-28-

Aspects

of type design

ENGLISH ITALIAN

POR 1824.

The fat face turned inside out. The full point

defied the treatment.

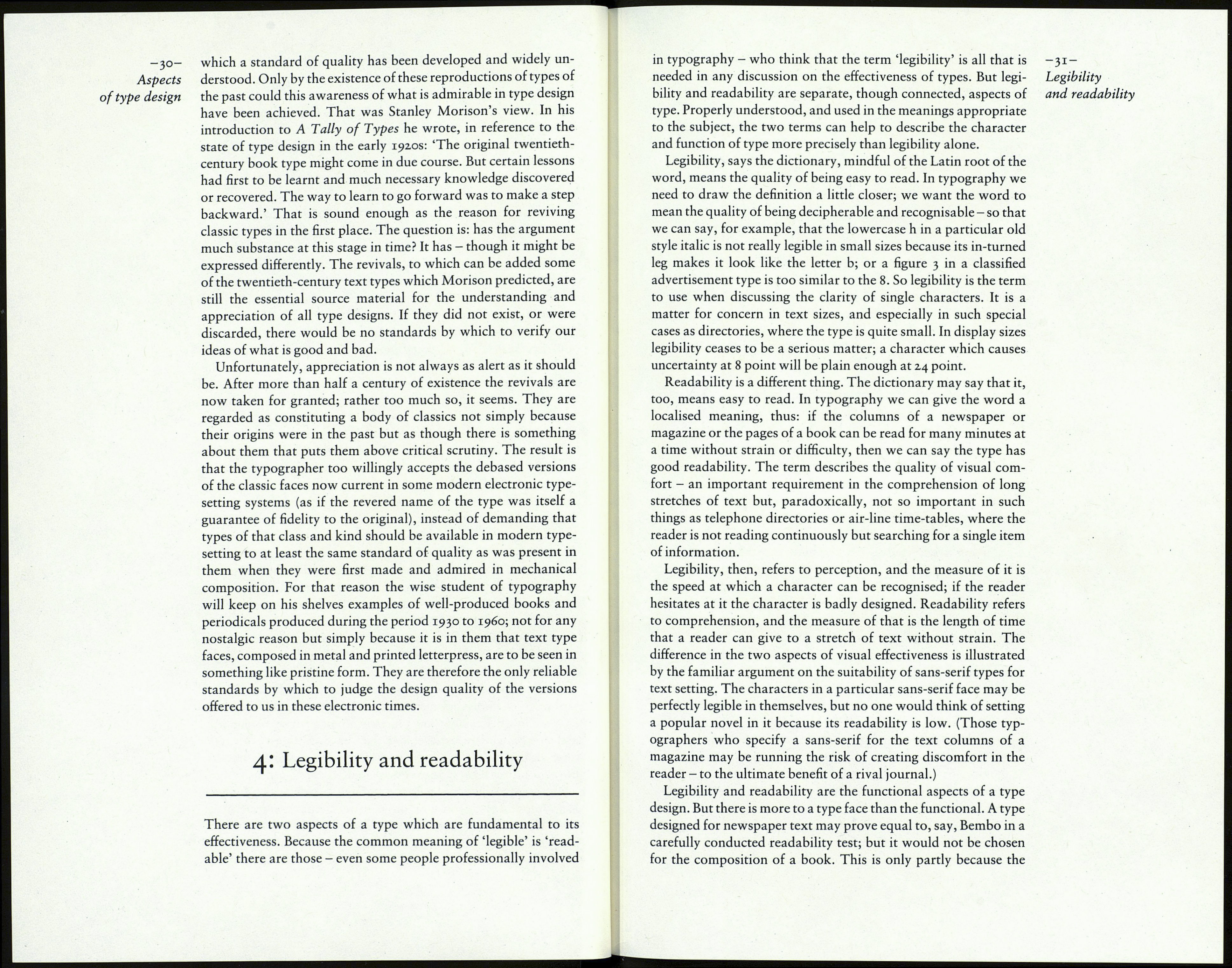

said, a maltreated egyptian. I think it was an exercise in ingenuity

by a lively-minded person who, knowing that the 'fat face' -

which was the modern letter that had, as the song says, gone

about as far as it could go - had astonished the printers, decided

that the shock could be repeated if all the characteristics of the fat

face were reversed - the thick strokes made thin, the thin strokes

and serifs made thick, tapers inverted, and so on. The Italian face

was г jeu d'esprit, not meant to be judged in conventional aesthe¬

tic terms. Even more ingenious are the recent Block Up and

Bombere faces, which exploit the illusion of an extra dimension,

Block Up and Bombere.

and Stop, which is more subtle than it seems at first sight. But

such types are (literally) not typical. Most publicity types stay

closer to familiar letter forms, though novelty is usually their

chief raison d'être. They are meant for the come-on line in adver¬

tising work or the brand name on a package, or in the multitude

of items generally called ephemeral printing. Such types have no

certainty of a long life, because novelty is by definition itself

ephemeral. While they last they serve a turn, adding a visual fillip

to print just as the rustic, ribbon and bamboo types did a hundred

years ago. Some of these display types are skilfully designed.

Others are heavily-promoted but dismal souvenirs of the tail-end

of the nineteenth century, which do little credit to those who use

them and none to those who revived them. Others again are

inexcusably clumsy, and only see the light of day because their

promoters know that there are advertising typographers for

whom it is enough that a type is new. (The temptation to include

here a rogues' gallery of such types has been resisted.) Whatever

their merits, publicity types are of little help to anyone attempt¬

ing to acquire a sound knowledge of typographic letter forms and

to recognise the criteria by which they should be judged. For that

purpose it is necessary to concentrate on a different area: to study

those types which from their beginning were intended to be used

in the composition of text matter - the io or n point of the

typical book, or the 8 or 9 point of the magazine or newspaper; in

other words, types designed for long stretches of reading, which

prove their merits by subtleties of detail, not by novelties of form

