2б Art in the Alphabet.

abrurfgiu

Mmnoçijr?

fstuûnifii

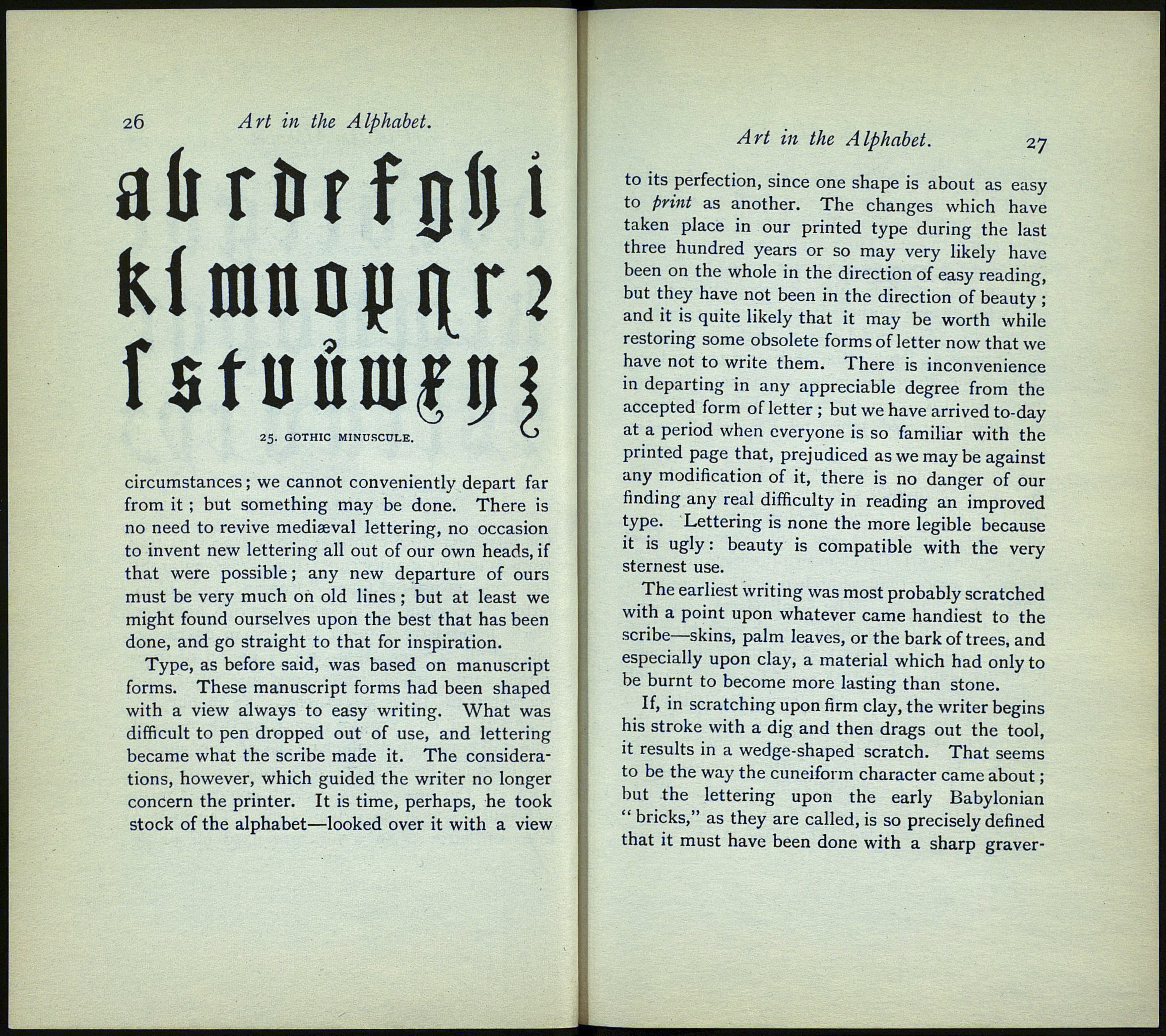

25. GOTHIC MINUSCULE.

circumstances ; we cannot conveniently depart far

from it ; but something may be done. There is

no need to revive mediaeval lettering, no occasion

to invent new lettering all out of our own heads, if

that were possible ; any new departure of ours

must be very much on old lines ; but at least we

might found ourselves upon the best that has been

done, and go straight to that for inspiration.

Type, as before said, was based on manuscript

forms. These manuscript forms had been shaped

with a view always to easy writing. What was

difficult to pen dropped out of use, and lettering

became what the scribe made it. The considera¬

tions, however, which guided the writer no longer

concern the printer. It is time, perhaps, he took

stock of the alphabet—looked over it with a view

Art in the Alphabet. 27

to its perfection, since one shape is about as easy

to print as another. The changes which have

taken place in our printed type during the last

three hundred years or so may very likely have

been on the whole in the direction of easy reading,

but they have not been in the direction of beauty ;

and it is quite likely that it may be worth while

restoring some obsolete forms of letter now that we

have not to write them. There is inconvenience

in departing in any appreciable degree from the

accepted form of letter; but we have arrived to-day

at a period when everyone is so familiar with the

printed page that, prejudiced as we may be against

any modification of it, there is no danger of our

finding any real difficulty in reading an improved

type. Lettering is none the more legible because

it is ugly: beauty is compatible with the very

sternest use.

The earliest writing was most probably scratched

with a point upon whatever came handiest to the

scribe—skins, palm leaves, or the bark of trees, and

especially upon clay, a material which had only to

be burnt to become more lasting than stone.

If, in scratching upon firm clay, the writer begins

his stroke with a dig and then drags out the tool,

it results in a wedge-shaped scratch. That seems

to be the way the cuneiform character came about ;

but the lettering upon the early Babylonian

" bricks," as they are called, is so precisely defined

that it must have been done with a sharp graver-