-38- writing in 192z] in type cut by machine is undeniable . . . This

Aspects improvement, I learn, has come to pass through a more sym-

oftype design pathetic and subtle manipulation of the machine itself, and by

modification of rules by the eye of the workman who operates it.'

Jan van Krimpen, too, made much of 'the problems' of mech¬

anical punch-cutting in his Letter to Philip Hofer (a sadly

muddled work whose chief merit is that it caused John Dreyfus to

write a very interesting commentary on it). Updike and other

critics disapproved of the 'mechanising' of letter forms, by which

they meant the eliminating of 'the slight irregularities which the

human eye and hand always leave in manual work', which Van

Krimpen thought were 'an important element of the charm of

hand-cut type'. It may be that it was not so much the accidental

imperfections of execution that these critics admired in the types

of the masters of the past as the subtleties of style which the

designer-punch-cutters had deliberately introduced into their

faces. In their comments they show no sign that they recognised

the different kinds of punch-cutter - though one of them, Bruce

Rogers, had a sense of that when, speaking of his Montaigne

type, he said, '. . . partly through the conventional training

of the punch-cutter (who was nevertheless a most admirable

and skilful workman), the desired quality was only partially

attained'. And it seems, from the way the critics expressed them¬

selves, that they had an imperfect understanding of the way type

designs for mechanical composition were produced. The work¬

men who operated the pattern-making and punch-cutting mach¬

ines did not, because they could not, alter the letter forms in any

way. That was the province of the drawing office, where, from

a projection of a character on a type proof or from a designer's

original drawing, the 'ten-inch' drawing was produced. Insensit-

ivity in that area was not unknown. In 192.1 Goudy had cause to

complain about the treatment of his Garamont design. 'Draw¬

ings like mine, which were made free-hand, were not the sort

usually worked from at the [American] Monotype company, so

there was a constant fight to see that the workmen did not

"correct" what seemed to them to be bad drawing on my part. If I

intentionally gave a letter an inclination of one degree, they

straightened it up. My serifs, which had a definite shape, were

changed to meet their own ideas, since "they had always made

them that way".' But if the work of the type drawing office was

under the supervision of someone with a good eye for a letter, as

was the case, for example, in the Linotype companies and in the

English Monotype office, the letter drawings would show either a

faithful replica of the original or a modification of it in accor¬

dance with a premeditated view of the desired result. There is

ample evidence of the care that was given to the reproduction of

designs, old and new, to preserve the character of the face and to

make it suitable for the requirements of modern printing. For

example, when sending a proof of Linotype's version of the so- -39-

called Janson type to Carl Rollins for comment on 18 January The making of type

1932, C. H. Griffith wrote, 'I hope you do not mind my bothering

you so much with this proposition, but I am so anxious to have

the Linotype face worthy of its name. If I cannot succeed in

satisfying myself that our interpretation of Janson will be worthy

of the honored name it bears, we shall not hesitate a moment to

scrap the whole work and forget it.' And there was the solicitous

handling of Granjon and other revivals by Harry Smith at Altrin-

cham in collaboration with G.W.Jones; and Fritz Steltzer's

expert supervision of Monotype's Ehrhardt, a radical adaptation

of the Janson face. Those examples could be multiplied. Stanley

Morison was unfair to his colleagues when he wrote in A Tally of

Types, 'Virtue went out with the hand-cutter when the mechanic

came in with his pantograph and the rest of the gear.'

However, there were certain aspects of type face manufacture for

mechanical composition which potentially had a bearing on the

appearance of type. One of them was due to the punch-cutting

machine itself. Since it worked on the pantographic principle and

had the facility of fine adjustment it could produce several sizes of

punches from a single pattern. In practice, though, the manu¬

facturers had the sense to see that restraint was needed if their

type faces were to compare favourably with foundry-made types,

and they accepted the fact that they must continue the traditional

practice of 'optical compensation': that is, the modifying of the

lowercase x-height and letter widths to maintain legibility in

small sizes and elegance in the larger ones - an important subject,

to be enlarged upon in a following essay.

