^^^J

Figure 105

H

Figure 106

Figure 107

Figure 108

Figure 109

итпллл

VIVIVIVIV

XIXIXIXIX

I0000I

ssssssss

Lettering with a Round-ended Nib. Before

you start work, it is important to find

the right ratio between stroke width and

letter height. The measurements given

on nibs are not necessarily accurate and

should be checked (Figure 105).

A ratio of one to ten seems best for

first exercises. If you use a pen that

makes lines Vu inch (2 millimeters) wide,

choose a letter height of гА inch (2 centi¬

meters). Next you have to determine

the amount of space between the lines.

Not all the hints given in Chapter 1

will be relevant to the beginner, but it is

advisable to choose a distance of slightly

more than half the letter height (Figure

106) at first. Subsequently one of two

methods can be used: letter groups of

three or four lines each with different

line intervals and choose the spacing that

looks best, or cut out the lines and

rearrange them until the right spacing

is achieved.

Determine your margins on an exer¬

cise sheet and draw guidelines on it (see

The Work Space, page 33, and the sec¬

tion on Documents and Addresses, page

175). Consider the relationship of the

text block to the margins (Figure 108). it

is not necessary to aim for justification —

alignment of the lines at the right margin

— and the lines certainly should never be

squeezed into a block of predetermined

size. An unaligned and somewhat resdess

right margin is usually more pleasing

than letters and spaces that have been

stretched or compressed to fit exactly

into the full measure of the line. Both

the left and the right margin, however,

should carry the same weight optically.

Use the basic form elements of the

capitals as components for ornamental

exercises. This will familiarize you with

your pen, and you can experiment with

distances between the elements. Let

round and pointed shapes protrude

slighdy from the guidelines (see Figure

22). Combine the rows to design areas,

and aim for a dense texture on the page

as well as for even gray values over the

entire area (Figure 109).

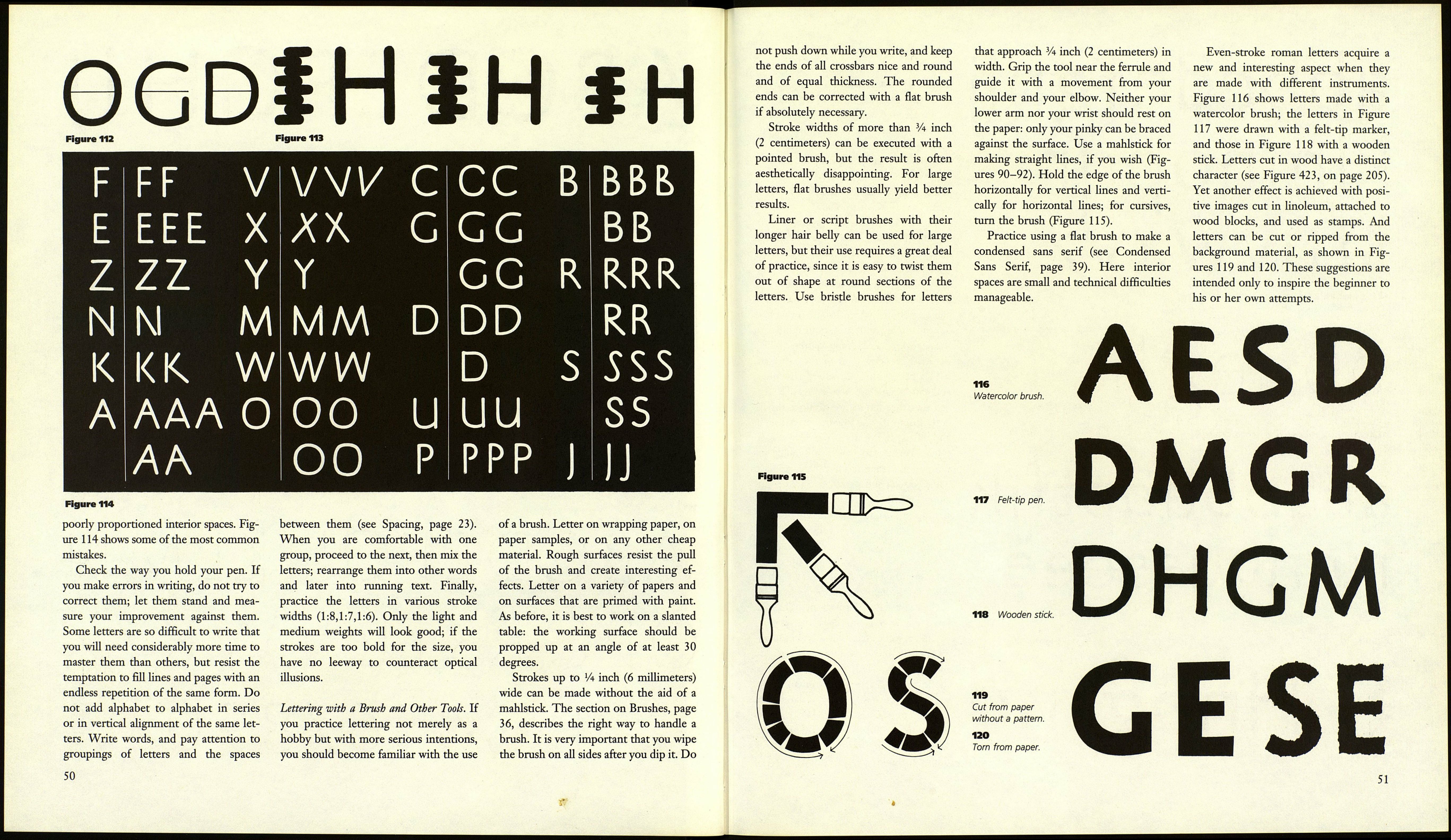

Figure 111 shows the proper direction

of each stroke. To make the learning

process as simple as possible, practice

letters with similar elements as a group.

Start with those that consist only of ver¬

tical and horizontal lines: I, E, F, L, T,

and H. Remember the remarks about

the optical middle of objects in Chapter

1, and place the crossbars accordingly.

The only exception to this rule is the let¬

ter F: its short middle arm can remain in

the geometric middle of the vertical.

Next comes the group of letters that

contain diagonals: A, V, N, Z, M, X, W,

Y, and K. Make little dots at the desired

endpoints of the diagonal lines and con¬

nect them later, but try to write the

letters as unencumbered by such con¬

struction help as possible. Difficulties

usually arise with M and W. The two

outer lines of M are neither exacdy ver¬

tical, nor are they as slanted as the two

outer lines of W. The M is not an in¬

verted W! In the letter W the left-and

right-slanting diagonals should be paral¬

lel to each other. The space inside the Y

is frequently too small; make it slightly

larger than the space enclosed by the

upper portion of X.

The third group consists of letters

that are roughly a circle in form: O, Q,

C, G, and D. None of these letters

forms a perfect circle; the upper halves

appear larger (Figure 112).

The last group is made up of В, P, R,

J, U, and S. The crossbar of the В lies in

the optical middle; the interior spaces of

R and P should be larger than those of

B, which brings the crossbars of R and

P into the geometric middle.

Keep comparing your letters to mod¬

els or established proportions. Faulty

designs usually attract attention through

48

ABCDEFCHIJ

KLMNOPQ

RSTUVWXYZ

1234567890

110 Sans serif even-stroke roman.

111 Stroke directions.

ABCDEFGHKLMN

OPQRSTUVWXYZ

1234567890