Figure 1

Figure 4

*3-| MAIUSCOLE И*

ABCDEFG

HIJKLMN

OPQRST

ABCDEFG

HIJKLM

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 5

12

1 Roman monumentai capitals. Commemora¬

tive Inscription on black marble, found near St.

Pantaleon in Cologne. (Photograph from the

Römisch-Germanischen Museums, Cologne,

from Albert Карг, Deutsche Schriftkunst.j

2 A page from the Manuale Tipografico by

Giambattista Bodoni. Parma, 1818.

3 A page from Der Wassermann by F.H. Ernst

Schneidler.

4 The letter A in the style of a roman capital.

5 Decorative initial by Johann Neudôrffer the

Elder.

6 Initial by Karlgeorg Hoefer.

INTRODUCTION

Writing serves communication. It does

so direcdy by making language visible,

and indirecdy by relating aesthetic val¬

ues. Every letter and every functional

unit of writing represents a sound of

language and has its own visual value.

Readability is the function of writing; its

visual appearance is the form. The con¬

nection of form and readability consti¬

tutes design. "Good lettering requires

as much skill as good painting or good

sculpture. . . . The designer of letters,

whether he be a sign painter, a graphic

artist or in the service of a type foundry,

participates just as creatively in shaping

the style of his time as the architect or

poet," wrote Jan Tschichold.1 The range

of possibilities in the Western art of

writing reaches from ancient Roman

inscriptions and Bodoni's Manuale Tipo¬

grafico to the designs of Schneidler and

Gaul, where words are mere pretexts for

design opportunities; it includes the

classical letterforms of Trajan's Column

as well as the decorative and playful ini¬

tials of Neudôrffer or Frank, the clear

and somber shapes of the sans serif,

and the alphabet written by Karlgeorg

Hoefer with bold strokes of the brush.

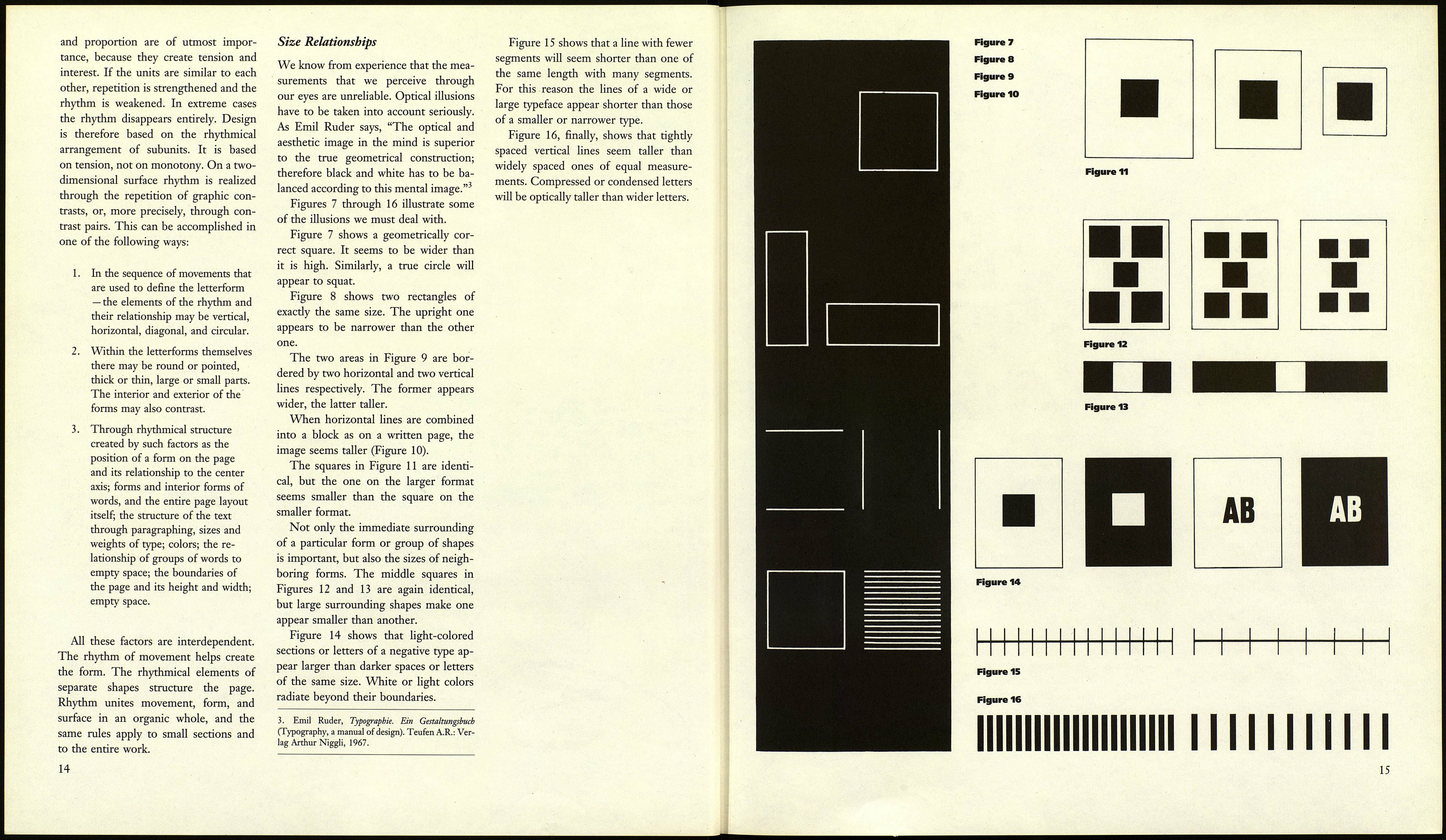

The examples in Figures 1 through 6

and others in Chapter 4 of this book

show that optimal readability is not the

only possible aim of writing. Every spe¬

cific situation, every artistic intention,

requires that form and readability be

balanced against each other. The laws

of formalism exert themselves in the

creation of single letters, in the relation

of letters to each other and in their com¬

bination as a typeface.

These laws can be learned as a "gram-

1. Jan Tschichold, Treasury of Alphabets and Letter¬

ing. Reprint. New York: Design Press, 1992. Copy¬

right © 1952, 1965 by Otto Maier Verlag,

Ravensburg.

mar of design," in Walter Gropius's

words,2 but they are nothing more than

the necessary prerequisites for the vis¬

ualization of creative thought. Creativity

itself is not based on the application of

rules alone. To form and to shape would

remain mere dexterity but never mature

to an art if it were not for the specific

aspects of individual talent, which —if

present—can be developed and guided

but never learned.

BASIC ELEMENTS OF DESIGN

Contrast

Every effect depends on contrasts, which

appear either as pairs or alone. In the

latter case an association is formed in

our minds which completes the contrast

that is assumed to be known.

In design we are always dealing with

contrast pairs. Every measure needs a

countermeasure to activate it. In relation

to writing this means that the design

unfolds on an empty page, the contours

of the letters become visible only against

the background of the white paper. Dark

groups of letters draw their expressive

value from juxtaposition with lighter

ones. Large units look large only in rela¬

tion to small ones, excitement needs

repose, the effect of a color is influenced

critically by adjacent colors.

Rhythm

The second element of design is rhythm.

This may be created by regular repe¬

tition of like units or by repetition of

similar units in opposition. If certain ele¬

ments are stressed above the others,

rhythmical values are increased. Spacing

2. Walter Gropius, Architektur (Architecture). 2nd

ed. Frankfurt/Main, Hamburg: Fischer Bücherei,

1959.