о

о

Figure 17

Color

In lettering color only serves and sup¬

ports the aim of readability: it attracts

attention and creates associations. A

basic knowledge of color theory has to

be assumed. A good text on the topic is

recommended for further reference.

Light/Dark Contrast

Optical illusions have to be taken into

account in relating different sizes to each

other; a similar situation exists in color

design. The values perceived by our eyes

are rarely identical to the actual color

values. Adjacent colors and light condi¬

tions influence our perception. Disre¬

garding the strongest light/dark contrast

that exists, between black and white,

every hue of the color wheel has its own

lightness or value, the lightest for yel¬

low, the darkest for blue. Red and green

have equal values. In addition, every

color can be represented in lighter or

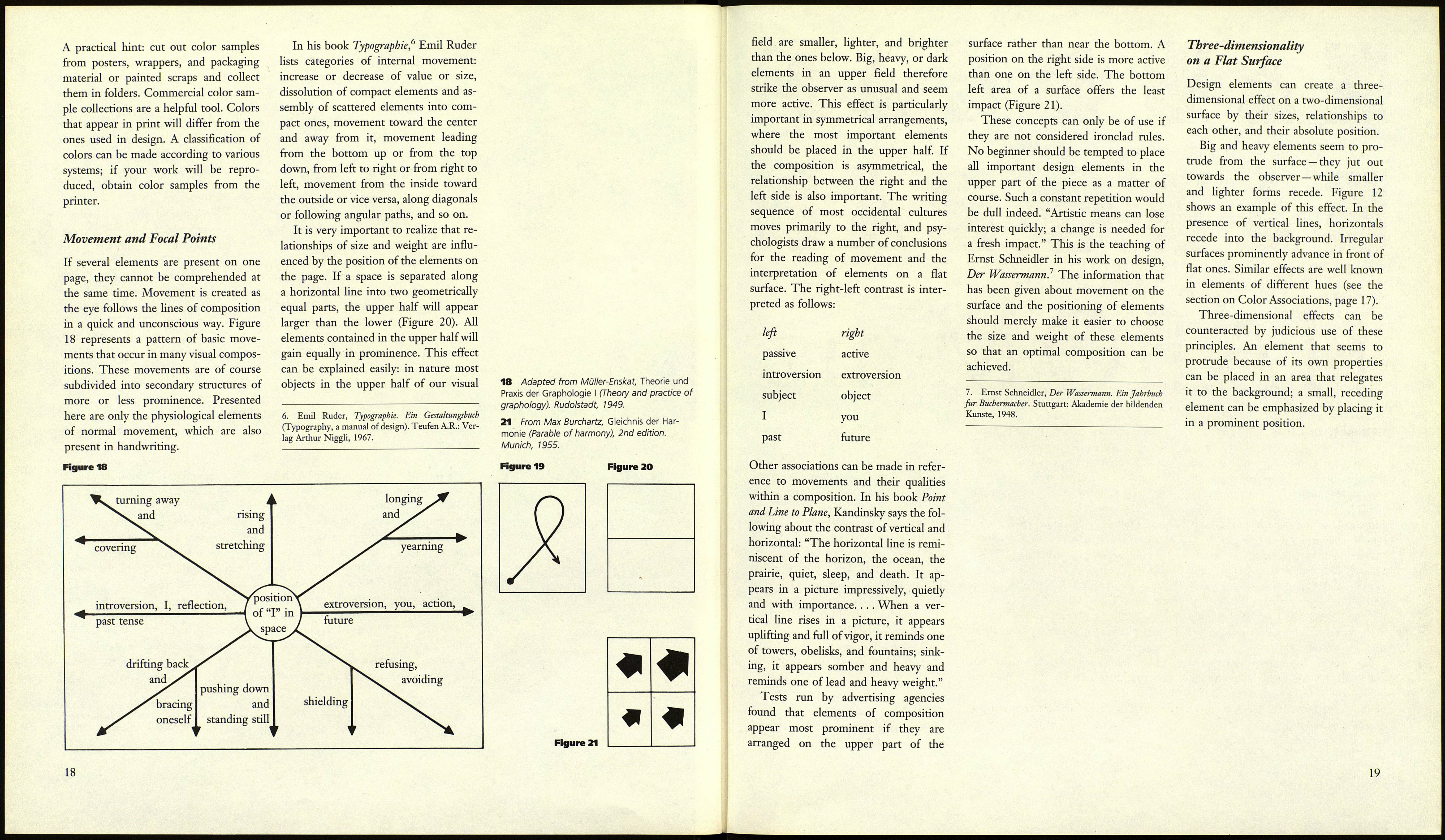

darker shades. As seen in Figure 17,

these gradations of value are of great

importance for the relationship of letter¬

ing and background, since the legibility

of the writing depends on them. The

greatest contrast can be seen in fields la

and 3e.

