-58-

Aspects

of type design

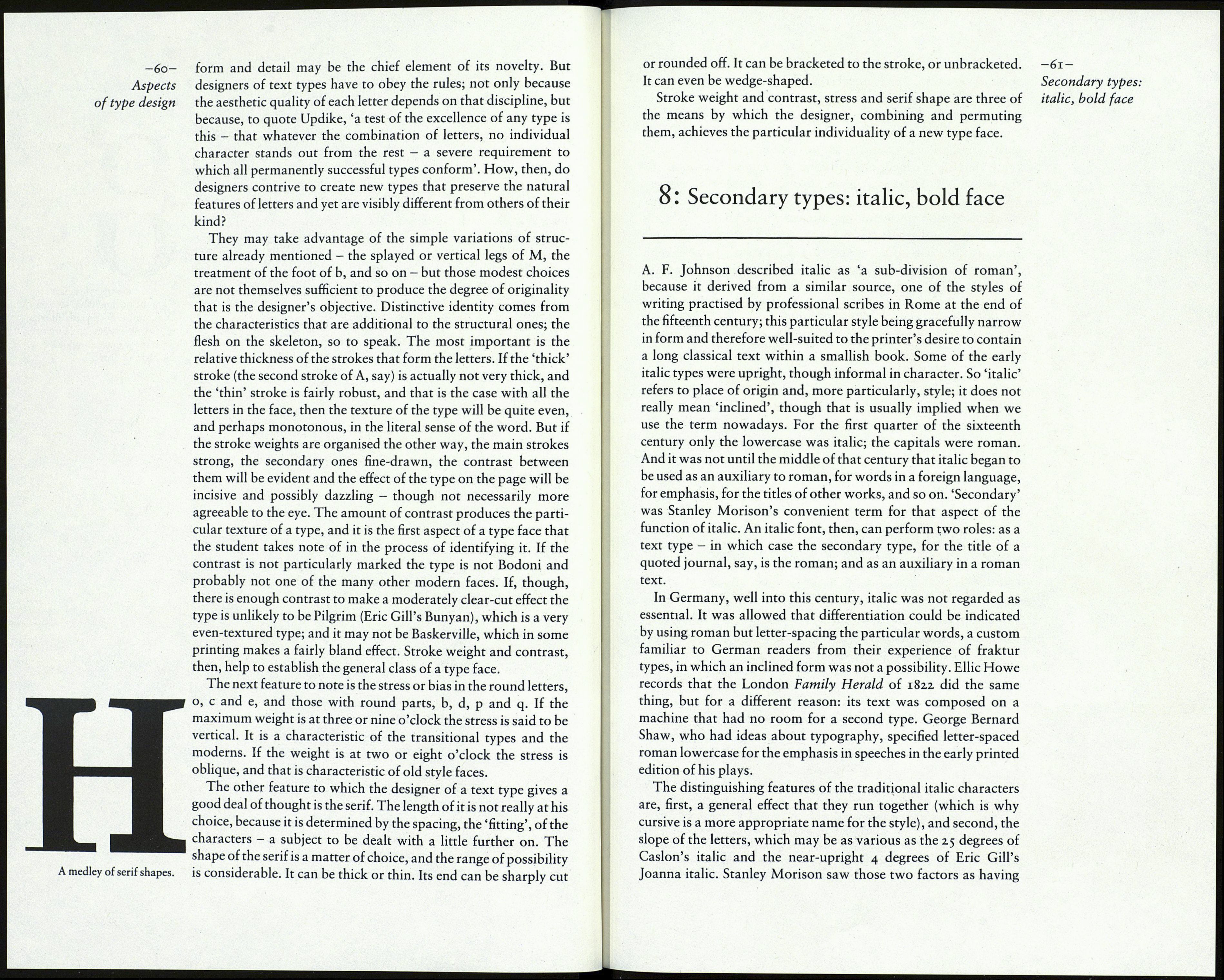

МЫ)

Lowercase letters derive from

calligraphic sources. When they

are carefully written it is

natural, not a mere convention,

for the stem to carry a serif on

the left. The d in this hand-

drawn feature title in a London

newspaper breaks the rule, to no

good effect.

the two-storeyed form becomes the least happy letter on those

occasions when a roman face in a CRT typesetting system is

slanted to simulate italic.

The significant part of the letter b is the lower end of the stem.

In some old style types it terminates where the curve of the bowl

flows into it. In others it ends in a short tapered element.

Compare Bembo and Caslon. The 'rational' type cut by Phillipe

Grandjean in 1693-1702 for the royal printing office in Paris

introduced a new feature: a serif at the foot of the stem, as though

the letter was simply a reversal of the letter d. The style was

adopted by many of the later punch-cutters who produced 'mod¬

ern' faces. It is in Bulmer, but not in Scotch Roman; in Bodoni,

but not in Walbaum.

