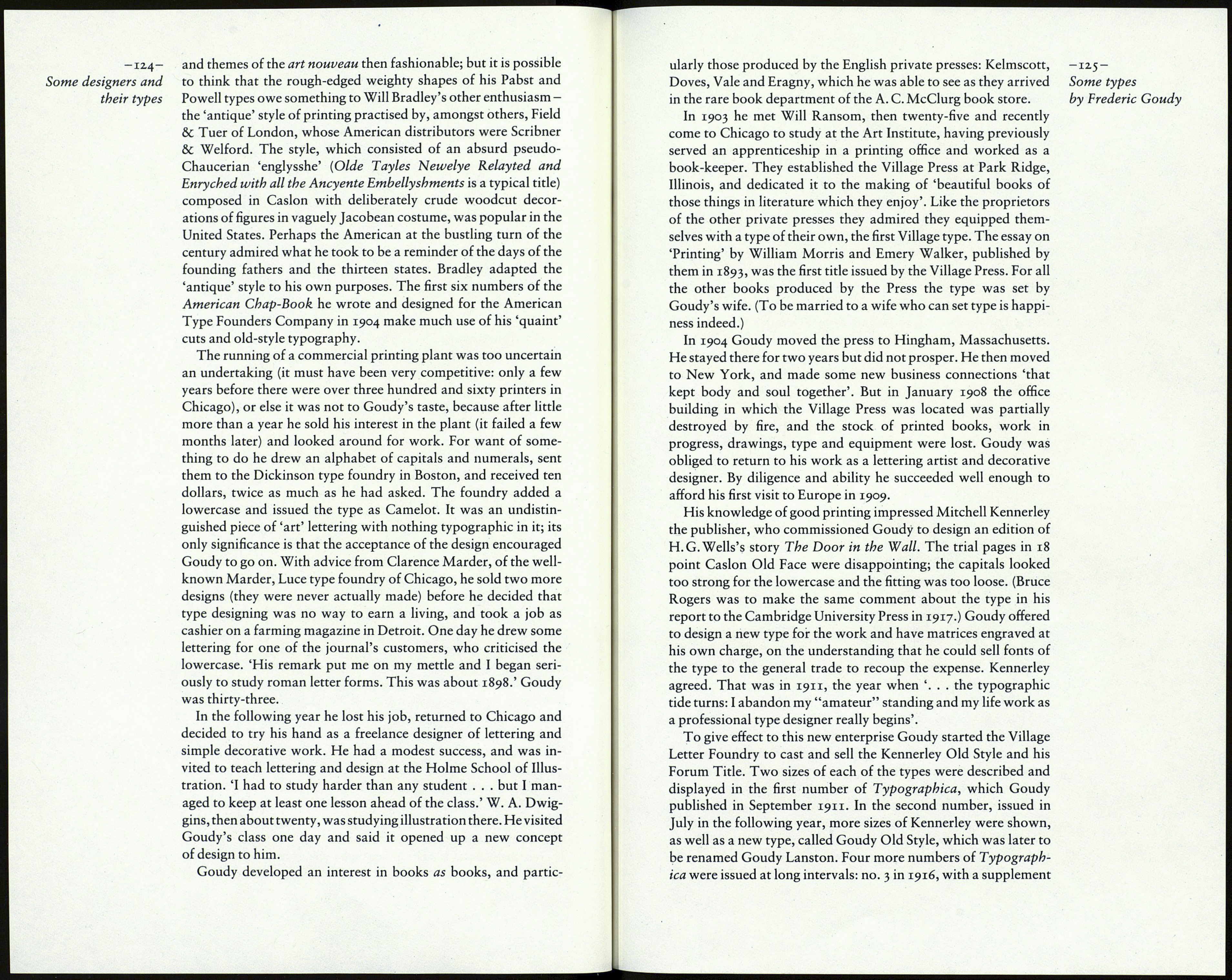

-122- ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOP

Some designers and _, _

their types Q.RSTUVWXYZ &.,*;:!?-

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ&

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuv

wxyzfiffffiflffl£]] 1234567 890

ABCDEFGHlJKLMHOPSiRS

TUVWXYZ& alcdefghijklm

nof^rstuvwxyzjifffjijlfflä .,';:/?-

And now to the subject which has been assigned to me for this

occasion—something about types of the past, type revivals, and a

bit about type design, as I see it. I trust you will not find that my

brief postprandial attempt bears out Gay's lines too literally:

So comes the reckoning when the banquet's o'er,

A dreadful reckoning, when men smile no more.