or flourish.

At first thought the obvious text faces to describe and analyse

would seem to be the revivals and re-modellings of the types now

regarded as the great classics of the past: Bembo, Granjon,

Ehrhardt, Caslon, Fournier, Baskerville, to name a few. Cert¬

ainly the student ought to make a careful study of the types of the

past, in their original form through the writings of Updike,

Johnson, Morison and Nesbitt, and also in the revivals and

adaptations produced in the 1920s and 30s-cautiously keeping it

in mind that type faces have not always been named accurately

and that there are important differences between, say, Italian Old

Style and an Aldine face, the true and false Garamonds, the

original Caslon and Baskerville and the 'regulated' versions of

them. However, the history and characteristics of those distin¬

guished revivals will not be rehearsed in these pages; not only

because that has been done sufficiently elsewhere, notably in

Stanley Morison's A Tally of Types, but because those types

were first created when printing was a craft, not an industry,

when the powered press and machine-made paper were yet to

come, and type faces were not so much designed as developed

from a previous model. For those reasons, then, and particularly

because type designing, as a professional activity outside the type

foundry, began just about the beginning of this century, the types

to be discussed in detail in the second part of this book will be the

creations of some notable twentieth-century designers who took

an individual view of type and recorded their thoughts about it.

To continue for a moment, though, about the revived classics:

typographers seem to have an ambivalent attitude towards them.

Like other design-conscious people they appreciate buildings,

furniture and other objects made in the past but, rightly, frown at

reproductions of them: neo-Georgian houses, Jacobean-style in¬

teriors, book club editions in pseudo-Renaissance bindings, and

so on. They decidedly want things made now to show the fact,

and not pretend otherwise. Yet they have a different attitude

towards text types - willingly, even preferably, setting a modern

novel or journal in a type that was created several centuries ago.

This is a contradiction, no doubt; but it is a necessary one. There

is an important reason why the revivals should continue to be

used. On the basis of practical experience of them and on what

has been written about them during the past sixty years it has

been possible to form a corpus of ideas about letter design from