-6z- distinctly different values. His article 'Towards an Ideal Italic', in

Aspects the fifth volume of The Fleuron (1926), is one of the most remark -

oftype design able of his writings. The first half is a valuable account of the

history of the italic form, in which he records and illustrates the

change from the calligraphic appearance of the early types, with

their wealth of tied letters, to the disciplined italics of the eight¬

eenth century. He mentions the italic of Grandjean's romain du

roi, which A.F.Johnson said was the first example of a true sec¬

ondary italic, designed for, and at the same time as, a specific

roman. Morison speaks of an italic cut for F. A. Didot as being

'the best example there has been of a regular formal italic' but

remarks that 'it is to be regretted that all trace of calligraphic

originals has not been removed'. He then moves to the chief

purpose of the article: to advance the proposition that the in¬

formality of italic as we know it is incompatible with the calm

regularity of roman; that its single useful characteristic is its

slope, which is all that is needed to provide differentiation; and

that therefore the truest type to serve in the secondary role is a

sloped version of the roman. He argued the case with his custom¬

ary vigour. 'Certainly a type of conspicuously different colour

and design from that of the roman cannot be tolerated, for it is

clear that maximum repose will attach to a page where the roman

and italic most nearly approximate.' He illustrated his proposal

with a selection of characters from the Caslon face, in their

roman form and also specially drawn to an angle of 15 degrees.

What he did not do was to comment on any of the sloped roman

types already in existence. For example, he could have referred to

the catalogue of 'self-spacing' types issued by the Benton, Waldo

GLOBE JOB ROOMS-SAINT PAUL.

In January, 1886, I put in a font of Self Spacing and I am

glad to state to you that from the total amount of composition

of four compositors for sixty days, I estimate that the saving by

increased composition was equal to the whole cost of the type.

The Benton-Waldo sloped roman.

type foundry of Milwaukee about 1886. All the 'italic' faces in it

are actually sloped romans*; one of them was shown in the first

volume of T.L. De Vinne's Practice of Typography, a work

which Morison admired. And closer at hand, frequently to be

seen in the printing of the 1920s, was the De Vinne type (the one

* In an article in The Inland Printer of October 1922 H. L. Bullen called them an

'innovation'; but there were others in existence, usually display types. The

Milwaukee foundry probably made them by necessity, the urgent need to get

their self-spacing types on to the market, and that may have been the reason

why Benton invented his 'Delineator' machine, which enabled him to use one

set of roman drawings to produce, very rapidly, variations of the design, includ¬

ing slanted versions, for the making of the patterns for electrotype matrices.

created by the Central Type Foundry, not the American Linotype -63 -

text face). In my early days in a London composing room it Secondary types:

ranked in popularity with Cheltenham Bold. It could not have italic, bold face

escaped Morison's attention. Its italic was a sloped roman, with

no concession to calligraphic influence. If Morison had paused

and glanced at it, and at the Milwaukee faces, he might have

hesitated to press his sloped roman theory in so uncompromising

Spanish**American War

Parfumerie Hygiénique

Gustav Schroeder's De Vinne 'italic', 18 point.

a way. It is a little confusing to find, in A Review of Recent

Typography (a revised edition of an earlier work) published the

year after the 'Ideal Italic' article, Morison describing the

Tiemann Kursiv face as a 'handsome letter, flowing as an italic

should be . . .' (my italic). Presumably the passage had not been

revised as thoroughly as the rest of the book. In the last volume of

The Fleuron, issued in 1930, he wrote approvingly of a new suite

of types by Lucian Bernhard who, said Morison, 'is the first type

designer to put into practice the principles laid down in suc¬

cessive articles in The Fleuron as to the relation of roman, sloped

roman and script — the trinity in which, it was forecast, con¬

temporary type faces must henceforth appear'. Bernhard's types

were hardly the best sort of support for the dogma Morison was

asserting, being 'fancy' types only suitable for advertising work.

