with the facade. Lettering should not

overpower architecture — it is usually

much too large.

In choosing materials and techniques,

take into consideration the lighting con¬

ditions both day and night, the way in

which the lettering will be secured on

the structure, requirements of durability,

and last but not least the colors and tex¬

tures of the background and the sur¬

rounding areas. When choosing a letter

style, remember that on modern struc¬

tures we often find a constructed sans

serif. The effect of this style of lettering

parallels a functional puritanism in mod¬

ern architectural design. Basic attitudes

in architecture have been changing, but

have not yet influenced lettering and its

application. But those style problems

aside, roman types such as Garamond,

Bodoni, or Walbaum and historical sans

serifs or Egyptians are often much better

suited to modern building styles because

they enliven the glass, aluminum, and

concrete surfaces in a most appealing

way.

It is more difficult to choose the right

lettering style for a historic building.

Proceed with great care. The letters

must be compatible with the era. Neon

signs have no place on architecture that

predates electricity. The eclectic styles

of the latter half of the nineteenth cen¬

tury pose special problems. Here, keep

neon signs small to avoid stylistic con¬

tradictions, and consider the variations

of classic typefaces that were developed

at the beginning of the nineteenth cen¬

tury and the beautiful and detailed rich

Egyptians and sans serifs from the same

period.

Whatever the style you select, it must

lend itself to the method and materials

that you want to use. Not every lettering

style can be adapted. Handwritten mod¬

els are particularly sensitive. Neon signs

could represent handwriting, as long as

the letters are mounted on a flat surface

and not on three-dimensional forms.

Three-dimensional lettering should not

be used if the viewers' vantage point will

be low, since the perspective may distort

the forms. Problems can arise if an al¬

ready existing logo has to be incorpo¬

rated into the design; that is why it is

best to plan such applications when you

design a logo.

A good relationship with the architect

and the workmen is essential for success

in a construction job. It is imperative to

obtain all relevant technical information

before the designing process can begin.

Make a sketch of all the characters in

the right proportions. Get a photograph

of the building you are working on, and

make a model in cardboard, if necessary.

Use the actual colors, if you can, and

check them on location. It might even

be possible to project a slide of your de¬

sign onto the appropriate area of the

building at night to get an impression of

the final effect.

