-34-

Aspects

of type design

Punch-cutting.

From Karl Klingspor's Über Schönheit von

Schrift und Druck (1949),

by kind permission of

D.Stempel AG.

other crafts.) When a sufficient number of castings had been done

the pieces of type were assembled in line, their feet cleared of

extraneous metal and identifying nicks were grooved into the

shank. Note that in this series of tasks the punch, so laboriously

produced, was not an end but the means to an end: the matrix

was the indispensible item.

That was the method of type making used for types as diverse

as the textura of Gutenberg's work, the romans made for Aldus

(one of them we know today as Bembo), Robert Granjon's

remarkably elaborate Greek type, his Civilité, the delicately

complicated Union Pearl of about 1700, Firmin Didot's austere

modern face, and many of the nineteenth century 'fantasy' types

- to mention only enough to show what a variety of design was

achieved by the skill of the punch-cutter during the long period

when printing was done by hand and eye, and not by any sort of

machine. It is clear that, as a means of creating a letter, the act of

shaping a punch had no particular influence, and enforced no

limitation, on the style or shape or detail of the character. Letters

could be any width, angles and serif ends could be as sharp as

desired (because the metal was being cut away, not incised), and a

modification to the mould allowed letters to be provided with

kerns; in short, the skilled punch-cutter had fewer limitations in

his creative work than was later the case in the making of type

faces for mechanical composition, as we shall see.

It was the punch-cutter himself who, if he possessed artistic

sense as well as manual skill, was capable of influencing the

appearance of a type - indeed, of creating a new effect altogether.

Thus the types cast from the matrices struck from the punches cut - 3 5 -

by Claude Garamond owe their distinctive appearance to his The making of type

creative sense, his vision of the style of face he wanted to produce.

The same can be said of Kisand Caslon, Fournier and Firmin

Didot, and many others. They were designer punch-cutters.

Baskerville is a different case. He had the vision; but his punches

were cut for him by John Handy, who can be called an interpre¬

tive punch-cutter. There have been others such: Edward Prince,

who brought into being the ideas of Morris and Cobden-

Sanderson; Charles Malin, who was engaged by Stanley Morison

to cut punches of Gill's Perpetua design before Monotype took

up the work; and P.H.Raedisch, who interpreted the designs of

Jan van Krimpen. Most of the men who worked for the

nineteenth-century American foundries were punch-cutters of

the interpretive sort, able to receive a sketch or note for a new

type and give its characters style and coherence. As William Loy

wrote in 1898, 'Very few engravers of type faces work from their

own designs; indeed, the qualifications are so dissimilar that one

would hardly expect to find them in the same individual.' No

doubt there was a third class of punch-cutter, the artisan kind,

employed not for any ability as designer or interpreter but for

manual skill and accuracy — which must have been considerable,

to judge by the 'finish' of the faces shown in the later nineteenth-

century type founders' catalogues. The seven or eight punch-

cutters in the Mergenthaler plant in 1890 were probably of that

sort - their task being to cut punches for newspaper text types in

imitation of existing founders' faces, but more particularly, to

replace the punches which broke so frequently.

