-8o- letterspacing was understood and practised by most typo-

Aspects graphers and many typesetters, and headlines in capitals worked

of type design well and looked well. Now the art is in abeyance-except where a

serious typographer makes the effort to refit the output by hand.

LAWYERS

Rub-down kerning out of control.

From an advertisement in an English newspaper.

If the kerning of capitals with capitals was deleted from

'refinement' programs the capitals would at least present them¬

selves naturally; sometimes awkwardly, no doubt, but not ridicu¬

lously, as is too often the case.

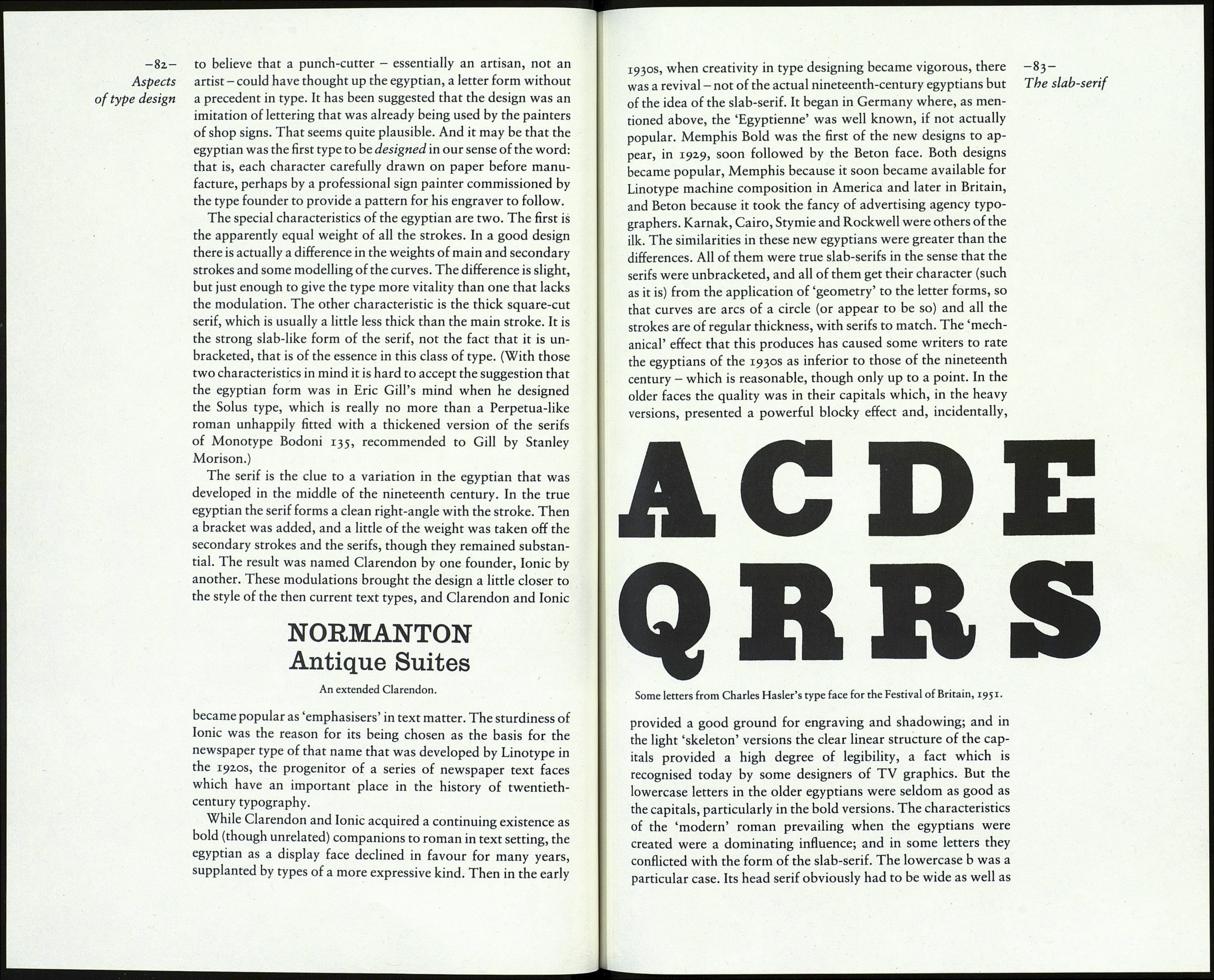

II: The slab-serif

There are two classes of type faces which, though they are not

used in book printing, frequently perform as text types and there¬

fore deserve some examination. They are the egyptian and the

sans-serif; occasionally used for the text of magazines and for

features in newspapers (chiefly in the European press), but more

often for the 'copy' in sales catalogues, promotion material and

press advertising.

