-54- degrees from the vertical. This means that 6 point in color and

Aspects width is approximately 71 per cent of 12 point, and not 50 per

of type design cent. And the eye is the sole arbiter of proportion after all . . .'

When photo-composition became a reality in the 1950s the

manufacturers of typesetting machines had to make an import¬

ant decision: whether or not to carry forward into the new system

the principle of optical compensation, when the plain and tempt¬

ing fact was that the photographic part of the system was capable

of producing a considerable range of type sizes from just one

font. To abandon the principle altogether was to risk forfeiting a

substantial part of a reputation for typographic quality. The

manufacturers faced the problem by compromise. American

Linotype produced film replicas of both the 8 and 12 point ver¬

sions of text types, and of the 18 point where display sizes existed.

To judge the effect of using 8 and 12 point as masters to produce

other sizes the Falcon type, previously mentioned, can be used as

an illustration. Ten point from the 8 point would have been

about 10 per cent wider than the metal version; 10 point from the

12 point would have been about 7 per cent narrower than the

metal. In fact, by comparison with the optical proportions de¬

scribed by Griffith, all sizes except the 8 and 12 point would have

varied from the ideal - the sizes which were reductions from the

artwork being weaker than the metal versions, and the sizes

which were enlargements from it being clumsier. This compro¬

mise between the full scope of former manufacturing finesse and

the geometrical progression inevitable in electronic typesetting

can only be regarded as a loss of some of the refinement of types

as they used to be. It was probably the only course possible at the

time.

Ultimately, though, it was for the printer to decide whether he

would buy more than one font of a type face to satisfy the typo¬

graphic sensitivity of his customers. Unfortunately, it became

clear that some printers preferred to sacrifice typographic quality

for economy in capital expenditure. This encouraged some

manufacturers, especially those who had entered the field with¬

out a 'bank deposit' of existing letter drawings, to think that if

printers were willing to use a single font for all sizes of type then

there was no need to bother with optical compensation. Some of

them apparently thought that increasing the x-height of the faces

would be an acceptable alternative. It is not. Although it assists

the legibility of small sizes it vulgarises the larger ones.

To make a choice from a broad range of working drawings of

just one size of artwork for a master font that will be used to

compose a band of type sizes is an anxious business. Too much

concern for the look of the display sizes may mean that the art¬

work size chosen, say the 12 point, produces a cramped result at 6

and 8 point. Nervousness about the small sizes may result in a

abcdefghijklmnopqrstu zichzelfte behoeden

vwxyzij wijt van eentonighe

Geen enkele drukker mag, om zichzelf te b Geen enkele drukker mag, om zichz<

van eentonigheid in zijn zetwerk, tegen bel verwijt van eentonigheid in zijn zetw

in het veronderstelde belang van versiering, gedogen dat, in het veronderstelde b

logica en duidelijkheid door enige typografis weld gedaan wordt aan logica en duid<

Geen enkele drukker mag, om zichzelf te behoeden voor h Geen enkele drukker mag, om zichzelf te behoeden voo

zetwerk, tegen beter weten in gedogen dat, in het veronders zetwerk, tegen beter weten in gedogen dat, in het verond

gedaan wordt aan logica en duidelijkheid door enige typogi gedaan wordt aan logica en duidelijkheid door enige typi

in een driehoek wringen, hem in een hokje persen, hem t( in een driehoek wringen, hem in een hokje persen, hem te

zandloper of een ruit heeft, is een zonde die meer rechtvaar loper of een ruit heeft, is een zonde die meer rechtvaardig

Geen enkele drukker mag, om zichzelf te behoeden voor het vei Geen enkele drukker mag, om zichzelf te behoeden voor het verwijt van eenton

tegen beter weten in gedogen dat, in het veronderstelde belang va dat, in het veronderstelde belang van verliering, geweld gedaan wordt aan logi

logica en duidelijkheid door enige typografische buitensporighei< spongheid. Zijn tekst in een driehoek wringen, hem in een hokje persen, her

hem in een hokje persen, hem tc martelen tot hij de vorm van een een ruit heeft, is een zonde die meer rechtvaardiging behoeft dan het bestaan v

die meer rechtvaardiging behoeft dan het bestaan van hetzij italiaan ncndc en zcstiende ccuwen of de zucht ices nieuws te doen in de twinrigstt Dit

en Zestiende eeuwen of de zucht iets nieuws te doen in de twintigs en wij hebben er zo veel van geñen gedurende de voorbije 'wederopleving va