Practical Hints

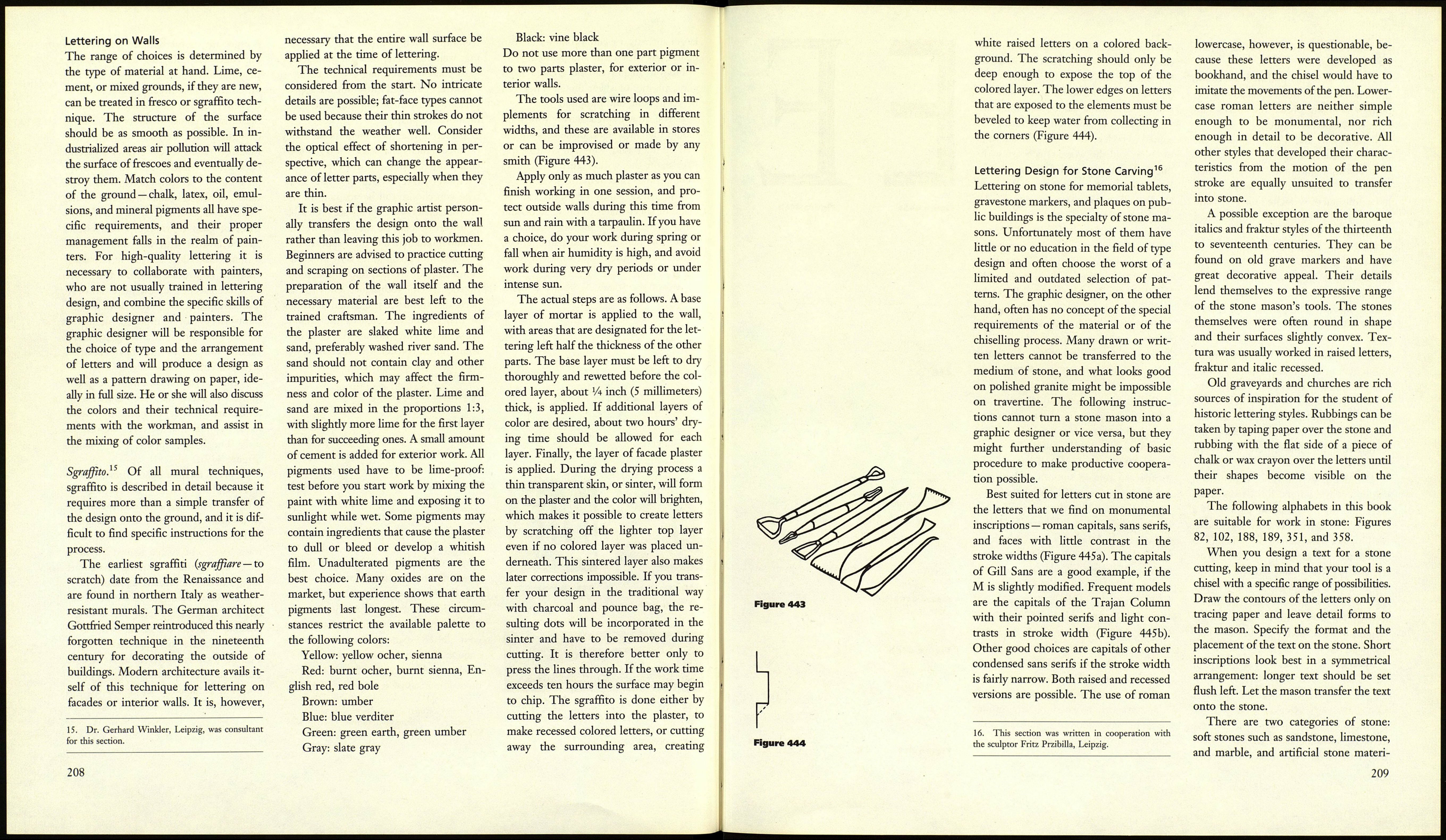

Letters can be scratched in plastered

walls (sgraffito), painted, set in mosaic,

or constructed in various materials and

applied. Match backgrounds of ceramic

or natural or artificial stone with letters

of the same material. The lettering can

consist of single letters that are flat or

three-dimensional, or of completed signs

that are attached to the wall.

Material for single letters can be metal

that is treated in various ways (plated,

gilded, chromed, enameled). Letters

with serifs are usually cast or punched. If

every letter is produced individually, it

can be cut from sheet metal or from

metal rods, formed, mounted, and as¬

sembled. Welding is another possibility.

Plastic materials can be poured into

forms, reinforced with glass fibers for

и

Figure 436

О

о о

ö

1

о ПО

о

п

Figure 437

О

о

L°J

Figure 438

У

ft

гт

ft

Figure 439

206

larger formats, or cut. Wood letters can

be cut out with a saw and painted.

Hollow shapes can be created from

glass, plastic, or sheet metal. They can

be sawn, bent, and mounted.

If you attach single letters to a wall,

mount them at a slight distance from the

wall so that rain will not create dirty

streaks on the wall. Figure 436 shows

some profiles of relief letters.13

The backgrounds for signs can be

made of sheet metal (bronze, steel, and

other metals), glass, plastic, wood, and

stone. On metal you can paint letters,

punch or saw them out, or use a relief

13. From Walter Schenk, Die Schriften des Malers.

Giessen: Fachbuchverlag Dr. Pfannenberg, 1958.

440 Daytime. 441 Nighttime.

442 This is an interesting idea, but unfortu¬

nately the details of the lowercase letterforms

cause light spots. Capital letters might have

made a better solution.

technique, such as bronze casting, etch¬

ing, welding, inlay, or even gluing. On

glass you can paint, engrave, or etch.

Letters chiselled into stone are appro¬

priate for historical buildings and com¬

memorative plaques.

Concrete is a good medium for relief

or three-dimensional work—it is not used

nearly often enough in this capacity.

Always make certain that the letter

type you choose can be adapted for use

on your materials. Capitals are preferable

to lowercase because they are more sta¬

tic and monumental in their appearance.

The list of possibilities is by no means

complete, nor are the following descrip¬

tions of specific techniques. Only the as¬

pects that influence the design decisions

or that can be executed by the graphic

artist alone are discussed. Whatever

your choice, consult with specialists be¬

fore the work commences.

Special Techniques

Neon Signs

Neon lettering poses special problems

because it has to remain visible day and

night, and the character of the letters

should not change under different light

conditions, especially if a logo is in¬

volved. If the tubes are attached to raised

letters, their surface should not be too

striking. Consider the color and the in¬

tensity of the light as well as all design

elements in the immediate surround¬

ings. You can mount the tubes on three-

dimensional letters or directly on a col¬

ored background, but in the latter case

your letter spacing must be ample

enough to avoid blurring. Figure 437

shows possible arrangements of tubes on

three-dimensional letters.14 Variation 2

14. From Gottfried Prolss, Schriften für Architekten

(Lettering for architects). Stuttgart: Verlag Karl

Kramer, 1957.

is especially useful, because the protrud¬

ing edges keep blurring to a minimum.

In variations 4 and 5 the surface of the

raised letter is indirectly illuminated, so

the letters appear as silhouettes. None of

these five versions looks its best during

daylight hours, because mounting the

tubes on raised letters creates a certain

restlessness. Aesthetically much more

pleasing are constructions where the

tubes are placed inside three-dimensional

letters and covered by a translucent

sheet of glass or acrylic. Good effects

can be created with side walls of con¬

trasting color. Since acrylic can be shaped

easily, it is possible to make the entire

structure except the base plate out of it.

Three-dimensional letters with diffuse

light effects can be mounted on a wall

or recessed into it totally or partially.

Figure 438 shows the most common

arrangements.

A third variation is to light the letters

indirectly. Here the three-dimensional

letters are open at the back and illumi¬

nated by tubes that are recessed into the

wall. The letters appear as silhouettes

(Figure 439).

A special form of either direct or indi¬

rect lighting consists of rectangular,

oval, or round shapes which totally en¬

close each transparent letter (Figures

440 and 441). Signs that are mounted on

roofs have to be visible against bright or

dark skies; the mounting hardware

should be as unobtrusive as possible.

Technical requirements for neon let¬

ters can be quite complex, and it is im¬

possible to comment on all of them in

detail. Problems with materials can stall

a project completely, so it is wise to

gather all relevant information from ap¬

propriate companies before any designs

are chosen.

207