-6o- form and detail may be the chief element of its novelty. But

Aspects designers of text types have to obey the rules; not only because

of type design the aesthetic quality of each letter depends on that discipline, but

because, to quote Updike, 'a test of the excellence of any type is

this - that whatever the combination of letters, no individual

character stands out from the rest - a severe requirement to

which all permanently successful types conform'. How, then, do

designers contrive to create new types that preserve the natural

features of letters and yet are visibly different from others of their

kind?

They may take advantage of the simple variations of struc¬

ture already mentioned - the splayed or vertical legs of M, the

treatment of the foot of b, and so on - but those modest choices

are not themselves sufficient to produce the degree of originality

that is the designer's objective. Distinctive identity comes from

the characteristics that are additional to the structural ones; the

flesh on the skeleton, so to speak. The most important is the

relative thickness of the strokes that form the letters. If the 'thick'

stroke (the second stroke of A, say) is actually not very thick, and

the 'thin' stroke is fairly robust, and that is the case with all the

letters in the face, then the texture of the type will be quite even,

and perhaps monotonous, in the literal sense of the word. But if

the stroke weights are organised the other way, the main strokes

strong, the secondary ones fine-drawn, the contrast between

them will be evident and the effect of the type on the page will be

incisive and possibly dazzling - though not necessarily more

agreeable to the eye. The amount of contrast produces the parti¬

cular texture of a type, and it is the first aspect of a type face that

the student takes note of in the process of identifying it. If the

contrast is not particularly marked the type is not Bodoni and

probably not one of the many other modern faces. If, though,

there is enough contrast to make a moderately clear-cut effect the

type is unlikely to be Pilgrim (Eric Gill's Bunyan), which is a very

even-textured type; and it may not be Baskerville, which in some

printing makes a fairly bland effect. Stroke weight and contrast,

then, help to establish the general class of a type face.

The next feature to note is the stress or bias in the round letters,

о, с and e, and those with round parts, b, d, p and q. If the

maximum weight is at three or nine o'clock the stress is said to be

vertical. It is a characteristic of the transitional types and the

moderns. If the weight is at two or eight o'clock the stress is

oblique, and that is characteristic of old style faces.

The other feature to which the designer of a text type gives a

good deal of thought is the serif. The length of it is not really at his

choice, because it is determined by the spacing, the 'fitting', of the

characters - a subject to be dealt with a little further on. The

shape of the serif is a matter of choice, and the range of possibility

A medley of serif shapes, is considerable. It can be thick or thin. Its end can be sharply cut

or rounded off. It can be bracketed to the stroke, or unbracketed. -61 -

It can even be wedge-shaped. Secondary types:

Stroke weight and contrast, stress and serif shape are three of italic, bold face

the means by which the designer, combining and permuting

them, achieves the particular individuality of a new type face.

