-92-

Aspects

of type design

WEIN

KARTE

Jakob Erbar's Feder-Grotesk.

the use of precise grids, the limitation of decoration to the 'pure'

elements of geometry, the line, the square and the circle, and

sans-serif as the type best suited to express the ideals of the mod¬

ern creed. There were many sans-serif types to choose from; the

1926 volume of the Handbuch der Schriftarten shows well over

three hundred of them in current manufacture. But most of them

were dull and lifeless, inadequate to express the spirit of the age.

The form must be re-created. The type founders recognised a

promising field for enterprise, and the type designers responded

to the challenge. The fundamental elements of geometry, the

straight line, the circle and the arc, would provide the basis for

the new types which, purified of any traces of the past, would

speak for the aspirations of 'our time'.

Three of the new German sans-serif faces became internation¬

ally famous: Jakob Erbar's eponymous design, Paul Renner's

Futura, and Rudolf Koch's Kabel (which will be discussed at

length in later pages). All three of them are frequently in use at the

present time.

The Erbar face was first in the field. Jakob Erbar had already

designed a serifless type in 1919, though it was not a sans-serif in

the full sense. Its main and secondary strokes were visibly differ¬

ent in thickness, because the type was meant to reflect the action

of a broad pen - hence its name, Feder (quill) Schrift. (Erbar knew

something of calligraphy; he had attended the class conducted by

Anna Simons, one of Johnston's pupils.) The Feder type was

undistinguished; Erbar's later Koloss, a heavier face on the same

lines, was a much better design. There is no obvious connection

between those faces and the sans-serif design that later made his

name internationally known. He wrote that he did the first rough

ÄBCDCEFGHIJKLMNQ

PRSTÜVWXYZ

abcdefghijklmnöpqrst

Erbar:

the 1922 drawing.

uvwxyz

1234567890 i)

drawings for a modern sans-serif type as early as 1914, but his

service in the First World War interrupted the work. A set of

capitals was drawn in 1920, and another drawing of 1922 shows a

complete font, on which the letter forms are not greatly different

from the type as it appeared in 1926. 'My aim,' he wrote, 'was to

design a printing type which would be free of all individual char¬

acteristics, possess thoroughly legible letter forms, and be a pure¬

ly typographic creation.' He went on to say that it was clear to

him that the task would only be accomplished if the type face was

developed from a fundamental element, the circle. The letters с

and e, and the bowls of lowercase b, d, g, p and q all relate to the

circular o, which was fairly small compared with the capital O. In

the supplement to the Handbuch for 1927 the new type is shown

in full alphabets in light, medium and heavy weights, the light

and medium having an alternative lowercase of reduced x-height,

which was not exported. The type was introduced in 1926,

-93-

The sans-serif

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO ABCDEFGHIJKLMN

PQRSTUVWXYZ abcde OPQRSTUVWXYZ

fghchijkcklmnopqrsifjtu abcdefghchijUclmnopqrsfljrh.

vwxyzäöü 1234567890 uvwxyz äöü 1234567890

Erbar: the normal and small x-height versions.

From the Handbuch der Schriftarten.

though the related inlined bold version, called Grotesk Lichte

Fette but known as Phosphor in Britain and America, had already

been available for three years, if the date given is to be believed. In

the same supplement three weights of the Futura face were shown

in one-word samples.

