-48- designed to make the best of its limitations. This aesthetic argu-

Aspects ment would not be necessary if people would abandon the as-

oftype design sumption that a type of high quality or popularity (not the same

thing) should be available in its own name in any kind of output-

ting system, however degraded the result. I do not see that the

matter is affected by a printer's requirement for a high-resolution

face for final output and a low-resolution version of it to be used

for high-speed proofing only. In that case the proofing version

need not strive to be a look-alike; a 'rough' version is sufficient.

Experienced editorial people are quite willing to work with a

crude-looking proof, so long as the character count is identical

with the type face actually to be printed.

6: Proportion

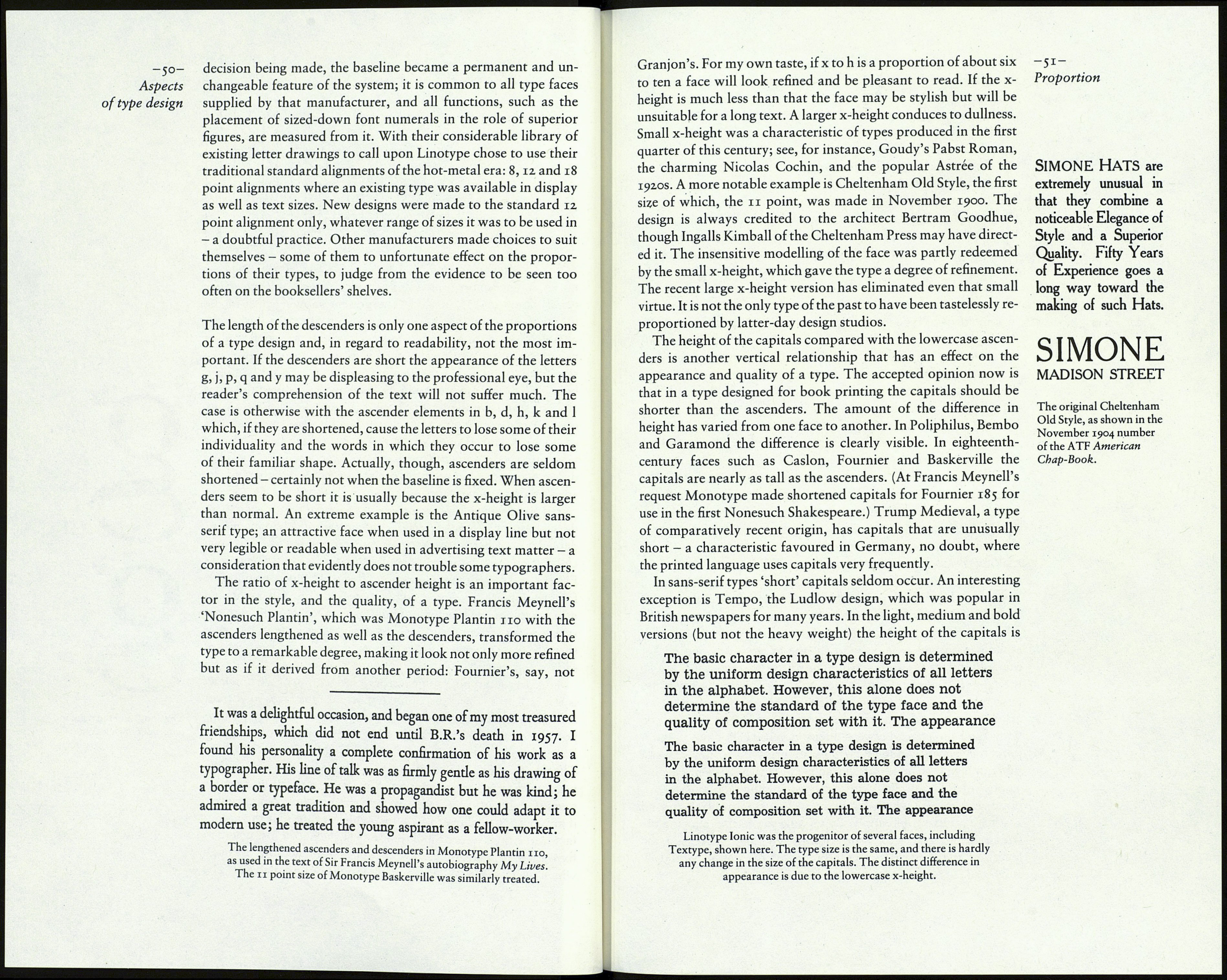

The point system of type measurement produced benefits of vary¬

ing significance. One of them, the fact that types and spaces from

different foundries could be mixed together in a line with impun¬

ity, diminished in importance as the use of mechanical compos¬

ing machines increased and the printer became, in effect, his own

type founder. What continued to be an important benefit was the

fact that types of different sizes could be placed together on the

basis of simple arithmetical adjustment: the initial letter at the

beginning of a chapter, the price at the end of a two- or three-line

description in a store advertisement, and so on. And there was

another improvement: In the early years of this century the new¬

found pleasure in the benefits of regularity and dimensional

stability induced the founders to re-cast their types on common

alignments, so that all their romans and their clarendons, bold

latins and antiques (the 'related bold' being yet to come) would

line together accurately and so eliminate the former haphazard

effects of uncalculated baselines. This offshoot of the point

system was called 'point line', which meant, in the words of one

founder, 'that the distance between the bottom edge of the face of

the type and the bottom edge of the type body (in other words,

the 'beard') measures a definite number of points, varying ac¬

cording to the size of the body'. The diagram accompanying that

description showed that the benefit sought for was the easy justif¬

ication of one size with another. It is clear, though, that the effect

on the proportions of the letters must have been crude and ill-

balanced - the length of the descenders in 8 point, for instance,

being proportionately greater than in 10 point, the reverse of