It was advertising that brought them into being in the early

years of the nineteenth century, when the promoters of lotteries

and entertainments and coaching services wanted their placards

to shout to the passer-by with a louder voice than had been

delivered by the display sizes of the Caslon and Baskerville style

types previously in use. The egyptian and the sans-serif, with the

fat face which came first in order of invention, were the three

radical innovations in type design which removed the typo¬

graphy of ephemeral printing from the influence of the book and

enabled it to acquire a visual style of its own. At first the fat face

was the most potent. Its basis was the 'modern' face, with its

characteristics carried to the extreme - its thick strokes made as

broad as possible while the thin strokes and serifs remained hair¬

like. Fat face types, in roman and italic, were staples in display

typography until the last quarter of the nineteenth century. As a

species the fat face was revived in the 1930s, and it has continued

in mild favour; Poster Bodoni and Ultra Bodoni are well known,

though Falstaff is a better design than either. The fat face is the

ultimate of a class, not a class in itself; and because it is not usable

in continuous text it is outside our area of study.

Vincent Figgins was the first type founder to show the egyptian

or 'slab-serif, in a supplement (c. 1817) to his specimen of 1815, -81-

where it was called 'Antique'. The design consisted of capitals The slab-serif

only; no doubt there were numerals too. The characters were full

HISTORIANS have informed us it

happened that about the year 1706

An 'Antique' from a Figgins specimen book of about 1887.

face titling in four sizes, approximating 12, 22, 48 and 60 point,

and were presumably intended to be used in a subsidiary role to

the fat face types, which Figgins offered in a range of sizes up to a

stentorian 192 point. (It may be, though, that independent wood

letter makers were already producing the 'Antique' letter in sizes

larger than Figgins's.)

Not everyone admired the new design. In his Typographia

(1825) Т. С Hansard was scornful. 'Fashion and Fancy com¬

monly frolic from one extreme to another. To the razor-edged

fine lines and ceriphs of type just observed upon [the fat face],

a reverse has succeeded, called "Antique" or "Egyptian", the

property of which is, that the strokes which form the letters are

all of one uniform thickness! - After this, who would have

thought that further extravagance could have been conceived?'

(He went on to fulminate about the 'Italian' face, the 'reconstruc¬

ted' fat face mentioned earlier in these pages.) And in 1834 the

Journal für Buchdruckerkunst of Brunswick showed that it was

paying close attention to Hansard by describing the new type as a

'Monstrosität' - which now seems altogether too severe for what

we regard as a plain serviceable letter.

About the name: at the time of its creation there was great

public interest in Britain in the relics of antiquity, especially in the

accounts of what was seen during Napoleon's expedition in

Egypt. The 'antique' was fashionable, and type founders prob¬

ably saw commercial advantage in naming their new designs

according to the vogue. Robert Thorne was the first to use the

term 'Egyptian', and in the course of time that came to be the

accepted term for the slab-serif class. The 1926 volume of the

Handbuch der Schriftarten - the volume that encapsulated the

range of types available in Germany before the great surge of new

designing in the 1930s - shows forty-five types called 'Egypt¬

ienne', in various weights and widths. In its English and French

forms the name is present in modern digital type face catalogues.

As said earlier, the fat face, extraordinary as it looks by com¬

parison with traditional book types, was really the idea of the

bold version of an established text type, the 'modern', carried to

the extreme. It is not difficult to imagine a punch-cutter respond¬

ing to a demand and cutting an exaggerated version of a style

with which he was familiar. On the other hand, it is very difficult