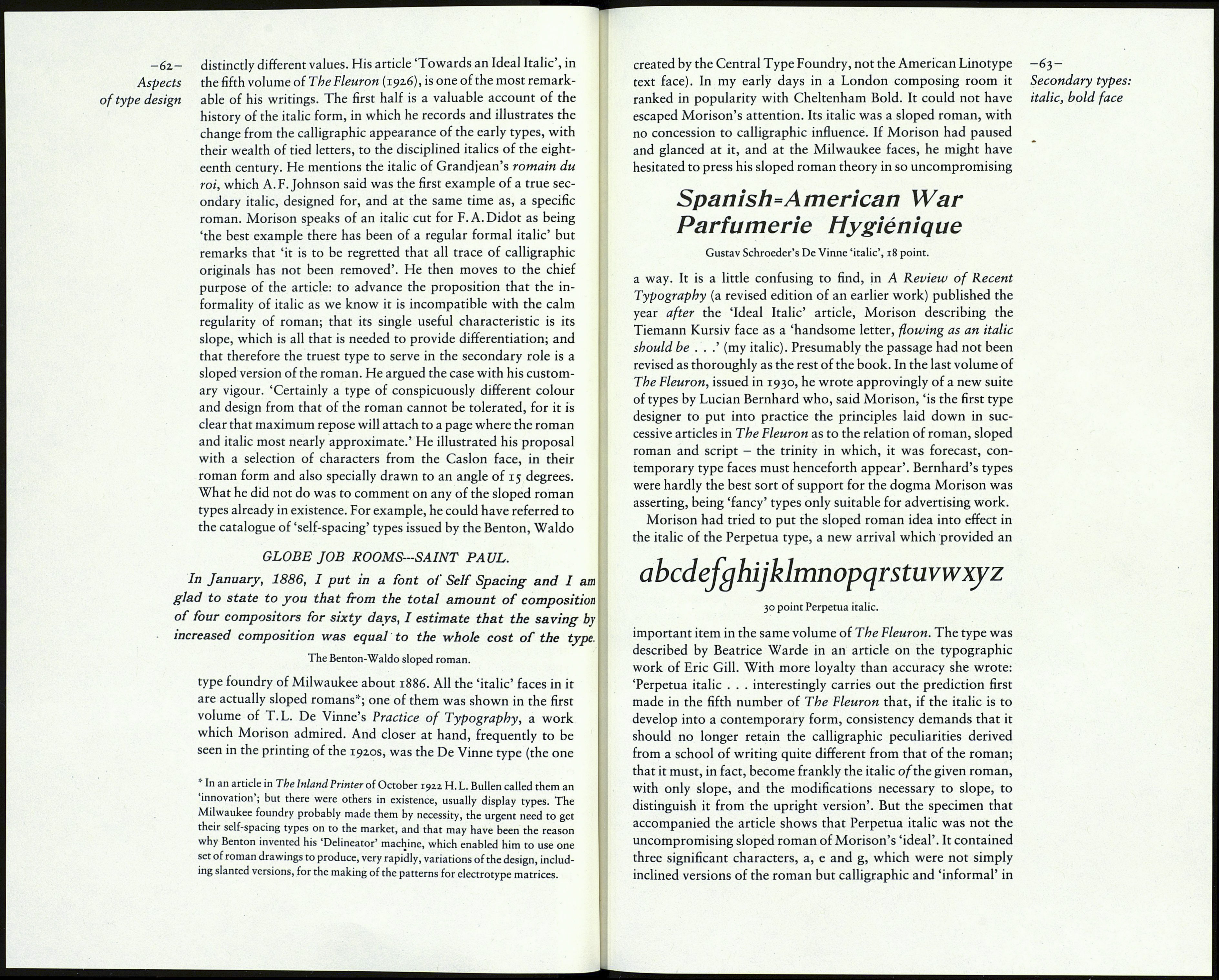

8: Secondary types: italic, bold face

A. F. Johnson described italic as 'a sub-division of roman',

because it derived from a similar source, one of the styles of

writing practised by professional scribes in Rome at the end of

the fifteenth century; this particular style being gracefully narrow

in form and therefore well-suited to the printer's desire to contain

a long classical text within a smallish book. Some of the early

italic types were upright, though informal in character. So 'italic'

refers to place of origin and, more particularly, style; it does not

really mean 'inclined', though that is usually implied when we

use the term nowadays. For the first quarter of the sixteenth

century only the lowercase was italic; the capitals were roman.

And it was not until the middle ofthat century that italic began to

be used as an auxiliary to roman, for words in a foreign language,

for emphasis, for the titles of other works, and so on. 'Secondary'

was Stanley Morison's convenient term for that aspect of the

function of italic. An italic font, then, can perform two roles: as a

text type - in which case the secondary type, for the title of a

quoted journal, say, is the roman; and as an auxiliary in a roman

text.

In Germany, well into this century, italic was not regarded as

essential. It was allowed that differentiation could be indicated

by using roman but letter-spacing the particular words, a custom

familiar to German readers from their experience of fraktur

types, in which an inclined form was not a possibility. Ellic Howe

records that the London Family Herald of 1822 did the same

thing, but for a different reason: its text was composed on a

machine that had no room for a second type. George Bernard

Shaw, who had ideas about typography, specified letter-spaced

roman lowercase for the emphasis in speeches in the early printed

edition of his plays.

The distinguishing features of the traditional italic characters

are, first, a general effect that they run together (which is why

cursive is a more appropriate name for the style), and second, the

slope of the letters, which may be as various as the 25 degrees of

Caslon's italic and the near-upright 4 degrees of Eric Gill's

Joanna italic. Stanley Morison saw those two factors as having