what is visually desirable. Bruce Rogers thought nothing of point

line. Referring to the so-called Fry's Baskerville, which he ad¬

ii

-49-

10

II

12 i

14

16

18

20

24

J0

36

42

48

54

Я

e 1

1

1

•i

■2

■1

■2

:і

:і

.4

:'

»

t

O

ч

м

io

1 1

12

14

Point line. From a Stephenson Blake specimen book, 1915.

mired, in his Report on the Typography of the Cambridge Uni¬

versity Press (1917), he said 'The present showing of it in the

founder's specimen sheets suffers . . . from having recently been

altered to standard line, a most pernicious practice when applied

to any type and particularly the old style ones.' However, the

significant thing is that the idea of standard alignment had been

born. When the American Linotype company adopted the prin¬

ciple of standard alignment about 1913 each size was given its

own baseline position to which all their subsequent type faces

conformed. Unfortunately, the taste of the time being what it

was, the standard alignments were fixed too low for the kind of

descenders which came to be desired by book designers in the

1920s and 30s, when types of the past were being studied, appre¬

ciated and revived. Linotype therefore found it necessary to pro¬

duce alternative 'long' descender characters (which really means

descenders of better proportion than the regular sort) in such

classic types as Garamond and Janson, and also in Dwiggins's

Electra and Caledonia. George W. Jones, who was responsible

for the English Linotype company's Granjon, Georgian and

other distinguished revivals, would have nothing to do with the

standard alignments, and insisted that the baseline in his types

should be so placed as to ensure that the descenders were of

satisfactory length.

This detail of typographic history, the location of the baseline,

is relevant to the present. Some important type faces in current

use owe a significant aspect of their appearance to rules of pro- упе <[ong> an¿ t^e regular

portion established at a time when the scope of typographic descender in Caledonia,

knowledge was limited and the standard of design was low.

The faces needed the attention of a discerning eye before they

were transferred to filmsetting. Electronic typesetting systems

measure 'film advance' - that is, type size plus inter-line spacing,

if any - from baseline to baseline, which meant that the manu¬

facturers of the systems had to decide at the outset just where to

fix the baseline in the vertical aspect of the 'window' through

which the type would be transmitted to the output material. The

g

g