-i8- hoped at first that a 'small cap' routine in the computer pro-

Aspects gram, by which the capitals would be automatically reduced in

of type design size, would produce a tolerable effect. It did not. The letters

came out too cramped and too light. Manufacturers who take

quality seriously now provide correctly drawn small capitals in

selected book faces.

Stem. Some writers use 'stem' for any vertical stroke in a letter. In

this work the term is used of one stroke only - usually, but not

always, the one that a scribe would write first: thus, the upright

in E and p, but not the vertical strokes in N, which are secondary

to the diagonal stroke.

Swash letters are the fancy alternatives in the italics of some book

types, Garamond and Caslon, for example - though in the latter

the swash letters, according to Caslon s Circular for Summer

1890, 'do not belong to the original founts; the first Caslon

deeming them superfluous, discarded them. They have been

recently engraved . . .' They are generally more of an affect¬

ation than an asset. They were available in mechanical typeset¬

ting but seldom used, because they had to be inserted into the

line by hand. They have almost disappeared in modern practice.

Titling. Capitals and numerals usually made to occupy all the

body size. Thus the capitals of Perpetua Titling 258 are larger

than those of Perpetua 239, size for size. The capitals of the

Times Tidings are actually smaller than those of the normal

roman and bold. See the essay on Times Roman.

TTS stands for teletypesetter, a method used chiefly in the

American newspaper industry by which news agency reports

are transmitted by wire or radio in punched code form, decoded

by the receiver in an outlying newspaper office, and converted

into punched tape which then drives the operating unit on a

Linotype keyboard for 'no hands' typesetting. The method re¬

quires the use of type faces made to a simplified 18-unit system.

Some of them appear in current lists of digitised type faces.

Unit system. A measurement formula to enable the widths of all

the characters in a font to be expressed as whole numbers. The

main unit is usually the width of the em of the type size, divided

into smaller units: 18, 36, 54, 96 units to the em are some of the

systems in use.

Weight. In this book the terms light, bold and heavy are used to

express variations from the normal weight. They are reasonable

equivalents to the German leicht, halbfett and fett, which occur

in the essay on the types of Rudolf Koch. In modern practice

Book, Medium and Black, with Extra and Ultra as supplemen¬

tary adjectives, are frequently used as additions to the scale of

weights - not always appropriately. 'Book' is hardly the right

term for Futura, a sans-serif face not used for book compo¬

sition. And help is needed to understand just what is meant by

'Erbar Extra Medium'.

x-height. The distance between the baseline and the x-line, the -19-

level of the top of the lowercase x. It usually refers to the height The vocabulary

of the lowercase as compared with the capitals, though in a of type

normal seriffed face nearly all the lowercase letters are slightly

taller than the x.

