36

Art in the Alphabet.

ends. Historically, we arrive at that in Lombardie

and other writing as early as the 8th century (60).

Anticipating this dilation, the penman eventually

made strokes in which the elementary straight line

altogether disappears (68). Further elaborating,

he arrived at the rather sudden swelling of the

curved back of the letter, familiar in work of the

13th century and later (73, 87). With the forking

of the terminations, and the breaking of the out¬

line in various ways (20), we arrive at fantastic

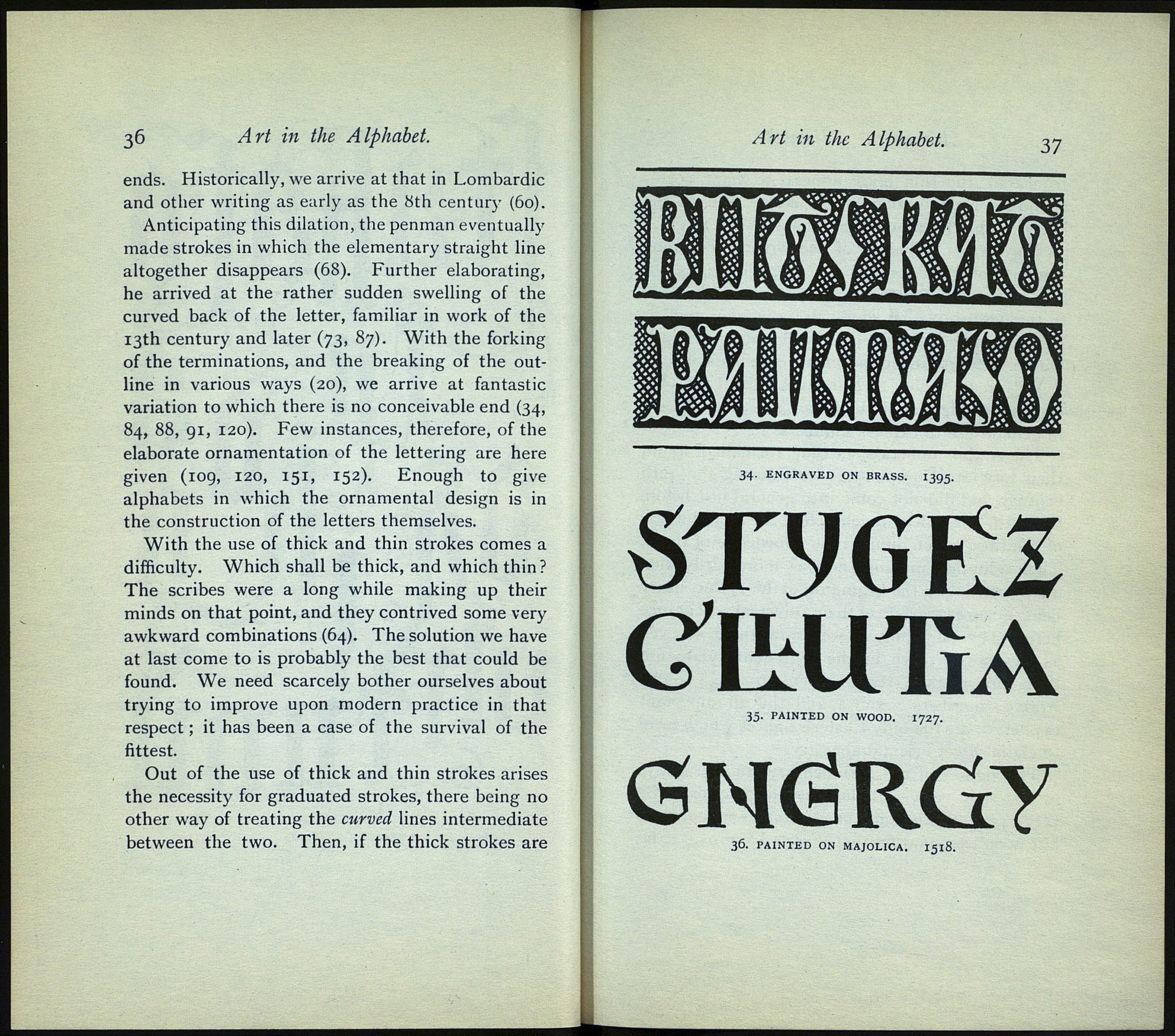

variation to which there is no conceivable end (34,

84, 88, 91, 120). Few instances, therefore, of the

elaborate ornamentation of the lettering are here

given (109, 120, 151, 152). Enough to give

alphabets in which the ornamental design is in

the construction of the letters themselves.

With the use of thick and thin strokes comes a

difficulty. Which shall be thick, and which thin?

The scribes were a long while making up their

minds on that point, and they contrived some very

awkward combinations (64). The solution we have

at last come to is probably the best that could be

found. We need scarcely bother ourselves about

trying to improve upon modern practice in that

respect ; it has been a case of the survival of the

fittest.

Out of the use of thick and thin strokes arises

the necessity for graduated strokes, there being no

other way of treating the curved lines intermediate

between the two. Then, if the thick strokes are

Art in the Alphabet.

34. ENGRAVED ON BRASS. I395

STyGEZ

СІШТ1А

35. PAINTED ON WOOD. 1727.

GNtìRCiy

36. PAINTED ON MAJOLICA. I518.