~44~ and there is much more to be done. When the full alphabet has

Aspects been scanned the result is printed out. The characters must now

of type design be 'edited' by someone with an educated eye. He or she studies

each sample letter carefully and marks out unwanted picture

elements ('pixels') and marks in extra pixels where a curve or

diagonal stroke needs improvement. The edited proof is handed

to an operator who calls each character out of memory and on to

a screen, and then proceeds to key the corrections. When all the

corrected characters are back in font store they have to be tested

at actual print size and, if necessary, revised again. The process is

time-consuming and expensive in inverse proportion to the reso¬

lution. In a type digitised at 1200 lines per inch the em square of a

12 point master contains 40,000 pixels and the contour of the

letter on the sample will be fairly close to that of the original

design. The amount of manual editing and correction will be

much less than for a type digitised at 600 lines per inch, where the

12 point em has 10,000 pixels and letters like a, s and w will show

stepped edges which need a good deal of attention. In. the case of a

type intended for use in a small size, such as a newspaper classi¬

fied advertisement type or a telephone directory face, digitised at

600 lines, the 6 point em has 2,500 pixels: that is, 50 by 50, which

on the proof sheet makes a distinctly gingham effect and needs

much work by the editor and corrector before the array of char¬

acters can safely be put into memory store as the master font

ready for copying for the user. To reduce the labour time and the

amount of data which has to be stored for each character, other

methods have been devised. In one of them the letter is related to

a pattern of lines equivalent to the tracks of the writing spot, and

the beginning and end of each line where it meets the contour of

the letter is plotted and recorded, the writing spot in the typesett¬

ing system 'filling in' the outline at the output stage. The analysis

of the character shape takes more time than sample scanning, but

the method reduces or eliminates editing and correction, and the

memory requirement is much less than in the first method,

though the processing is more elaborate. In another approach the

profile is 'converted' to a sequence of vectors, and their junction

points are recorded; the computer in the typesetter is program¬

med to connect the points and fill in the outline. In all such

methods (and there are others) a good deal of time and effort by

skilful people has to be put in to the editing and correcting of

samples or the analysing of characters for special digitising to

work with special programs, so it is not surprising that more

sophisticated methods of scanning and automatic contour plot¬

ting are in active development.

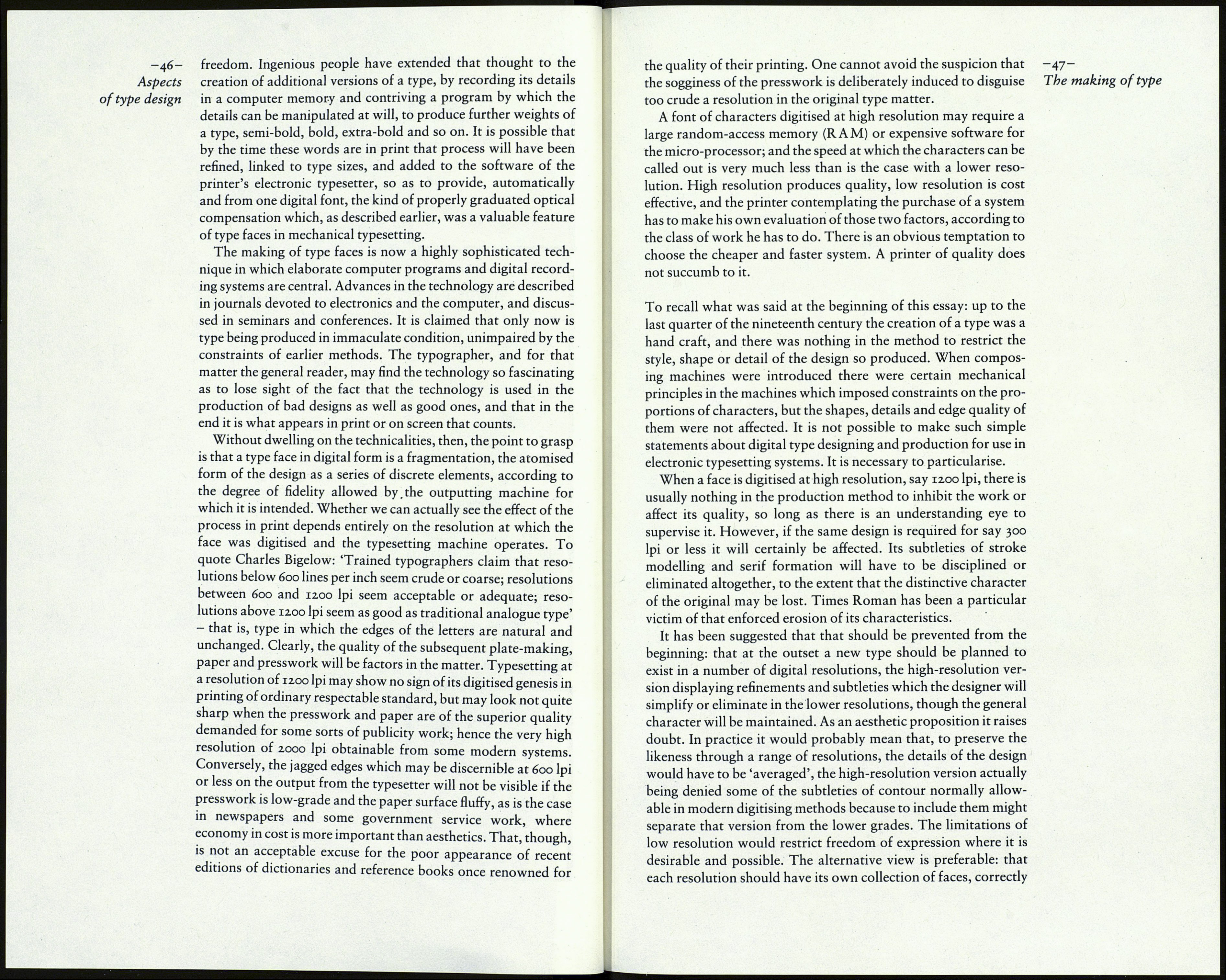

The intention in editing and correcting a digital sample is, of

course, to repair and restore the character; but the process itself

can be thought of as manipulation - the adding or subtracting of

bits to the edges of letters with, usually, a considerable amount of

Digitising.

A letter in its natural form, as it would appear in

metal type or on the film font or disc in an opto¬

mechanical photo-typesetter.

A simplified representation of the letter when it is

automatically scanned and converted into digital

pixels. Every pixel is stored as a code in the

computer's memory.

(In reality, the pixels, and the lines in the next

example, touch or overlap each other).

The amount of data to be stored is much less

when the letter is 'run-length' scanned, as in this

example. Only the start and stop of each scan line

is recorded - an economical means of storing the

data for large sizes of type, though processing the

data is more complicated.

For even more economical storage the profile of

the letter can be imagined as a series of vectors

(line or arc), their connecting points being selec¬

ted by an operator plotting them into store. A

special routine in the computer's processor con¬

nects the points and fills in the letter shape at the

output stage.

Those are simplified examples of basic methods

of digitising. Computer technology advances so

rapidly that the digitising of characters is now a

highly sophisticated process which, at high reso¬

lution, leaves no trace of itself in the printed

output.

99924