nn

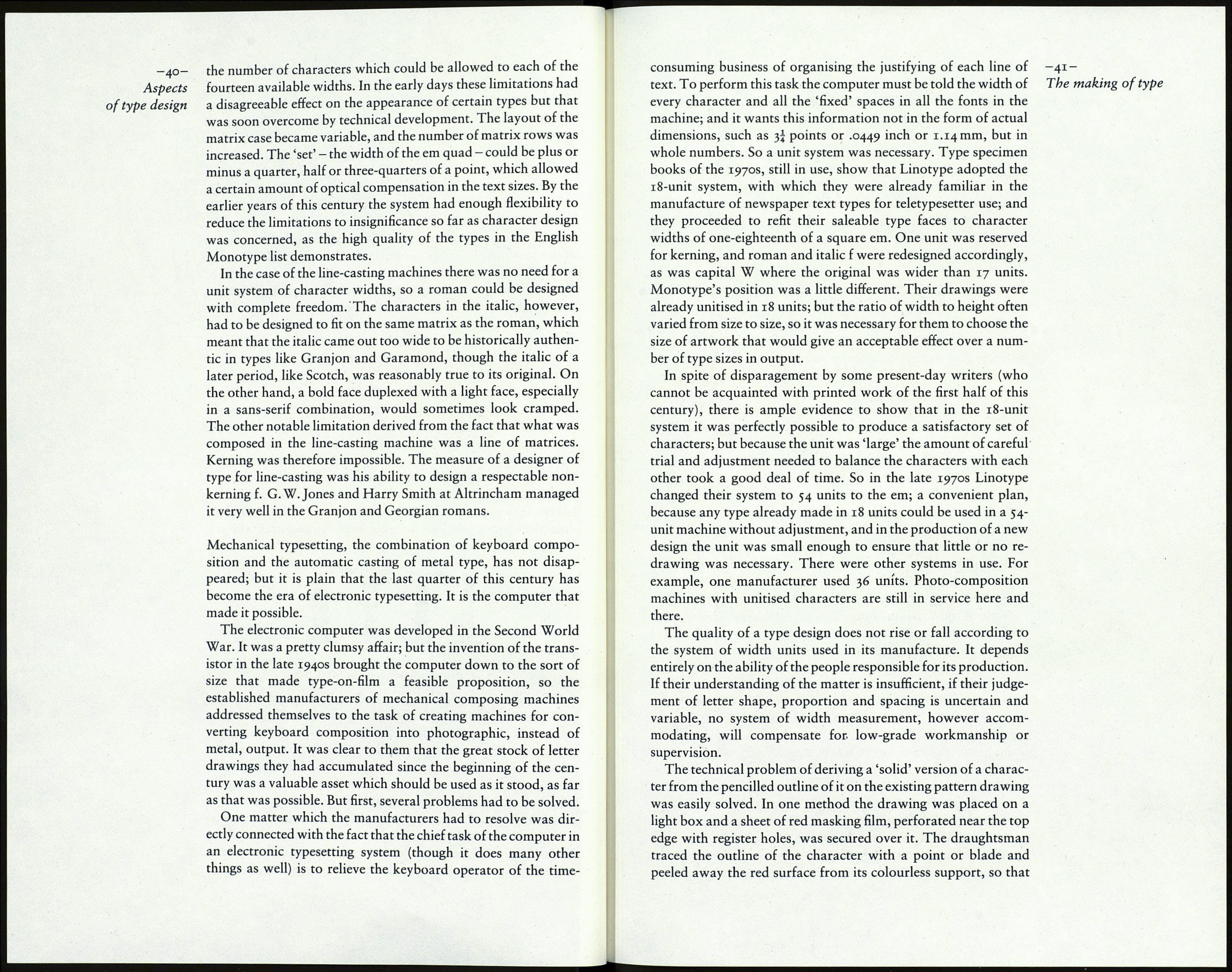

Optical compensation. A letter from the 12 and 8 point sizes

of Caledonia, enlarged to the same type size.

There were constraints in the Monotype system which at first

sight seem severe. The system had two parts: a keyboard whose

output was a ribbon of perforated paper, the perforations repres¬

enting codes for the characters and for the justifying of the lines;

and a casting machine, driven by the ribbon, which contained a

metal pot and a die-case - that is, a frame holding the matrices in

rows, an equal number in each row. The first constraint was the

fact that the width of every character, including its own side

spaces, had to be equal to a multiple of one-eighteenth of the

width of a selected em quad, five eighteenths being the minimum,

eighteen the maximum. The second constraint was the limit on