Comme quelqu'un pourrait dire de moi que

j'ai seulement fait ici un amas de fleurs étrangères,

n'y ayant fourni du mien que le filet à les lier.

Montaigne. Essais, m.xii

The next step in the study of type is to learn

to recognize the various forms or 'tribes' of type

and the subtle differentiations between varieties

of the same general form of type-face.These

differences are very slight; often to the casual

observer no differences appear. There is no way

to learn to recognize them except by training

ЛееУе" D.B.Updike

Printing Types, Their History, Forms, and Use, 1937

Of every class of type there are many forms, but

one or two forms only that are the best.We can

learn what these best forms are by knowing what

early handwriting and early type was, and what early

printers meant to do. Only when we understand

their problem can we justly judge how well they

solved it.To see what the manuscripts were that

they tried to reproduce in type is a step to this

knowledge ; to see how forms produced by a pen

were changed when rendered in metal is another.

A third step is the realization of the influence of

history, nationality, scholarship, and custom upon

type-forms. We must also have a comprehension of

the evolution of economic problems—how cheaper

books were demanded, how that want was met,

and what its effect was on types and their use.The

ability to recognize all this can be arrived at only

by that historical perspective and that training of

the eye which is gained by study and observation.

ibid.

But any one may arrive at sound conclusions as

to types, if he knows thoroughly the history of

type-forms, has an eye sensitive to their variations,

and has familiarized himself with the ways in which

they have been employed by masters of typography.

ibid.

xii

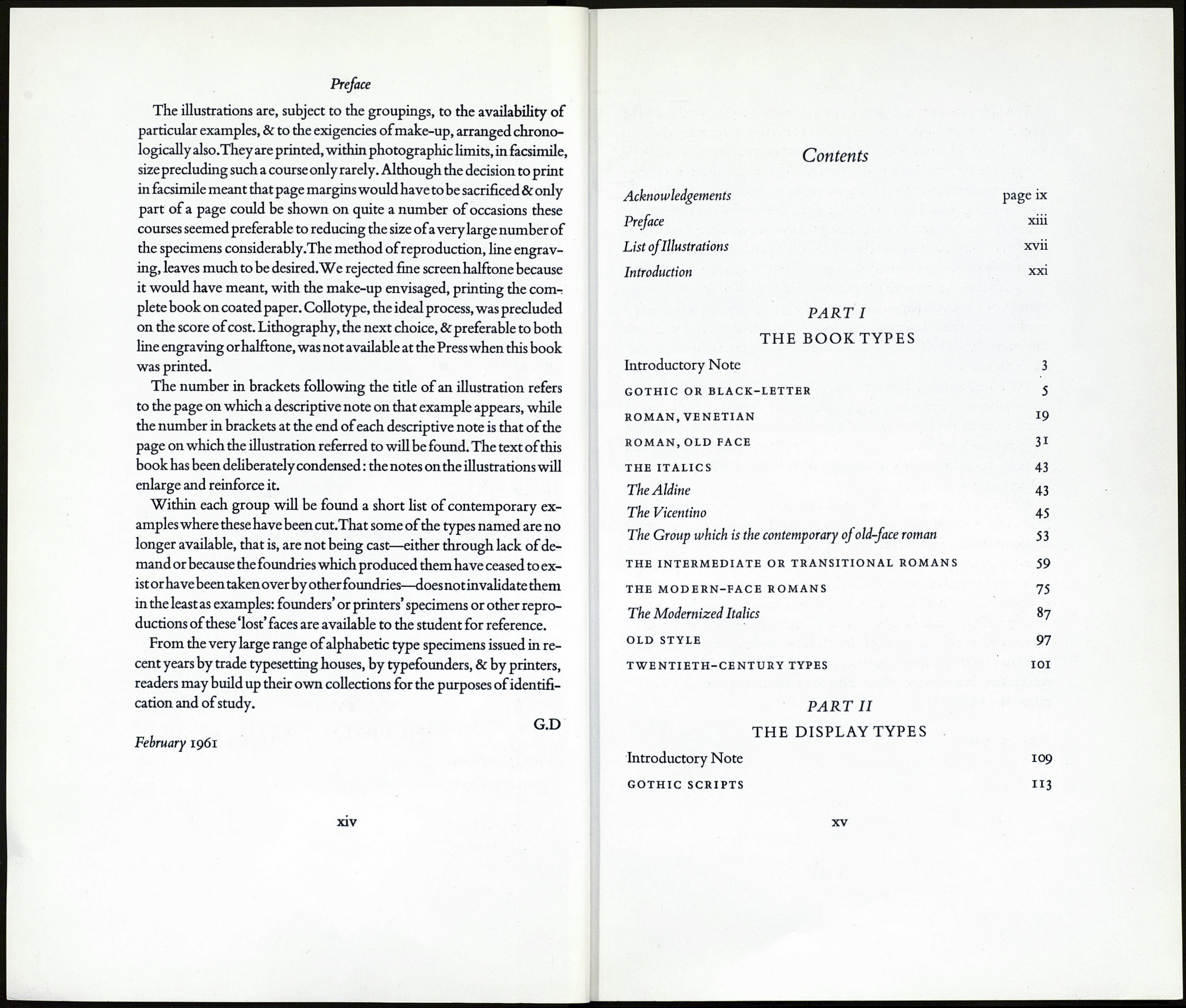

Preface

This book is intended simply as an introduction to a subject which has

already been well documented byD.B.Updike, A. F.Johnson, Stanley

Morison, Paul Beaujon, Harry Carter, James Wardrop and others. It

has been written to help those students who have not as yet had an op¬

portunity to study the work of these authors with any thoroughness,

if indeed at all: or, having both opportunity and inclination, yet feel

dismayed at the immensity of the subject—covering as it does so many

countries and compassing a period of over five hundred years. From

that point it may only be a short step to questioning the need to delve

into the history of printing types at all : to regard it as a field remote from

present day needs & the task of earning a living, in fact, one best left to

scholars—to the historians of printed books and ephemera—some of

whom they realize may already have devoted a lifetime to such research.

Yet without some knowledge of the history of type faces—of the his¬

torical, personal, economic, industrial, & other factors which determin¬

ed the development of types in certain ways at certain times—& without

some familiarity with the ways in which the great printer-publishers

of the past have used those types, we cannot hope to be able to identify

type faces, to choose them intelligently, to mix them with assurance, or

to produce with them work having that quality of inevitability which

the late Mr Bruce Rogers said always marked successful typography.

In this Introduction types have been grouped and the groups appear in

chronological order. Each group of faces is prefaced with a brief histor¬

ical note, the material for which in most instances I am entirely indebted

to the historians cited above. Following these historical notes, and con¬

fined to the book faces, are notes on the characteristics of the types in

the particular groups, written in the hope that they will help to facili¬

tate the identification of individual specimens. For these analyses I am

especially indebted to Mr A. F.Johnson of the Department of Printed

Books, British Museum,and also to Mr W.Turner Berry, until recently

Librarian of the St Bride Foundation Printing Library.

хш