-32-

Aspects

of type design

newspaper text type was designed for high-speed production

methods which do not allow for much finesse. A stronger reason

is that in the editorial columns of newspapers we prefer the text

and headlines to be set in plain matter-of-fact types, and in books

we want faces of refinement and distinction. Set a novel in a

newspaper type and the effect will be so uninviting that the

success of the work will be jeopardised. Set a newspaper in a

book type and we will not take it seriously. (There was once a

newspaper which used Caledonia for its text. That excellent

book type helped the paper to gain awards for good design but,

ironically, contributed to its early demise.) So as well as the func¬

tional aspects of type design there is the aesthetic aspect; and it is

the proper balancing of the functional and the aesthetic which we

look for in the work of the type designer, just as we do in other

fields of product design.

5 : The making of type

Electronic typesetting has now had a dominant place in printing

technology for a fair number of years, and there has been ample

evidence of the high level of fidelity which a capable manufac¬

turer can achieve in reproducing the subtleties of type faces (and,

for that matter, too much evidence of what an insensitive

manufacturer can perpetrate). Yet some writers on typography

continue to assert that the change from mechanical typesetting

to systems comprised of electronics for their power and

photographic chemistry for their product requires some sort of

change in the design of type faces, without specifying what

kind of electronic typesetting they have in mind. It is true that

low-resolution systems impose severe limitations on letter form

and detail; but the high-resolution systems used for most of

the printed matter we read allow the type designer as much free¬

dom as he is likely to need, and can reproduce his work to a

remarkably high standard.

The belief that the method of manufacture has an influence on

the design of type is not new. There is little justification for it. In

fact, the history of printing types is a tale of sophistication in

letter design being achieved at quite an early stage, reaching

heights of ingenuity in the nineteenth century, and not being

affected to any noticeable extent by the techniques of manu¬

facture.

To examine that point, and bearing in mind that a large num¬

ber of types in use at the present time were created before the

advent of electronic typesetting - and some of them even before

the invention of mechanical composition - an outline of the sue- - 3 3 -

cessive methods of manufacture may be useful. The making of type

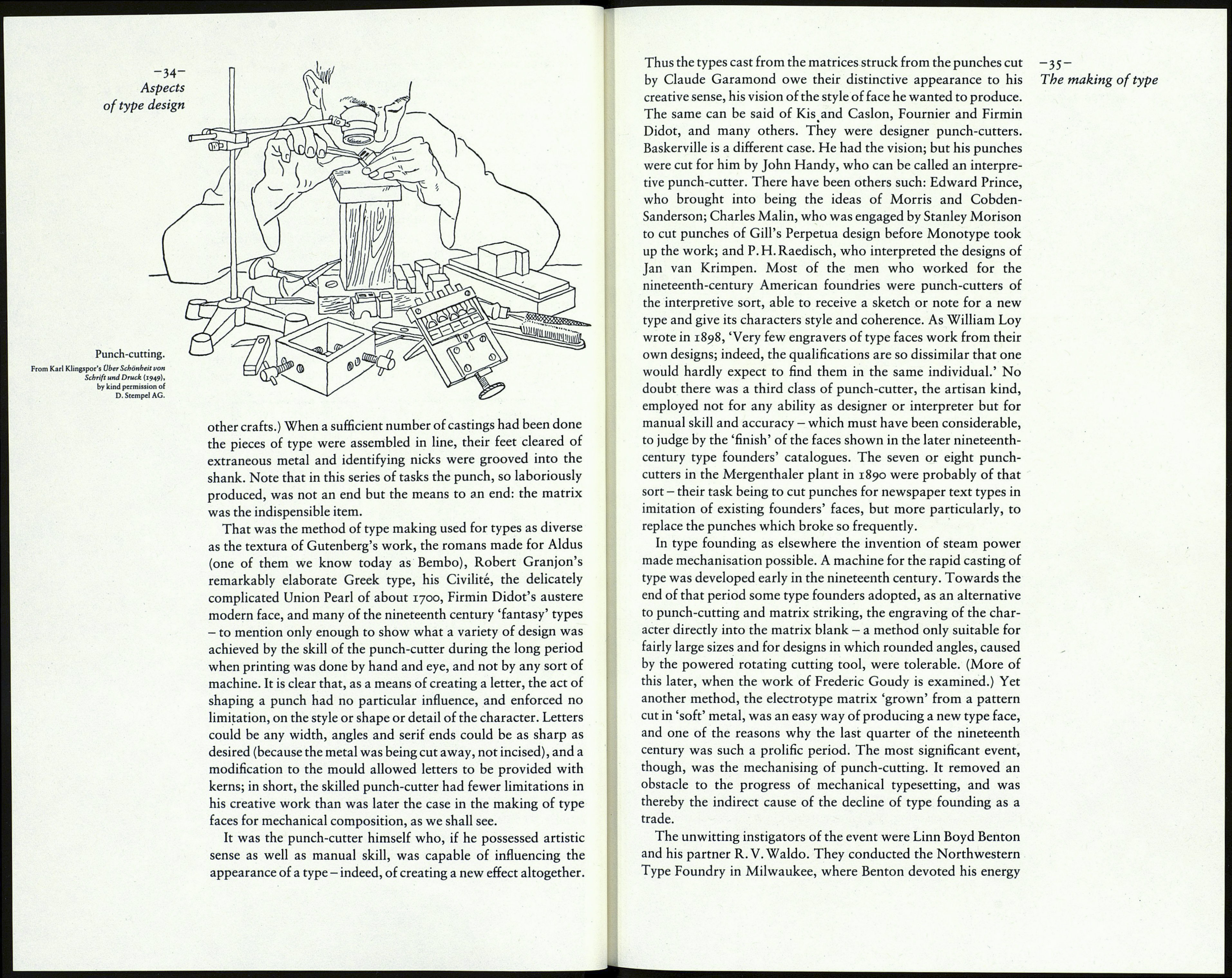

For four hundred years, from the middle of the fifteenth century

when printing in Europe began, the making of type was a com¬

bination of four hand crafts: the cutting of letter punches, the

striking of matrices, the casting of the type, and the dressing of it

ready for use by the printer. Each of them was essential, but only

the punch-cutter's work displayed itself to the critical world.

The punch was a short bar of annealed steel, the end of which

was to be shaped to the form of the character. For any letter that

contained an interior enclosed space, such as В, O, a, g, the

punch-cutter would first make a counter-punch to the shape of

the interior white area - hence the term 'counter' for that part of a

letter. The counter-punch would be driven into the face of the

punch, and then the outer profile of the letter would be formed by

filing away the unwanted metal; slow painstaking work, with

many pauses for the checking of the size of the letter and the

thickness of its strokes with a variety of specially-made gauges.

Gunter-

counter-

purtrij

iii

J:sssr

ill

i*1

The counter-punch.

When the letter was finished the punch would be held in the

smoke of a lamp or candle flame until it was blackened, and then

pressed on to paper so that its image could be compared with

other characters of the font. If it was satisfactory the punch was

hardened. It was then struck into a small bar of copper, which

thus became a matrix. It had to be justified, its sides rubbed down

to remove the displacement caused by the strike, its face lowered

until the depth of strike was correct. The matrix was then passed

to the type caster, a skilled workman whose tool was the mould,

the ingenious device in which the matrix was fixed so that the

letter was at the bottom of an aperture adjusted to the size of type

required. Molten metal was poured in to form the piece of type.

(As A. F. Johnson pointed out in his Type Designs, the mould was

the essence of Johann Gutenberg's invention in printing, not

punch-cutting or the press, both of which were already known in