-42- the result was a perfect facsimile of the character, in clear on a

Aspects solid background. Because red acts like black in black-and-white

of type design photography this 'frisket', as some people call it, served as a

negative, which could be placed in a sophisticated version of a

process camera and shot into a prescribed position on a film

positive. When the full array of characters had been dealt with

the result was a master font, from which copies would be made

and supplied to the user of the composing machine. That, or

some variation of it, was the method by which the established

composing machine manufacturers made direct use of their tried

and tested type face artwork in the transfer from metal to film -

or hot to cold, as the phrase has it.

The first kind of electronic typesetting system was called a

'photo-typesetter'. The 'photo-type' part of the term is an in¬

dicator of both the physical form of the character array in the

machine, the font strip or disc, and the way the characters were

transferred to the film or bromide paper output material: that is,

through a system of lenses in a version of traditional photo¬

graphic practice. Note that the type faces made for such machines

derived directly from the original letter drawings, and what ap¬

peared on the output was simply a sequence of photographs of

the letters as they were drawn at the beginning of their existence.

That is not strictly true, perhaps, because for a time there were

those who believed and practised the idea that the angled corners

of counters - for example, where the bar in H meets the uprights

- should be notched, to compensate for the tendency of the

photographic process to round off the angles (that is, when the

lenses in use were not of the best quality). But that practice, which

was soon discarded, was intended to preserve the original state of

the design, not to modify it in any way. However, in the other

kind of electronic typesetting system that established itself in the

early 1970s the abrasion of the edges of characters became a new

feature of typography and a cause for concern, especially in the

appearance of large headlines.

Machines of the photo-typesetter kind are opto-mechanical;

the font is a spinning disc, or there is a moving grating to select

the character to be exposed, or there are other moving parts.

Movement takes time, and puts a limitation on the scope and

speed of a machine - and speed of output is what most printers

want; hence the other sort of machine, in which the optical lens

system was replaced by a cathode ray tube, a sophisticated ver¬

sion of the object that forms the screen in the familiar television

receiver. In the first CRT machines the character font was still in

the form of a photographic negative. The machine contained a

scanning device, a light spot which traversed the characters, its

responses to the profiles of the letters being recorded in the buffer

in the computer. When the line of text was completed the signals

were released and the characters were 'painted out' by the cath- —43 —

ode ray tube - the letters being formed, so to speak, by slices of The making of type

light. That is a very simplified account of a complicated sequence

of events; but the point of it is that for the first time the profiles of

the characters are being interfered with — or, as some would say,

degraded. Scrutinised under a magnifying glass it is possible to

see that the curved and diagonal strokes have become stepped,

the size of the step being precisely that of the light spot. In en¬

largement the effect is displeasing, but the thing is entirely relat¬

ive - the width of the writing spot and the type size being the

deciding factors as to whether the effect is noticeable in print.

With the machine working at, say, 1000 lines to the inch, when

the light spot is only one-thousandth of an inch in diameter, the

stepped effect is not visible to the reading eye even at quite large

sizes. At 600 lines to the inch (when the output is very much

faster) the 8 and 9 point text in a newspaper looks normal

enough, though that is too coarse a resolution for headline sizes.

As soon as CRT became a feature of electronic typesetting

systems 'resolution' became an important addition to the

printer's vocabulary. It refers to the edge quality of the letters;

and suitably qualified as 'high', 'medium' or 'low', it indicates the

extent to which the contours of the letters look 'clean' to the eye,

and therefore the extent to which the subtleties of the original

design have been preserved.

Of the various sorts of writing spot in use CRT has continued to

be the outputting method in most electronic typesetting systems,

though some important machines use a laser beam. The intro¬

duction of CRT and laser into typesetting technology were con¬

siderable advances; but the replacing of the photographic font

negative by the digitising of characters has been an even more

radical step, and one that has produced problems as well as ad¬

vantages. The motive for digitising is easily stated. By converting

the type characters into little bits and recording the bits as

electronic signals which can be stored on a disc as an adjunct to

the computer, they can be called out in intelligible shape by

the modern micro-computer at a speed which could not have

been imagined a few years ago, and with an edge quality of con¬

siderable refinement - though that has to be paid for.