ONE hundred and twelve years ago type design was generally im¬

agined to be a matter that concerned only the letter cutter. J. John¬

son, author of Typographia (published in 1824), wrote of a type face

that the printer needed only to "observe that its shape be perfectly

Deepdene roman and italic.

that appeals to me drawn by another hand, I try to secure in my

own drawings some certain movement or rhythm his may pre¬

sent. I soon discard my model and proceed from there, as it were,

under my own steam . . .'

The statement is interesting, because much has been said in

recent years of the sanctity of the type designer's creations and

the iniquity of plagiarism. Condemnation is certainly justified

when a manufacturer flagrantly reproduces another's design

without permission while the design is still within the period

when copyright applies, or should apply, to that class of in¬

dustrial design. But it is unrealistic to disapprove of a designer

who takes note of a feature or characteristic in another type and

uses it as an element in a new design of his own. (Composers of

music have frequently 'quoted' each other without criticism;

indeed, Ravel said, 'It is by imitating that I innovate.'). Only if the

borrowed feature has a dominant part in the character of the type

may a charge of plagiarism be levelled at the designer.

Certainly that is not the case with Goudy. Whatever he bor¬

rowed from others was always thoroughly subsumed as soon as

his own inventive powers, stimulated into action by the source of

interest, took command of the work. The outcome was invari- -123-

ably and unmistakably a Goudy design. Some types

by Frederic Goudy

In his own time Goudy was a hero figure in American printing:

'Glorifier of the Alphabet' was how a New Yorker profile des¬

cribed him in 1933. Though his reputation is no longer every¬

where as high as it was, there are still many people in the United

States who regard his achievements with warm-hearted, if uncrit¬

ical, reverence. His life and work have been extensively recorded

in his own lectures and writings and in the reminiscences of

others. There can be few students of typography in the United

States who are unfamiliar with the details of his career. On the

other side of the ocean the case is different. The following short

account of the main events of his professional life will, it is hoped,

provide sufficient background to the appraisal of his type designs

which is the chief purpose of this essay.

Goudy had a long life. He was born in 1865 in Illinois and died

in 1947, in his eighty-second year. As a boy he had a keen interest

in lettering, and when his father took up the real estate business in

1884 (he had been a schools' superintendent) Goudy worked for

him and frequently designed the office advertisements, with

hand-lettered headings to give them distinction.

For several years he worked as a cashier or clerk in various

cities until he settled for a time in Chicago. In 1895 a chance

meeting with a friend who offered to provide some cash enabled

Goudy to start a small printing office, which he called the Booklet

Press. He acquired the equipment - a Golding press, an imposi¬

tion stone, a few cases of Caslon and an 'English' text - from Will

Bradley, who had bought it for pleasure printing but was too

busy to use it. No doubt Goudy added to this modest equipment,

because the first substantial commercial job undertaken by the

Press, soon renamed the Camelot Press, was the typesetting of the

second year's issues of The Chap-Book, the influential literary

journal published fortnightly by Stone &c Kimball (the actual

printing was done elsewhere). Bradley designed some covers and

posters for it in skilful imitation of the style of Aubrey Beardsley.

In Goudy's words: 'I began my work in that period of transition

known as le fin de siècle; I belong to the Beardsley period, al¬

though actually never a part of it.'

Goudy was lucky to be in Chicago during the 1890s. Stone &C

Kimball and others made a significant mark on the American

publishing scene, which attracted the interest of literary people in

London and Paris. The high quality, literary and graphic, of the

Chap-Book 'opened my eyes to a new world', said Goudy. He

became aware that typography, properly executed, was itself a

craft, and a source of visual satisfaction.

Whether he was much influenced by what he saw is difficult to

say. There is no sign in his early work of any interest in the style