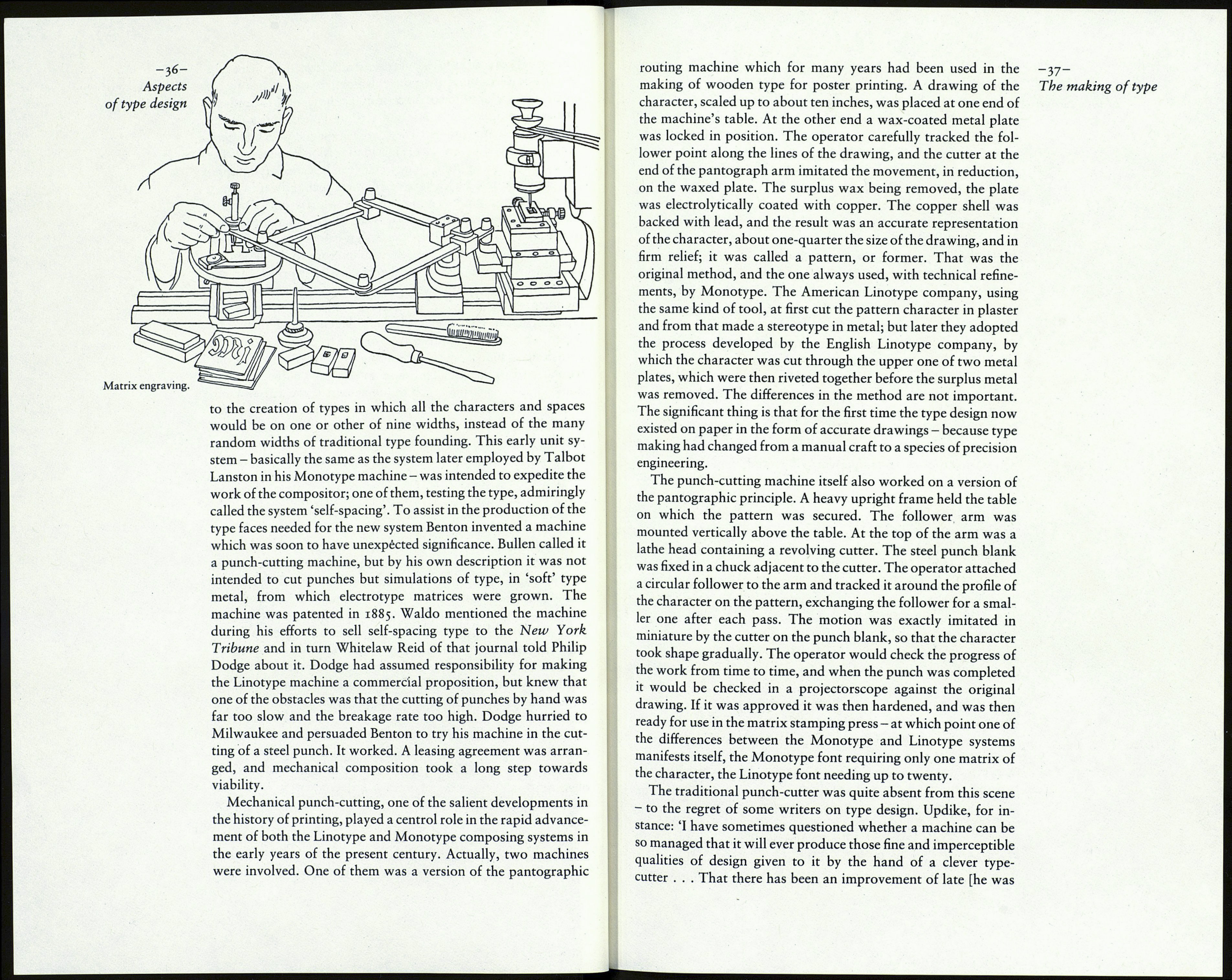

In type founding as elsewhere the invention of steam power

made mechanisation possible. A machine for the rapid casting of

type was developed early in the nineteenth century. Towards the

end of that period some type founders adopted, as an alternative

to punch-cutting and matrix striking, the engraving of the char¬

acter directly into the matrix blank - a method only suitable for

fairly large sizes and for designs in which rounded angles, caused

by the powered rotating cutting tool, were tolerable. (More of

this later, when the work of Frederic Goudy is examined.) Yet

another method, the electrotype matrix 'grown' from a pattern

cut in 'soft' metal, was an easy way of producing a new type face,

and one of the reasons why the last quarter of the nineteenth

century was such a prolific period. The most significant event,

though, was the mechanising of punch-cutting. It removed an

obstacle to the progress of mechanical typesetting, and was

thereby the indirect cause of the decline of type founding as a

trade.

The unwitting instigators of the event were Linn Boyd Benton

and his partner R.V.Waldo. They conducted the Northwestern

Type Foundry in Milwaukee, where Benton devoted his energy