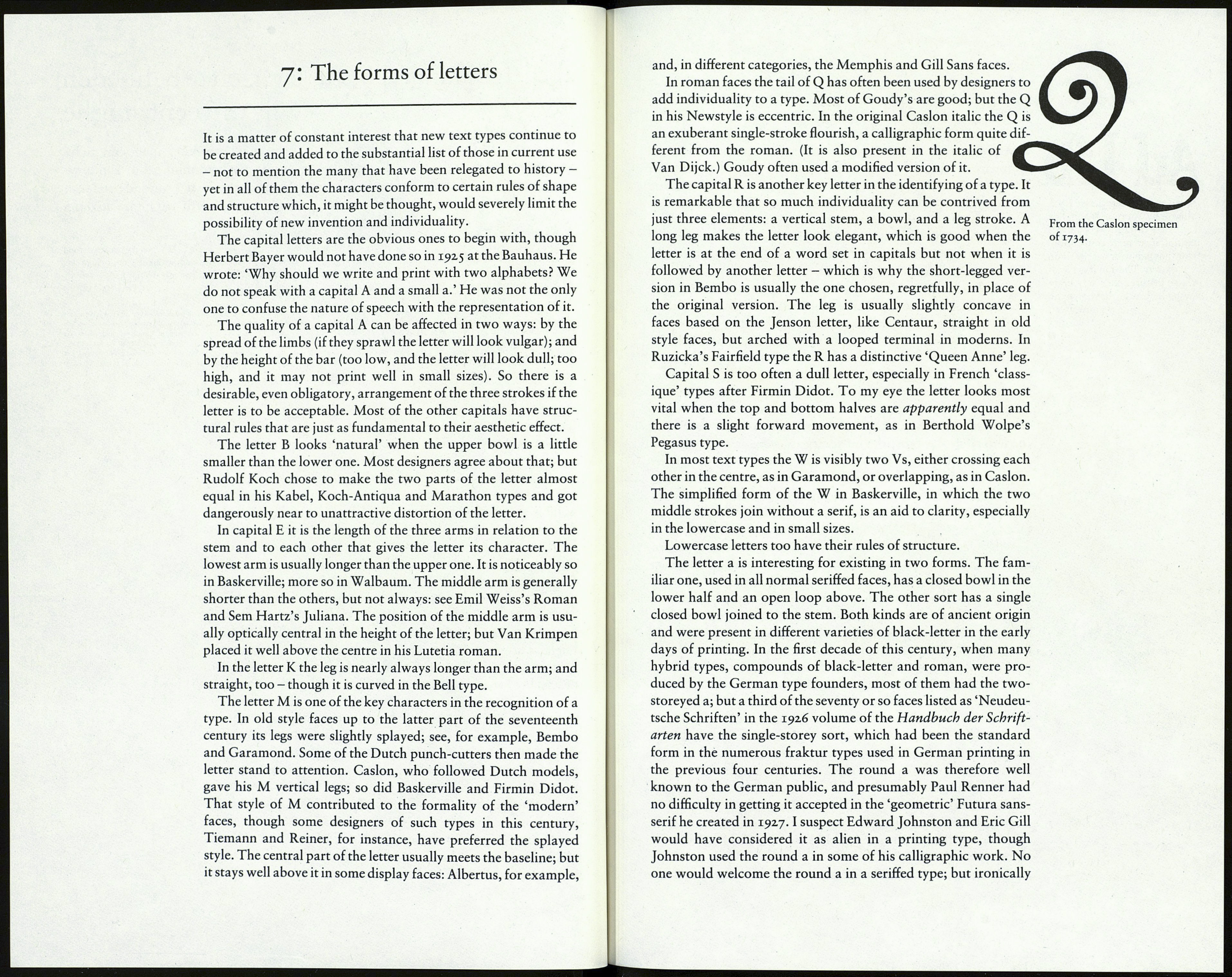

Monotype Bembo, 24, 12, 8 and 6 point: left, the metal version, right, a film version

choice that makes the larger sizes appear clumsy. The Bembo

face, an admirable example of optical compensation by the

Monotype drawing office, demonstrates the point. In the speci¬

mens of the metal version shown here the modifications of x-

height and lowercase letter widths up and down the size range

can be discerned by the sensitive eye. In the other version the 8

point is almost identical, but three of the sizes were obtained by

direct projection from the 8 point, instead of the separate masters

available. The 6 point is obviously less effective than the metal 6

point; and the 24 point, where the characters are precisely three

times the size of the 8 point, is distinctly less elegant than the

original. (The effect on the italic can be imagined.) It would be a

comfort to be able to say that that kind of thing never actually

happens. But a new work by a distinguished novelist, printed in

England as recently as 1983, has chapter headings in 24 point

Sabon italic which sprawl deplorably, for the same reason.

(Tschichold would have hated such ill-treatment of his design.) It

is not an isolated case.

Although there are few faces that have the modest x-height and

long ascenders and descenders of Bembo, automatic sizing inevit¬

ably impairs all faces to some degree. Modern designers, creating

faces for electronic typesetting, avoid the worst effects of it by

organising the proportions of their characters as a compromise

between the ideal and the necessary. But it is a compromise. Not

until the suppliers of high-resolution fonts adopt the principle of

separate masters, each proportioned for a narrow band of sizes,

will their claim that their faces are superior to the metal versions

be justified in all respects.