The classification of type designs is an unresolved problem. In

i860, when the Miller & Richard type foundry of Edinburgh

introduced the new face created by Alexander Phemister they

said it was superior to 'old style' types (meaning Caslon's face in

particular). Yet they named the new face 'Old Style', to the

confusion of printers in Britain, who were forced to invent a new

term, 'old face', for Caslon and the earlier book types. But all was

not clear. John Southward, a respected writer in the printing

trade, clarified the matter. In his Practical Printing (second edi¬

tion 1884) he wrote, 'The words "Old Face" and "Old Style" are

at times used indiscriminately to the faces imitating the ancient

founts, and to those which are a modern modification of them. It

may, however, be desirable ... to call the one "Old Face" and

the other . . . "Old Style".' And that has been the general

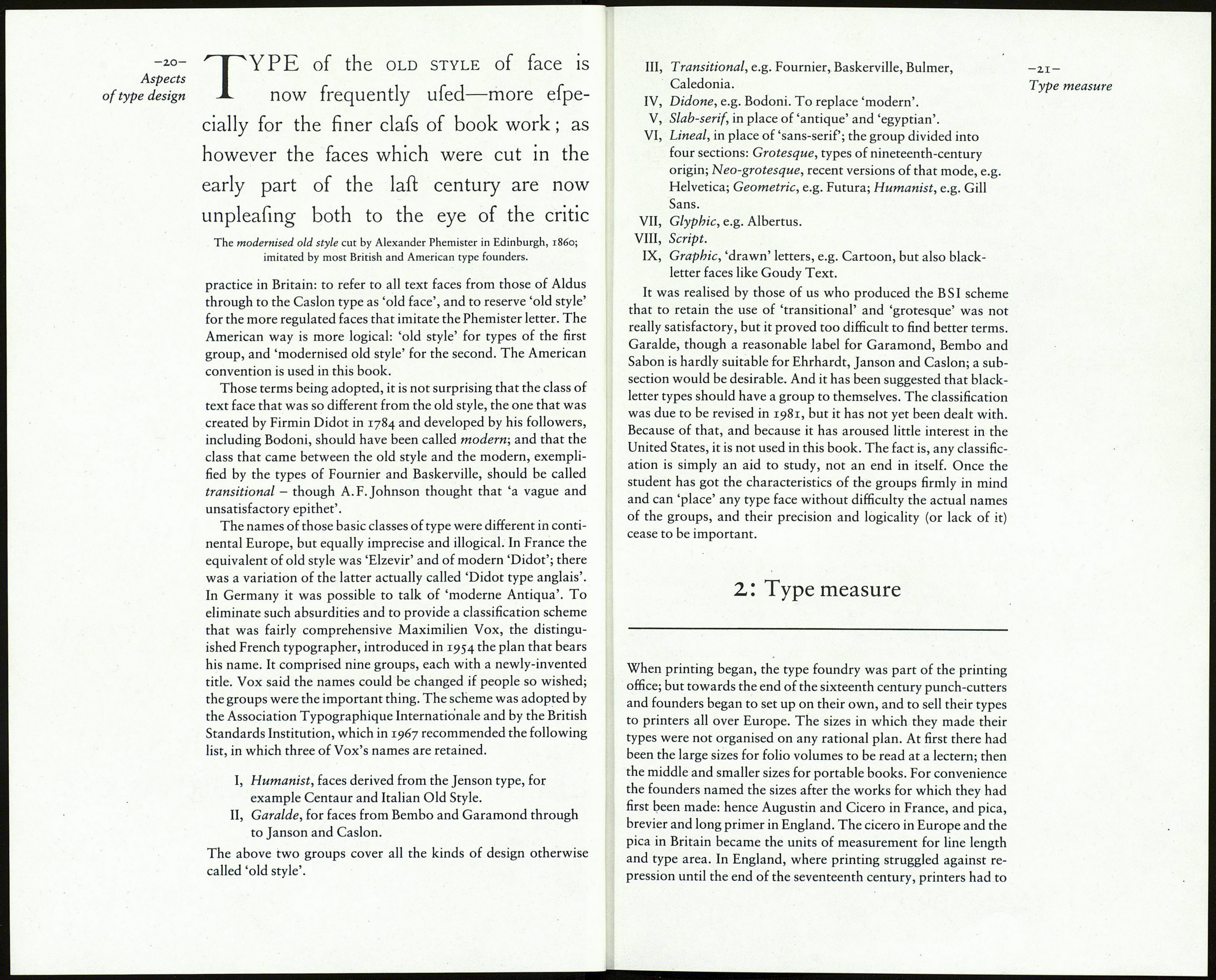

ABCEGHJKMPQRSTW

abcdefghij klmnopqr s tuvwxy z

ABCEGHJKMPQRSTW

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

ABCEGHJKMPQRSTW

abcdefghij klmnopqrstuvwxyz

ABCEGHJKMPQRSTW

abcdefghij klmnop qr stuv wxyz

The three basic styles of seriffed faces.

Old style, represented by Bembo, с. 1495, and Janson, с 1685;

Transitional, Fry's Baskerville, e. 1768;

Modern, Walbaum, с. i8io.