A pure white surface may be too

harsh for the design of books, since its

radiance causes the contours of the let¬

ters to appear fuzzy, and clarity is dimin¬

ished. It is common, therefore, to use

white paper with a slight warm tint for

commercial applications. To prepare a

wall for lettering, white paint should be

mixed with some ocher or brown. Black

can also be softened through the addi¬

tion of brown.

In comparing the fields lb, c, d and

3b, c, d in Figure 17, we can observe that

the white circles seem more detached

from the background than the black

ones. This happens because white is a

more active color than black and out¬

shines the other colors. Thus, on col¬

ored backgrounds of medium darkness

white lettering appears more clearly

than black lettering. In row 1 the circle

in field e seems even more prominent

than those in fields b, c, and d because

of its white contour. In row 2 it can be

observed that the same gray circle

appears darker on white, and lighter on

black. Similar effects result when gray

16

circles are put on intensely colored back¬

grounds. The gray will shift towards the

complementary color of the background

— that is, it appears greenish on red,

yellowish on blue. Another setup in¬

volves primary colors. If the gray circles

are replaced by red ones on blue and

yellow backgrounds, the red circle on

the yellow will appear darker than the

red circle on the blue, because it takes

on some of the complementary color of

yellow. This phenomenon is known as

simultaneous contrast. The exception

to it occurs when two complementary

colors of the color wheel in their full

strength are opposed. In this case both

colors would appear enhanced. For opti¬

mal readability and visibility over greater

distances the light/dark contrast of

lettering and background is of utmost

importance. A red and a green of equal

value can cancel each other out visually

and produce a flickering image.

Warm/Cool Contrast

No actual feelings of warmth and cold¬

ness are connected to colors. The words

"warm" and "cool" represent "an asso¬

ciation that the colors elicit in our

minds."4 The strongest warm/cool con¬

trast exists between a yellowish red and

a greenish blue. On the color wheel the

warm colors are located between yellow

and red, the cool ones between blue and

green. The colors between red and blue

are simultaneously warm and cool, the

ones between yellow and green are

neither warm nor cool. Warm colors

seem active, attract attention, and ad¬

vance from the surface; cool ones seem

passive and recede into the surface.

4. Paul Renner, Ordnung und Harmonie der Farben

(Order and harmony of colors). Ravensburg: Otto

Maier Verlag, 1947.

Pure and "Broken" Colors

Every color loses some of its brightness

when it is dulled or "broken" by the ad¬

dition of gray, or, more effectively, by

the addition of some of its complemen¬

tary color. Pure colors appear prominent

opposed to broken ones; the intensity of

a pure color can be heightened consider¬

ably by juxtaposition with broken colors.

Color Associations

Colors have psychological and symbolic

value, though associations vary depend¬

ing on culture or even point of view. For

example, the color green may conjure up

the image of immaturity or, alterna¬

tively, environmental concerns. In some

cultures white is associated with mourn¬

ing, whereas in the West we generally

think of it as pure, festive, cheerful,

and noble. During the Middle Ages in

Germany green, not red, was the color

of love. These are just a few examples of

different color associations. The associa¬

tions also depend on whether the colors

are light or dark, warm or cool, pure or

broken, and are heavily influenced by

what Albert Kapr calls "conditions of

landscape, nationality, history, religion,

and class."5 Tradition and custom per¬

petuate them.

Colors also depend on the light under

which they are seen. At dusk red appears

darker, blue lighter. Artificial light alters

almost all colors, and influences blue

and green most strongly.

There are no recipes for good color

combinations. Taste can be cultivated

through the study of works of classical

and modern painting or graphic art.

Abstract works are particularly useful.

5. Albert Kapr, "Probleme der typografischen

Kommunikation" (Problems in typographic commu¬

nication), in Beiträge zur Grafik und Buchgestaltimg.

Leipzig: Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst,

1964.

17