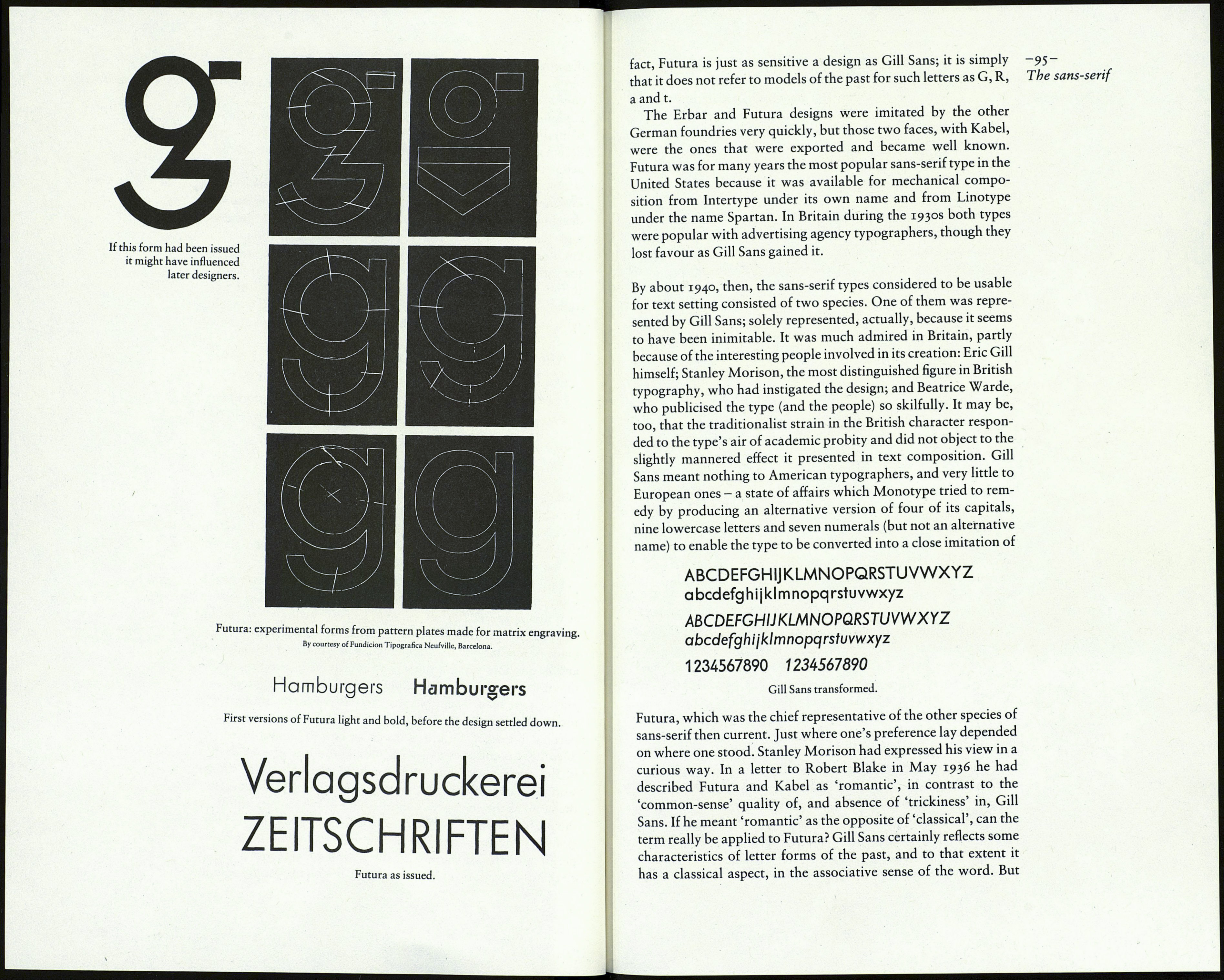

Paul Renner evidently found the creation of a sans-serif on a

geometric basis a stimulating task. In the light version of Futura

as it first appeared his lowercase m had a flat roof (there was an

existing Grotesk called Roland that had the same feature). The r,

made of a pillar and a separate ball, is a typical art deco device;

and in the bold version the a is an ingenious play on the tradi¬

tional shape. The g, a lively exploitation of geometric forms, was

one of two such inventions, as the pattern plates shown here

reveal. (I prefer the other.) The pattern plates are interesting for a

particular reason. Futura is taken to be representative of the

'Germanic compasses-and-set-square school', as one writer has

it. But these plates show four versions of the familiar single-

storey g. They differ by the amount of modelling in the curves of

the bowl as they enter the stem - a sign of refined perception in

the person responsible. That is not all. The three cancelled ver¬

sions have a 'compassed' counter in the upper section; but in the

permitted version, the one finally adopted, the counter is not

circular but oval, as in the p and q - and it is all the better for it. In

The early versions

of these characters

are shown overleaf.