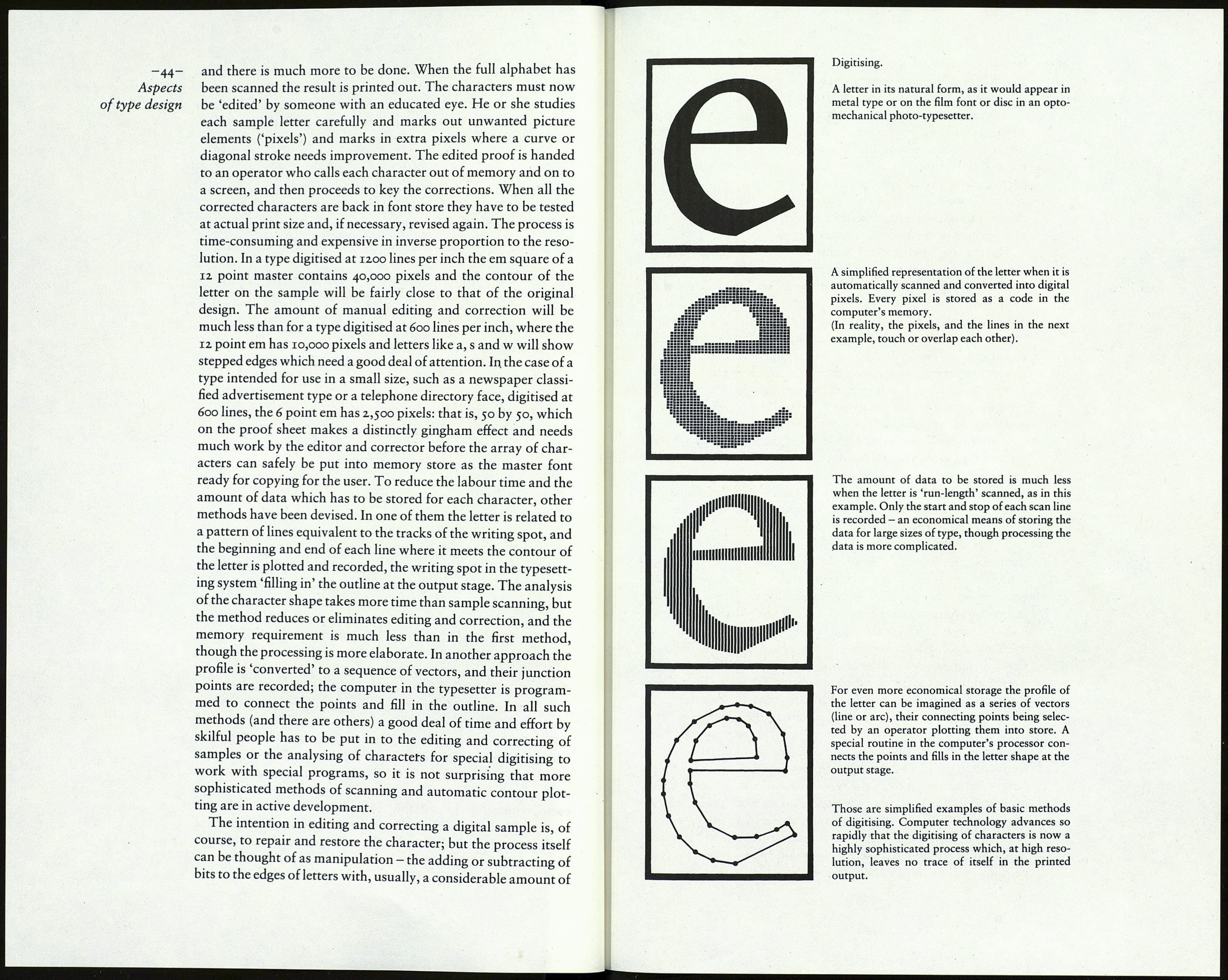

The method of digitising is the cause of one of the things that

make type production, and in some cases type designing, much

more complicated than formerly. Actually, there are several

methods. In one method the frisket or enlarged solid image of

each character is passed through a sensitive scanning device

which reads and records the character on a grid, in which the size

of the basic element is related to that of the writing spot that will

paint out the character on the output material. What comes out

of the scanning process is a 'sample'. It is only the beginning