The design of the lowercase e in text faces produces strong

feelings (or should do so). The slanting bar was a feature of the e

in Nicolas Jenson's and other roman types before 1500. Then it

was discarded in favour of the horizontal bar. It reappeared in the

'Basle' roman of 1854 used by Whittingham, and then in William

Morris's Golden type and other private press types derived from

the Jenson roman, including Bruce Rogers's Montaigne face of

1901. It was when Rogers's Centaur type of 1915 was adopted by

Monotype in 1929 that the general typographer became aware of

the letter. In that type, the most elegant version of the Jenson

face, the slanting bar is perfectly acceptable. But to my eye the

form sometimes has an unwanted restlessness. Goudy was over-

fond of it; and some recent designers seem to have seen it as an

easy option, a facile way of adding instant 'character' to a type

face.

What was said about the lowercase a applies almost equally to

the letter g: two forms, a two-storey one and a single-storey form

with a tail; both of ancient origin, the single-storey g being the

form present in the early German textura types used by Guten¬

berg, the other form occurring in the less formal type used by

Schoeffer at the same period. It was the two-storey form that

became the standard in roman text faces. By contrast, and show¬

ing their relationship with fraktur types, almost all the 'Neudeut¬

sche Schriften' in the Handbuch der Schriftarten have the single-

storey form of g. The same is true of the 'Grotesk' (sans-serif)

types which were current in Germany in the first twenty years of

this century. The case was quite otherwise in American and Brit¬

ish sans-serifs, where the single-storey g was unknown - though

familiar enough in traditional italic types. The single-storey form

is therefore German in origin, though now universally accepted

in sans-serif faces, including some not by German designers. It is

(rightly) seldom seen in seriffed faces, other than egyptians; the

classified advertisement type called Maximus, used at 4! point, is

an exception.

The letter h in some italic faces is a matter for concern. Two

kinds are current. The one whose lower half resembles the letter n

- that is, its second leg is straight, with a short upward terminal to

the right - first appeared in the italic of Grandjean's romain du

roi of 1702.. It was imitated by Fournier and then by Firmin Didot,

and it became the standard form of the letter in 'modern' faces.

Caslon did not adopt it, but Baskerville did. The other kind of

italic h is the one that was present in all the italics from the first

Aldine type up to Kis's 'Janson' and Caslon's italic. It has the

right leg bent into the interior of the letter, which makes the h

look very like the letter b in small sizes. Worried about this, some

designers have kept the base of the letter fairly open, with the

result that the right leg looks feeble. The h in the Sabon italic is an

example; it is the only disappointing letter in this admirable type.

Small things matter in type designing: the dot of i and j, for

instance. In a sans-serif type it is naturally centred over the width

of the stem. But in a seriffed face it is optically more satisfactory

when it is placed a little to the right of centre. In early faces the

dot was quite small. Where that characteristic has been cont¬

inued into the revived version of an early type, as in Centaur and

Bembo, or respectfully imitated, as in Lutetia, the dot becomes

vulnerable to the short light-flash in photo-composition and in

offset-litho platemaking, and sometimes disappears in print.

If it is to remain fully identifiable the lowercase 1 cannot afford

to give away any of itself above the level of the top of x. In faces of

large x-height that part is, in effect, diminished, and the letter

loses more of its identity than any other ascender character.

In old style types the bowl of roman p has a tendency to 'pull'

the letter out of true, so the stem was often given a degree of angle

to counteract the effect - a refinement that is discouraged when a

type is to be digitised, for fear of a saw edge to the stem. An

increase in the length of the right-hand foot serif helps to keep the

letter in balance.

The letter t in old style romans has a bracket to the left side of

its cross bar. In 'modern' romans the bracket is usually, but not

always, omitted. In italic faces the distinction is not so clear-cut.

In the Biado italic for Poliphilus and in the Bembo italic the t has

the bracket; in the italic for Centaur there is no bracket.

Lowercase y frustrates the designer, who wishes the ball at the

foot of the letter could be allowed to kern below the preceding

letter - until he or she remembers that the preceding letter is

frequently g.

-59-

The forms of letters

One of the unusual variations

from the normal which Pierre

Didot introduced in his effort

to make his types look different

from those made famous by

his brother Firmin.

Those are some of the natural features of type faces old and new.

'Natural' is the right word, because they are more than mere

conventions. They may be ignored or deliberately flouted by the

designers of publicity types, as a painter may discard the rules of

perspective - reasonably enough, because a publicity type is re¬

quired to be different from the traditional, and eccentricity of