Morison had tried to put the sloped roman idea into effect in

the italic of the Perpetua type, a new arrival which provided an

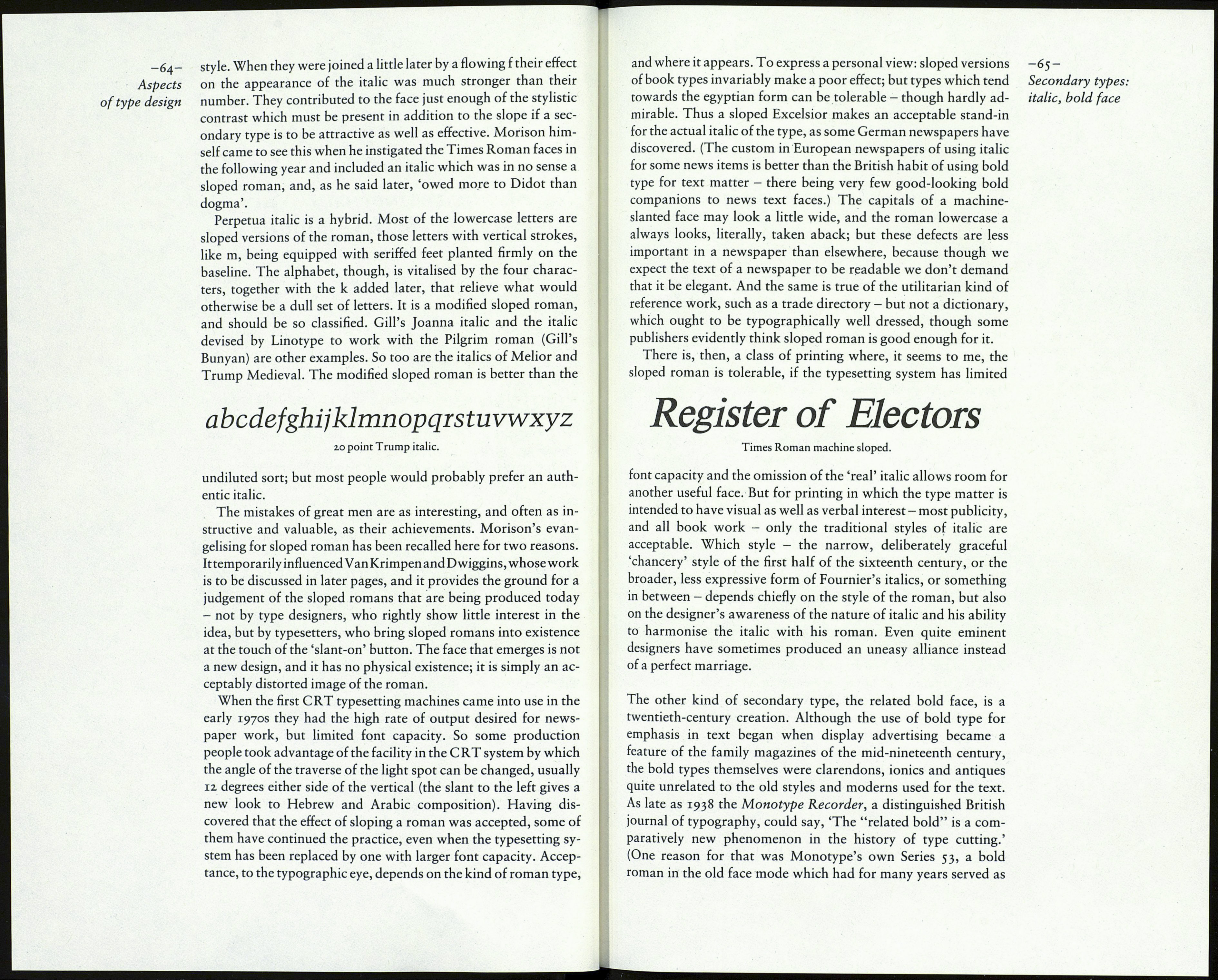

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

30 point Perpetua italic.

important item in the same volume of The Fleuron. The type was

described by Beatrice Warde in an article on the typographic

work of Eric Gill. With more loyalty than accuracy she wrote:

'Perpetua italic . . . interestingly carries out the prediction first

made in the fifth number of The Fleuron that, if the italic is to

develop into a contemporary form, consistency demands that it

should no longer retain the calligraphic peculiarities derived

from a school of writing quite different from that of the roman;

that it must, in fact, become frankly the italic of the given roman,

with only slope, and the modifications necessary to slope, to

distinguish it from the upright version'. But the specimen that

accompanied the article shows that Perpetua italic was not the

uncompromising sloped roman of Morison's 'ideal'. It contained

three significant characters, a, e and g, which were not simply

inclined versions of the roman but calligraphic and 'informal' in